Om ikoner

Ordet ikon kommer ifrån det grekiska ordet för bild och avbild eikōʹn. Ikoner behöver inte bara vara målade bilder på trä utan kan också skapas i textil, mosaik, elfenben, metall och sten.

Bilden uppfattas inte bara som illustrationer ur Bibeln och andra texter utan som en del av det heliga budskapet. Framställningen betraktas i sig som en helig akt.

Men dess historia har inte varit helt enkel, under den så kallade bildstriden (730–843) debatterades det friskt ifall den ortodoxa kyrkan skulle tillåta avbildningar eller inte. År 843 vann bildvännerna (ikonodulerna) och ikonen blev en självklar och nödvändig del i den ortodoxa kyrkans liv.

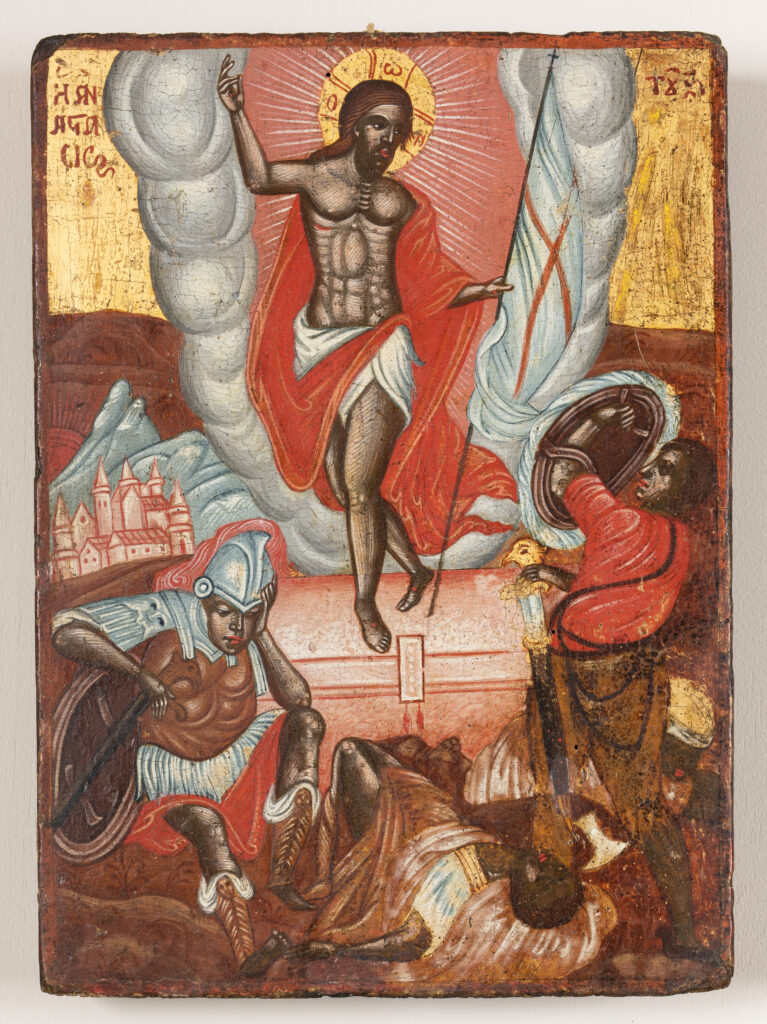

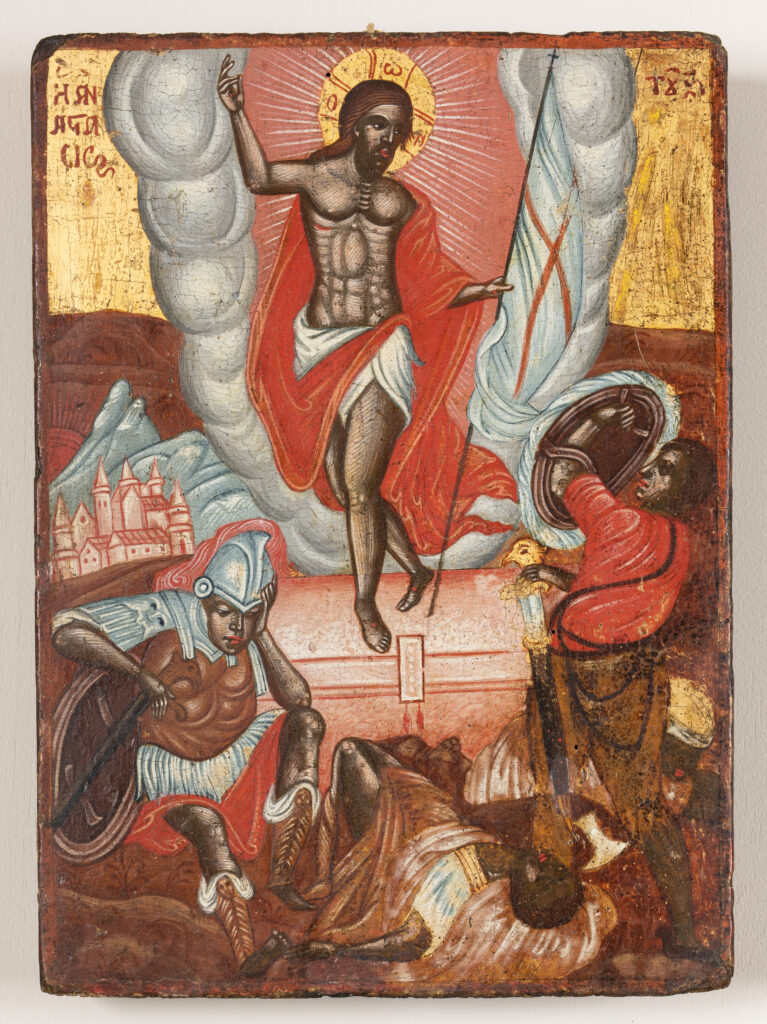

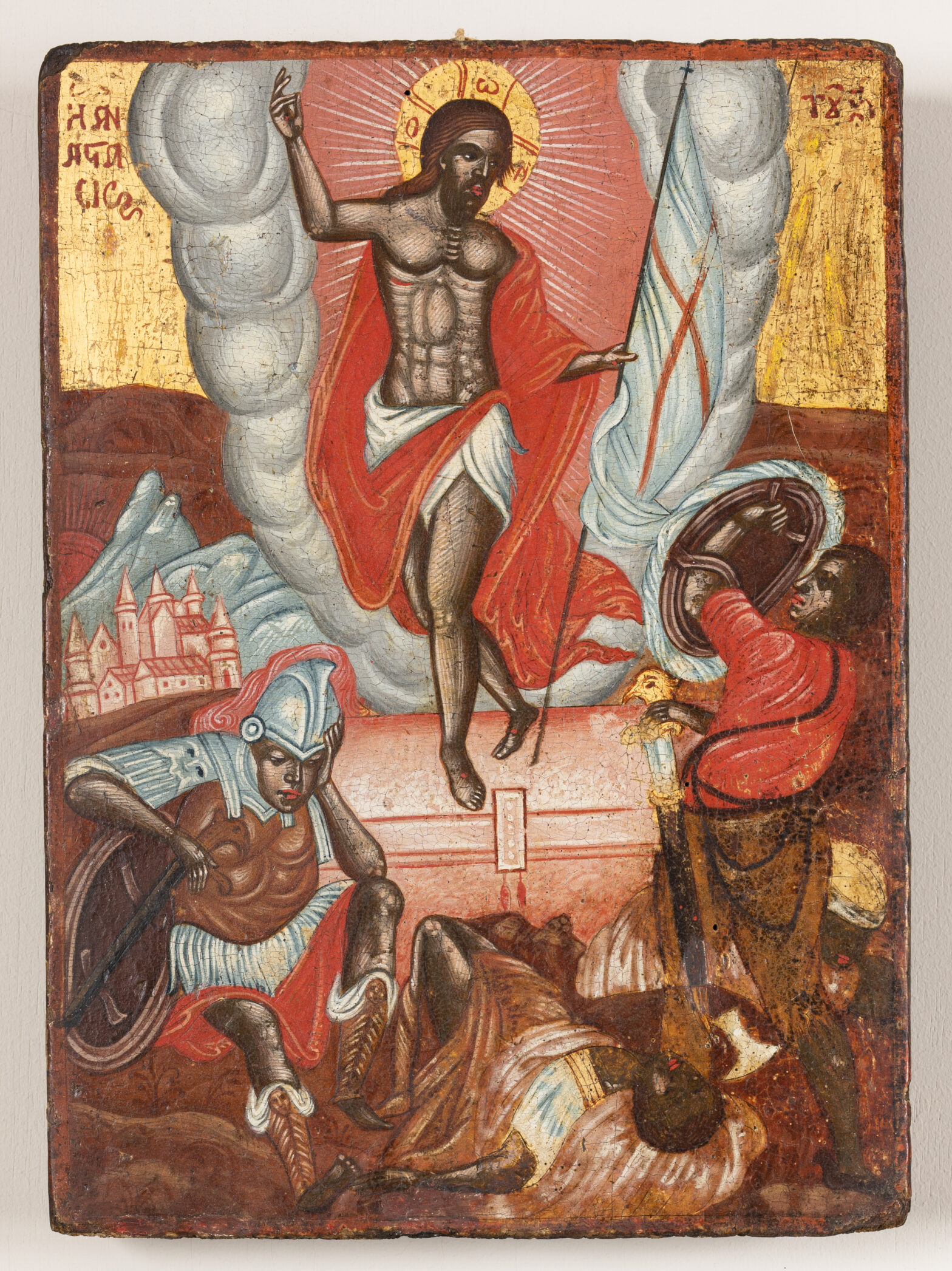

Jesus uppståndelse

Konstnär Okänd

Datering 1700-tal

Material/Teknik Tempera och bladguld på pannå

Inventarienummer. MM8734

Förvärv Gåva 1924

Bilden föreställer en man med gloria, Jesus, ståendes på en stenkista, en grav. Tre män är samlade nedanför honom. I bakgrunden syns berg och en stad.

Vad är en ikon?

Ikoner är heliga bilder i den ortodoxa kyrkan. Ikoner är vanliga i både den grekisk och rysk-ortodoxa kyrkan. De är en viktig del i kyrkans utsmyckning, ikonostasen, men kan också ta plats i människors hem.

Den här ikonen föreställer Jesus återuppståndelse som är en del i den viktigaste högtiden i ortodox tradition, påsken. Gudstjänsten på påsknatten brukar klassas som kyrkoårets höjdpunkt.

St. Onuphrius

Konstnär Okänd

Datering 1600-tal

Material/Teknik Bladguld och tempera på pannå

Inventarienummer MM8732

Förvärv Gåva 1924

Bilden visar en man med långt skägg. Han håller en stav och textrulle i händerna, där han står framför ett landskap med tre höga berg, träd och kullar.

St. Onuphrius räknas till en av ökenfäderna, den första generationen kristna asketer som levde som eremiter och vars levnadssätt inspirerade till klosterlivet. Onuphrius (ibland även kallad Onofrios) tros ha levt och varit verksam på 300-talet.

Biskopshelgon

Konstnär Okänd

Datering 1700-tal

Material/Teknik Bladguld och tempera på pannå

Inventarienummer MM8736

Förvärv Gåva 1924

Bilden föreställer en man, klädd i röd och vit klädsel utsmyckad med kors. Han sitter ned och i ena handen håller han en röd bok, med den andra tecknar han välsignelse.

Varför har så få av ikonerna kända konstnärer?

Alla ikonerna som visas på väggen är skapade av för oss idag okända konstnärer, men hur kommer det sig? Ikonmåleriet har traditionellt utförts i kloster, där själva måleriet är en helig akt med regler och tillvägagångssätt. Ikonframställning har uppfattats som ett heligt uppdrag eller handling. Motiven har varit det centrala och de har oftast reproducerats om och om igen. Därför har det inte varit viktigt att signera de enskilda verken.

Särskilt fram till 1500-talet är ikoner osignerade och flertalet av konstnärerna okända till namnet. I rysk tradition gäller detta även senare.

Helige Elias

Den helige Elias ansågs i rysk folktradition vara härskare över alla naturkrafter, speciellt åska och regn vilket var extra viktigt för bönderna.

Konstnär Okänd

Datering 1600-tal

Material/Teknik Tempera på pannå

Inventarienummer MMK5081

Förvärv Gåva 1980

Ikonen utgörs av 18 mindre bilder som ramar in en större bild i mitten. Motivet föreställer en man, klädd i en pälskantad mantel som tittar upp mot en liten fågel som ses till vänster om honom. De mindre bilderna föreställer människor och händelser ur helgonets liv. Den här ikonen är väggens största ikon (113 cm x 89 cm).

Ikonen består av tre sammanfogade, grova träpannåer. Elias är centralt placerad med 18 mindre rutor. Ikonen läses från övre vänstra hörnet och nedåt, och i bilderna får vi följa scener ur hans liv och gärningar. I det högra hörnet ser vi till exempel Elias släppa ner sin mantel till jorden under sin resa mot himlen.

Ikonen är målad av Novgorodskolan som var en av de mest betydelsefulla skolorna för ikonmåleri. Här utvecklades en mycket uttrycksfull stil och en viktig del var den röda färgen som vi ser här. Den röda färgen kunde ersätta traditionell förgyllning och användes både av ekonomiska skäl och för att den står ut samt ”lockar ögat”.

Ärkeängeln Gabriel

Konstnär Okänd

Datering 1500- 1600-tal

Material/Teknik Trä, mässing, äggtempera på kredering

Inventarienummer MMK 5828

Förvärv Inköp 1988

Bilden visar ett huvud där ansiktet tittar åt vänster. Ängeln som är avbildad har lockigt hår, och en gloria bakom sig.

Ärkeängeln Gabriel återfinns inom alla abrahamitiska religionerna (kristendom, judendom och islam). Gabriel anses inom kristendomen vara den främsta av ärkeänglarna och förekommer som Guds sändebud på flera ställen i Bibeln.

Gabriel avbildas oftast i bebådelsescener inom konsten då det var han som i Lukasevangeliet sänds till Maria för att berätta att hon ska föda en son.

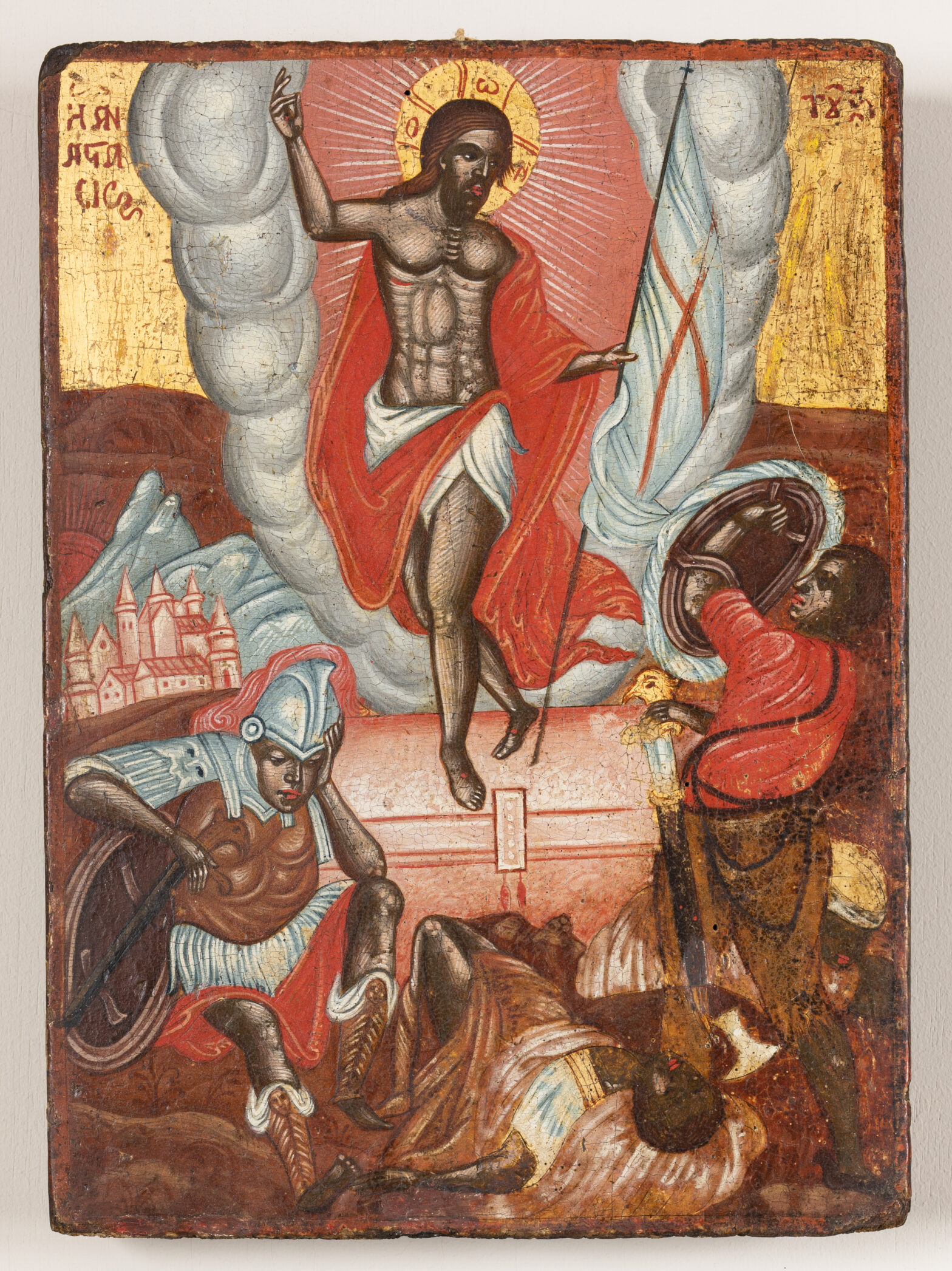

St. Paraskeva

Konstnär Okänd

Datering 1700-tal

Material/Teknik Pannå

Inventarienummer MMK 8229

Förvärv Gåva 2000

Bilden föreställer en kvinna, iklädd en mantel och med en gloria runt huvudet.

Paraskeva kallas också Paraskevi vilket betyder fredag på grekiska. Inom ikonmåleriet återkommer därför helgonet med namnet Den heliga fredagen. Paraskeva avbildas ofta som en personifiering av Kristus lidande på Långfredagen, och är därför inte att betrakta som en historisk person. Samtidigt har det uppkommit berättelser om att hon har en speciell roll för handelsvärlden, och att hennes närvaro var viktig vid torghandel och marknader.

I ikonen som visas i utställningen håller Paraskeva ett martyrkors i sin högra hand och i den vänstra ett språkband. En liknande Paraskeva-ikon finns på Nationalmuseum i Stockholm och jämför vi dem blir det extra tydligt hur lika ikonerna är i sin komposition.

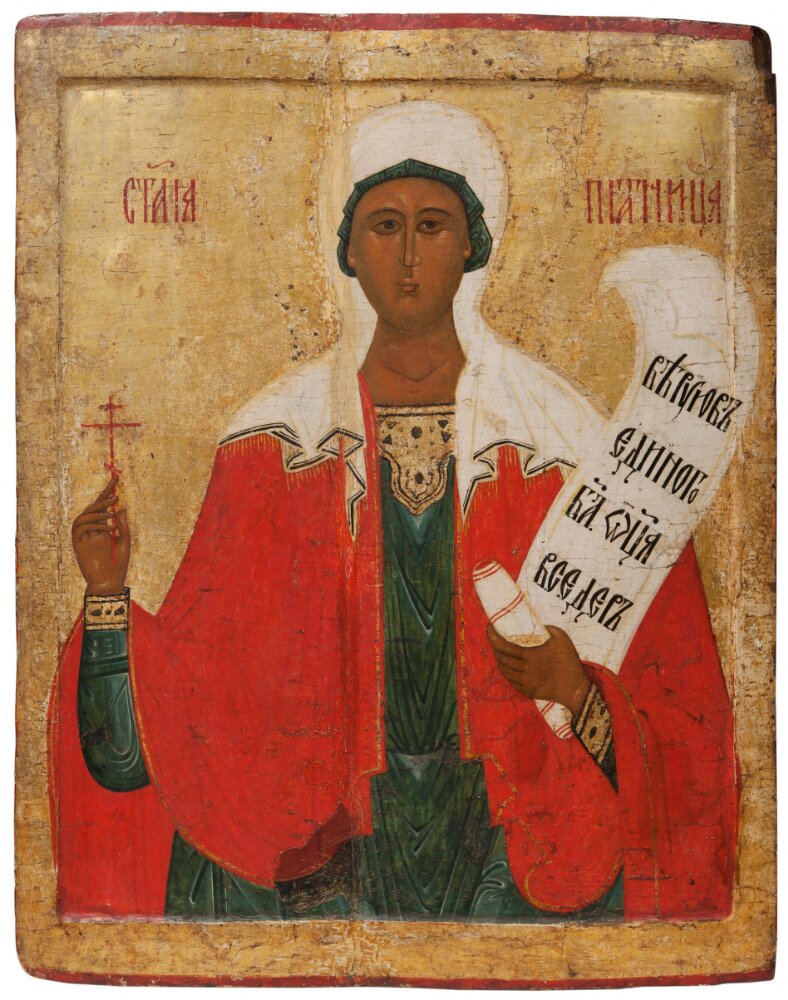

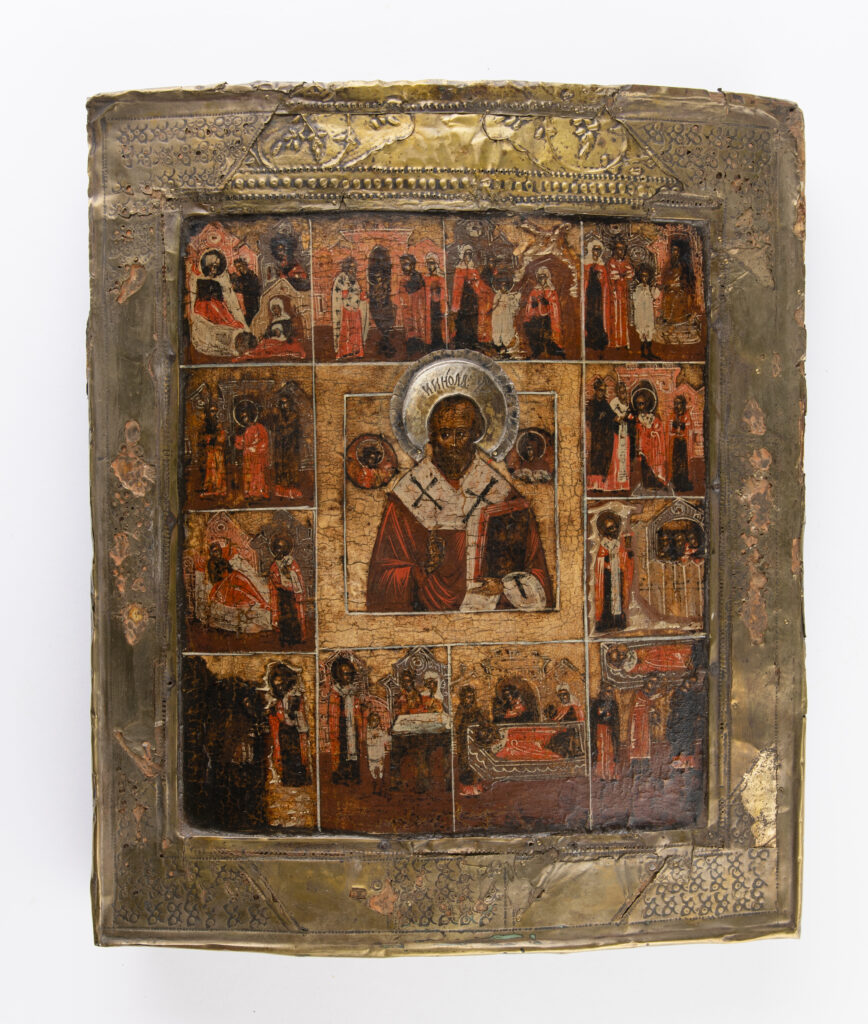

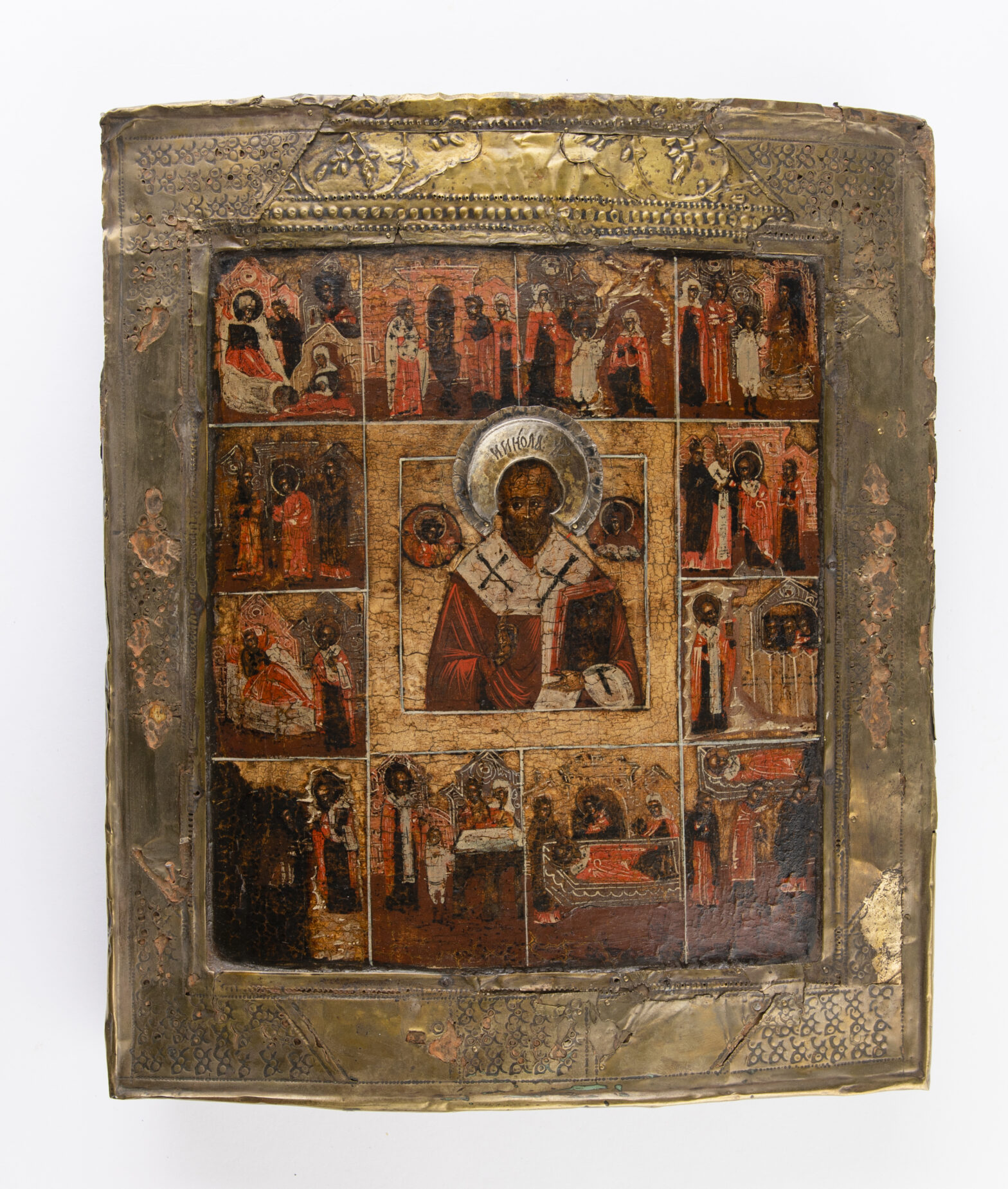

St. Nicolaus

Ett av kyrkans mest populära helgon.

Konstnär Okänd

Datering 1700 -tal

Material / Teknik Bladguld och tempera på pannå

Inventarienummer MM8733

Förvärv Gåva 1924

St. Nicolaus är en av de mest kända helgonen inom kristendomen, och han betraktas ofta som upphovet till dagens jultomte. Han levde i dagens Turkiet och det finns flera berättelser om hans livsgärningar, bland annat att han genom att dela ut påsar med guld räddade tre flickor från prostitution. Det är berättelser om händelser som dessa som sedan gjort honom till en symbol för givmildhet.

St. Nicolaus firas den 6 december men under 1800-talet i norra och västra Europa firandet alltmer till det julfirande vi känner idag, runt Jesu födelse. Visste du förresten att ordet jultomte förekommer i Sverige först 1864?

Konstnär Okänd

Datering 1400-tal

Material / Teknik Tempera på pannå

Inventarienummer MMK5053

Förvärv Inköp 1979

Bilden på Maria och Jesusbarnet är en av konsten vanligaste motiv, otaliga versioner och verk har gjorts under århundraden. Motivet blev tidigt ett så kallat huvudmotiv inom ikonmåleriet i rysk-ortodoxa kyrkan. I vissa fall har ikoner föreställande Maria och Jesusbarnet varit föremål för vallfärder, och motivet har även ansetts ha en skyddande verkan mot anfall i till exempel kloster och städer.

Ikonen skiljer sig från resten av de ryska ikonerna på väggen stilmässigt men dess motiv och utformning är sprungen ur samma religiösa bildhistoria. Det här verket har en guldgrund med punsade glorior. Punsning är en metod för att skapa mönster i metall. Ramen är i silver. Marias klädnad och mantel är gröna medan Jesus klädnad är grön med en violett mantel. Färgen grön har inom kristendomen representerat vårens vinst över vintern och då livets triumf över döden.

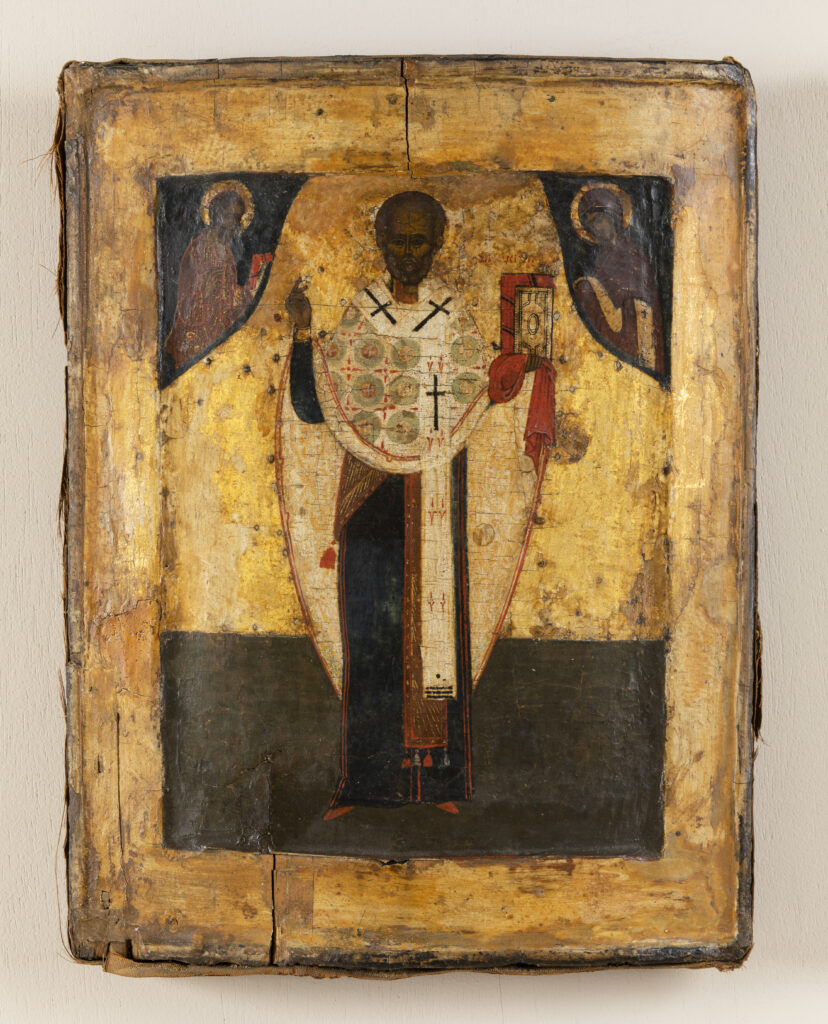

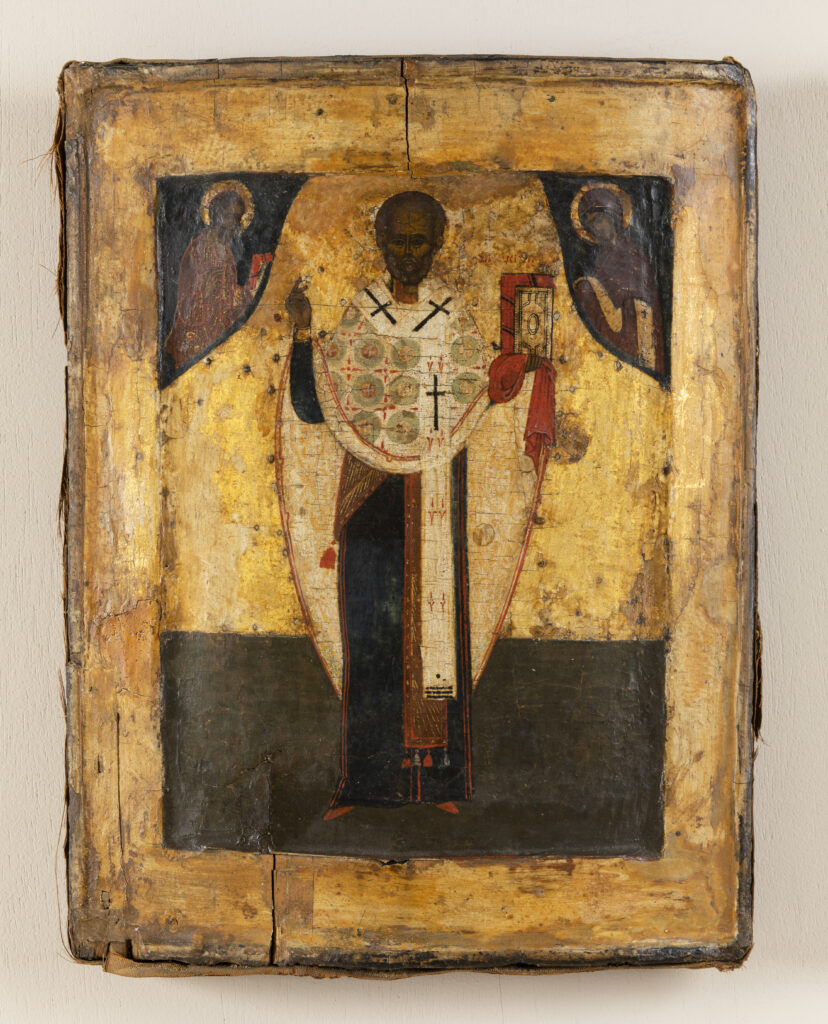

Den helige Nicolaus

Konstnär Okänd

Datering 1600-tal

Material / Teknik Olja på pannå

Inventarienummer MMK 8228

Förvärv Gåva 2000

St. Nicolaus räknas som sjöfararnas, barnens och handelsmännen skyddshelgon. Här avbildad med Jesus och Maria i var sitt hörn som överlämnar Bibeln och biskopsbandet.

Nicolaus skulle enligt legenden varit tveksam till att bli biskop. Då uppenbarade sig Jesus och Maria i en dröm och gav honom gåvorna Bibeln och biskopsbandet. Nicolaus tolkade det som ett tecken på Guds vilja och blev biskop i staden Myra (dagens Turkiet) och var verksam under 300-talet.

St. Antonius

Konstnär Okänd

Datering 1800-tal

Material / Teknik Bladguld och tempera på pannå

Inventarienummer MM8735

Förvärv Gåva 1924

Den helige Antonius är en av de mest kända ökenfäderna, som levde på 300-talet (se även St. Onuphrius). Antonius tillhörde den koptiska befolkningen i Egypten och levde många år som eremit. Trots det hade han lärjungar som han förde vidare sina tankar om det asketiska livet till. Antonius blev ovanligt gammal för sin tid, enligt berättelserna ska han ha blivit 105 år.

I konsten förekommer han ofta i motiv där djävulen försöker fresta honom.

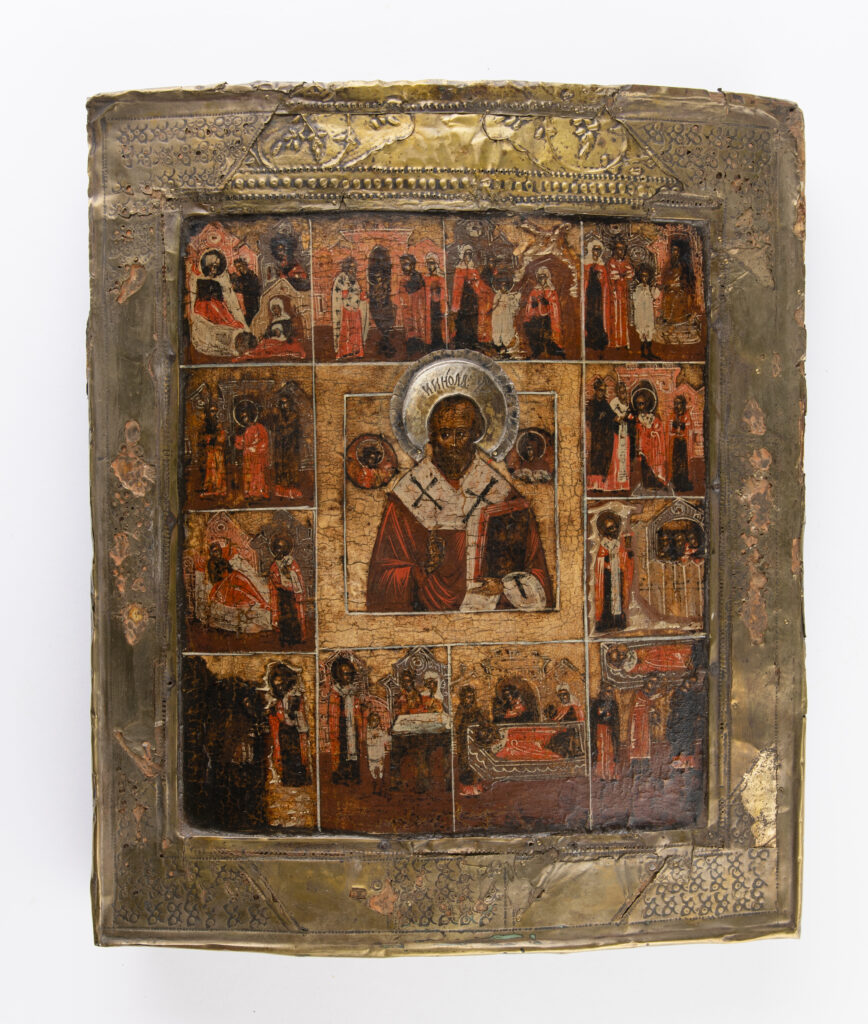

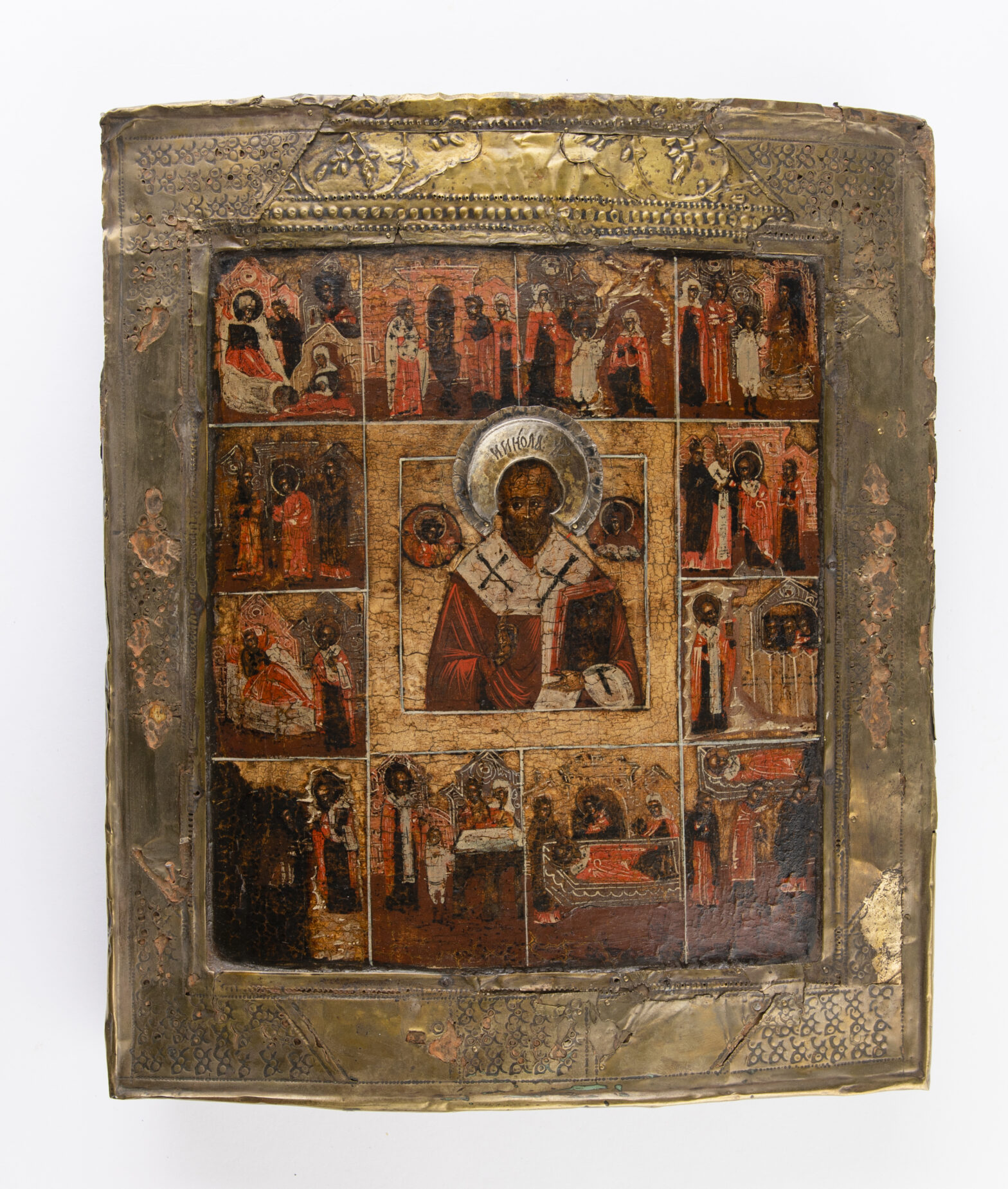

Den helige Nicolaus

Konstnär Okänd

Datering 1500 – 1600-tal

Material /Teknik Trä och mässing, äggtempera på kredering

Inventarienummer MMK 5827

Förvärv Inköp 1988

I den här ikonen illustreras scener ur helgonets liv. I centrum återges Nicolaus med Jesus och Maria. Den här typen av livsskildring kallas för vita, som betyder liv på grekiska & latin. Där kan helgonets liv följas i mindre bilder runt om ett större porträtt. Flera stycken av de ikoner som ingår i Malmö konstmuseums samling är just ikoner av typen vita.

Vill du veta mer om St. Nicholaus? Titta då närmare på två av de andra två ikonerna i utställningen, nummer 7 & 9.

Gudsmodern och ”den oförbrännbara törnbusken”

Konstnär Okänd

Datering 1500 – 1600-tal

Material / Teknik Äggtempera på kredering, på pannå

Inventarienummer MMK5829

Förvärv Inköp 1988

Kristendomens Maria kallas för flera olika namn, bland annat Jungfru Maria, Madonna men hon kan också bära titeln Guds moder. Därav kommer titeln till det här verket. I den här ikonen ser vi henne tillsammans med Jesusbarnet omringad av änglar och helgon.

Maria har genom århundraden haft en särställning inom kristendomen och varit symbol för en så kallade Maria-kult. Maria hyllades och dyrkades speciellt i Europa under tidig medeltid, men i och med reformationen fick hon en mindre roll inom kristendomen även om hon fortfarande var ett populärt motiv.

Vad menas med ”oförbrännbara törnbusken”?

I ikonens titel återfinns uttrycket ”den oförbrännbara törnbusken”. Detta kan kopplas till ikonens övre vänstra hörn, där vi kan se den brinnande törnbusken som talade till Moses.

Om Antikmontern

I montern till vänster om dig kan du se våra äldsta konstföremål i Samlingen. Det är skålar, vaser, och figurer tillverkade av lergods där det äldsta föremålet är från 1100 f.v.t. och det yngsta från 1300-talet.

Föremålen kommer från området runt Medelhavet och Mellanöstern (Grekland, Cypern, Persien) och räknas till det vi idag brukar kalla Antiken. Genom arkeologiska utgrävningar och handel har de hamnat i vår samling. Titta gärna närmare och se om det finns mönster eller detaljer som även dyker upp längre fram i utställningen och konsthistorien.

Hylla 1. Persien

Översta hyllplanet

Persisk keramik är ett relativt outforskat ämne. Arkeologiska utgrävningar har inte gjorts i samma utsträckning som i andra delar av världen, och bland den keramik som har hittats har väldigt lite blivit daterat, vilket har gjort det svårt att kartlägga den keramiska historien och utvecklingen i området. Likaså är mycket av det som grävs upp endast skärvor.

Däremot har forskare identifierat staden Kashan, i nuvarande centrala Iran, som en viktig stad för produktion av keramik. Staden har till exempel gett namn till en särskild typ av persisk keramik, som karaktäriseras av målningar av överglasyr på redan glaserat och bränt lergods. På undersidan av flera av vaserna på denna hylla står “Kashan” skrivet, vilket antyder att det är där lergodset har sitt ursprung.

Hylla 2. Cypern

Nästöversta hyllplanet

Mellan 1927–1931 ägde den svenska Cypernexpeditionen rum, vars mål var att göra extensiva arkeologiska utgrävningar på ön och dokumentera dess kulturella historia. Expeditionen leddes av arkeologen Einar Gjerstad från Uppsala universitet, som senare även var verksam vid Lunds universitet där han undervisade i klassisk fornkunskap och antikens historia. En stor andel av alla cypriotiska föremål i Malmö Konstmuseums samling grävdes förmodligen ut i samband med Cypernexpeditionen.

Opium, som utvinns ur en särskild typ av vallmo, var en vanlig drog i den antika världen – främst runt Medelhavet men även i länder som Indien och Persien. Det finns evidens för att opiumet var en viktig del av cypriotisk kultur, vilket speglas i dess antika keramik. Typiskt för cypriotisk keramik är de stora, runda kärlen, så kallade bilbil, vars form tros vara inspirerad av huvudet på en vallmoblomma. Linjerna som går runt vaserna är även karaktäriserande för cypriotisk keramik, och forskare påstår att de är gjorda för att efterlikna hur vallmoblommor skars vid utvinning av opium. Forskare har vid studier av dessa typer av kärl funnit spår av opium, som visat på att kärlen kan ha använts till att förvara opium, eller att opium har använts vid produktionen, exempelvis i färgen.

Hylla 3. Persien

Denna typ av så kallad magisk skål användes främst i Babylonien mellan 500—700-talen. Skålarna placerades upp och ned i syfte att fånga demoner och onda andar. Bland annat placerades de i nyligen bortkomna personers hem, på gravgårdar och liknande, men även i vanliga hem för beskydd.

På insidan av skålen står en förbannelse på det mandaeiska språket, och texten översatts till engelska år 1939 av den amerikanska forskaren Cyrus H. Gordon. Enligt hans översättning uppmanar förbannelsen demoner, olika typer av andar och andra onda skapelser, att bege sig från ett hem som tillhörde en man vid namn Ziztaq. Förbannelsen hotar även demonerna med att änglarna Hibil och Ptahil, viktiga figurer inom mandaeismen, regerar över dem.

Hylla 4. Persien

En stor del av Malmö Konstmuseums persiska samling donerades av eller köptes ifrån den turkiska Parisbaserade konstsamlaren Hassan Chabestari under 1930- och 40-talen. Chabestari hade en väldigt stor, privat samling av antika lergods och textilier, främst från Iran och Turkiet.

Ernst Fischer som var museichef under 1930-talet hade en nära vänskap med Chabestari, och försökte under en längre tid övertala honom till att donera eller sälja sin samling, men fick många avslag innan han till slut gick med på att donera en del av den. 1947 gick Chabestari bort i en olycka, och två år senare auktionerades resten av hans samling ut i Paris, eftersom han inte hade skrivit något testamente.

Hylla 5. Persien

En väldigt stor del av museets persiska samling består av skärvor och fragment av skålar och andra typer av kärl. Det som nu visas i utställningen representerar en bråkdel av de skärvor som museet har i sin ägo. Detta är representativt för vad som kan hittas vid utgrävningar – hela skålar och kärl är bara en minoritet av allt det som grävs upp. Även om skärvorna inte återge hela historien, ger dem oss en bild av olika motiv och mönster som varit framträdande. Exempelvis har många av dessa skärvor motiv som efterliknar blommor och blad. Skärvorna antyder även att symmetri var viktigt.

Hylla 6. Cypern

Denna typ av tjurfiguriner har hittats i många rika gravar från senare bronsålder i Cypern, och forskare undersöker huruvida de kan ha ingått i någon typ av ritual vid begravningar. Vissa av dessa tjurfiguriner har en öppning på baksidan vilket antyder att de har använts till att dricka ur, och därmed är en typ av kärl kallad rhyton (ῥυτόν), som karaktäriseras av att efterlikna djur eller djurhuvuden. På grund av den mängd tjurformade figurer och föremål med tjurmotiv som hittats i Cypern föreslår forskare att det kan ha funnits någon form av religiös, kultisk koppling.

Hylla 7. Cypern & Grekland

Tanagra (Τάναγρα)

De små statyetterna är så kallade Tanagrafigurer, vilka är formgjutna och målade terrakottafigurer. De har sitt ursprung i staden Tanagra, norr om Aten som även namngivit dem, men figurerna producerades under antiken runtom i hela Grekland och städer runt Medelhavet. Dessa figurer tros ha haft ett främst dekorativt syfte, men det finns även vissa gjorda i religiöst syfte. Det var även vanligt att begrava människor med dem som gravgåvor. Många figurer skildrar alldagliga unga män och kvinnor iklädda tidstypiska plagg, som chiton och himation vilka var vanliga typer av tunikor och sjalar som draperades över kroppen. Den större figuren har dessutom sitt hår i en så kallad “melonfrisyr”, som var väldigt populärt i det antika Grekland från 300-talet f.Kr., och förknippades med ungdomlighet. Under 1870-talet plundrades många gravar i Tanagra då folk från staden och andra närliggande orter ville åt Tanagrafigurerna. Som resultat förstördes en stor mängd gravar. Några år senare beslagtog myndigheterna olagligt utförda grävtillstånd i området.

Hylla 8. Grekland

Halsamfora (ἀμφορεύς)

Amforor karaktäriseras av dess runda form med smalare botten och dess två handtag på vardera sida. De som visas i utställningen är halsamforor, som skiljer sig från andra amforor med att de är mer ovala och mer definierad hals. Särskilda amforor har en mer spetsig botten och var gjorda för att fraktas, men dessa har fötter för att kunna stå på egen hand. Många halsamforor är dekorerade med svart figurmålning, vilket var en framträdande stil i Grekland mellan 600- och 400-talen f.Kr., som fortsatte produceras ända fram till 100-talet f.Kr. De allra flesta kärlen med svart figurmålning har sitt ursprung från Attikaregionen runt Aten. Amforornas främsta användning var att förvara olika typer av vätskor och sädesslag.

Aryballos (ἀρύβαλλος)

Aryballos är små, runda flaskor med en smal hals som användes till att förvara oljor och parfymer. De användes av många atleter, och det finns flera avbildningar av atleter med aryballoi, som hängde i remmar från deras handleder eller från väggar. Aryballoi gjordes i många olika former, utgrävare har funnit flaskor i form av huvuden, ugglor, igelkottar, fötter och snäckor.

Lekythos (λήκυθος)

Lekythosflaskor karaktäriseras av dess raka form och smala hals med ett litet handtag. Handtaget syns ofta inte när lekythoi ställs ut eller fotograferas, eftersom de är bemålade och dekorerade på motsatt sida. Lekythoi användes dels för att förvara parfymerade oljor, dels främst vid bröllop. Innan kvinnor gifte sig, smörjde de in sig med väldoftande oljor med hjälp av dessa flaskor. På grund av denna koppling var det även vanligt att ogifta kvinnor begravdes med lekythoi och smörjdes in med samma typer av oljor för att förbereda dem för giftermål i efterlivet. Det finns därmed många lekythoi med målningar som representerar förlust, saknad eller begravningsscener.

About the Icons

The word icon comes from the Greek word for image eikōʹn. Icons don’t have to be painted pictures on wood; they can also be created with textiles, mosaic, ivory, metal, and stone.

These images are regarded as not just illustrations of the Bible and other texts but as part of the Word of God. Making an icon is considered a sacred act.

But the history of icons is not so simple. During the so-called Byzantine Iconoclasm (730–843), there was a debate within the Orthodox Church about whether to even allow images. In 843, the Iconophiles (who loved imagery) won and icons became an unquestioned and necessary feature of life in the Orthodox Church.

The Resurrection of Jesus

Artist: Unknown

Date: 18th century

Medium: Tempera and gold foil on wood

Inventory number: MM8734

Acquisition: Gift 1924

This image represents Jesus as a man with a halo standing on a stone coffin, a grave. Three men are gathered below him. In the background, we see a mountain and a city.

What is an icon? Icons are sacred images used in the Orthodox Church. Icons are common in both the Greek and the Russian Orthodox Churches. Icons play an important role in the decoration of the church in the iconostasis (a wall of religious imagery), but can also be prominent in the home.

This icon represents the resurrection of Christ, which is central to Easter, the most important holiday in the Orthodox tradition. Easter Vigil, the worship service held the night before Easter Sunday, is usually considered the highpoint of the year in the Church.

Saint Onuphirus

Artist: Unknown

Date: 17th century

Medium: Tempera and gold foil on wood

Inventory number: MM8732

Acquisition: Gift 1924

A man with a long beard, holding a staff and a scroll in his hands, stands before a landscape with three high mountains, trees, and hills.

St. Onuphrius is considered one of the Desert Fathers, the first generation of Christian ascetics who lived as hermits and whose way of living was an inspiration for the development of monastic life. Onuphrius is believed to have lived and worked during the fourth century.

Holy Bishop

Artist: Unknown

Date: 18th century

Medium: Tempera and gold foil on wood

Inventory number: MM8736

Acquisition: Gift 1924

The scene shows a man dressed in red and white and wearing a cross. He is seated and holds in one hand a red book while making the sign of blessing with the other.

Why are so many icons made by unknown artists?

All of the icons on view here on the wall were created by artists who are unknown to us today, but why is that? Icons have traditionally been painted in monasteries, where the act of painting is a sacred devotion shaped by rules and procedures. The making of icons has been regarded as a sacred act or mission.

Most important is the choice of motif, and the same scenes are reproduced again and again. Thus, there has been no reason to sign each one. Especially until the sixteenth century, icons were unsigned works by artists whose names are mostly unknown. This continued even longer in Russia.

Holy Elijah

Artist: Unknown

Date: 17th century

Medium: Tempera on wood

Inventory number: MMK5081

Acquisition: Gift 1980

This icon comprises eighteen smaller images that frame a larger picture in the middle. This shows a man dressed in a fur-lined mantle and looking up at a little bird we see on his left. The smaller images represent people and events from the life of the saint. This is the largest icon on the wall (113 x 89 cm).

In Russian folklore, St. Elias was regarded as ruler over the forces of nature, especially thunder and rain, which were extremely important to farmers.

The icon is made of three rough wood panels joined together. Elias is centrally placed, surrounded by eighteen smaller frames. The icon is to be read from top to bottom, starting in the upper left corner, each picture showing a different scene from his life and works. In the right corner, for example, we see Elias dropping his mantle to the ground during his journey to heaven.

The icon was painted by the Novgorod School, which was one of the most significant schools of icon painting. They developed a very expressive style, an important part of which was the color red, as we see here. The color red could be used in place of traditional gilding both for economic reasons and to stand out as an eye-catcher.

Archangel Gabriel

Artist: Unknown

Date: 16 /17th century

Medium: Tempera and brass on wood

Inventory number: MMK5828

Acquisition: Purchase 1988

In this picture we see a head with its face looking off to the left. The angel depicted here has curly hair and a halo.

The Archangel Gabriel features in all of the Abrahamic religions (Christianity, Judaism, and Islam). In Christianity, Gabriel is considered one of the foremost archangels and appears several times in the Bible as the messenger of God.

Gabriel is usually depicted in the annunciation scene from the Book of Luke, in which he is sent by God to tell Mary that she is going to give birth to a son.

Saint Paraskevi

Artist: Unknown

Date: 18th century

Medium: Tempera on wood

Inventory number: MMK8229

Acquisition: Gift 2000

The image depicts a woman clothed in a mantle with a halo around her head.

Paraskeva is also known as Paraskevi, which means Friday in Greek. Therefore, in icon painting she is often called Saint Friday. Paraskeva is often portrayed as a personification of Christ’s suffering on Good Friday, and thus cannot be considered a historical person. Nevertheless, stories have emerged of the special role she plays in the business world and that her presence was important to commerce at public markets.

In the icon on view in our exhibition, Paraskeva carries a martyr’s cross in her right hand and a lexicon in her left.

Saint Nicolaus

Artist: Unknown

Date: 18th century

Medium: Tempera and gold foil on wood

Inventory number: MM8733

Acquisition: Gift 1924

St. Nicholas is one of the best-known saints of Christendom, and he is often regarded as the inspiration for today’s Santa Claus. He lived in what is now Turkey, and there are many stories about his life of great deeds, including the time he saved three girls from prostitution by handing out bags of gold. It is stories about events like this one that later turned him into a symbol of benevolence.

St. Nicholas is celebrated on December 6th, but in northern and western Europe during the nineteenth century that celebration increasingly evolved into the Christmas holiday we know today focused on the birth of Jesus.

Madonna and Child

Artist: Unknown

Date: 15th century

Medium: Tempera on wood

Inventory number: MMK5053

Acquisition: Purchase 1979

The image of Mary and the baby Jesus is one of the most common motifs in art, with countless versions of the scene captured in works over the centuries. From early on, the scene became a major motif of icon painting in the Russian Orthodox Church. In some cases, icons representing Mary and the baby Jesus have been destinations for pilgrimages, and the scene has even been thought to hold protective power against attack in monasteries and cities.

This icon differs stylistically from the other Russian icons on the wall, but its motif and composition spring from the same religious image history. This piece has a gold background with stamped halos. Stamping, or embossing, is a method of creating relief patterns in metal. The frame is silver. Maria’s gown and mantle are green, while Jesus is clothed in green with a violet mantle. In Christianity, the color green represents the victory of spring over winter and thus the triumph of life over death.

Saint Nicholaus

Artist: Unknown

Date: 17th century

Medium: Tempera on wood

Inventory number: MMK8228

Acquisition: Gift 2000

St. Nicholas is considered the patron saint of sailors, children, and merchants. Here he is depicted together with Jesus and Mary, each in their own corners, presenting him with the Bible and the bishop’s sash.

According to the legend, Nicholas was supposed to have been reluctant to become a bishop. Then Jesus and Mary appeared to him in a dream and gave him the gifts of the Bible and the sash. Nicholas interpreted it as a sign of God’s will, and he became a bishop in the city of Myra (in what is now Turkey), where he worked during the fourth century.

Anthony the Great

Artist: Unknown

Date: 19th century

Medium: Tempera and gold foil on wood

Inventory number: MM8735

Acquisition: Gift 1924

St. Anthony was one of the best-known Desert Fathers, who lived in the fourth century (see also St. Onuphrius). Anthony belonged to the Coptic community of Egypt and lived for many years as a hermit. Nevertheless, he had acolytes who shared his ideas about the life of asceticism with the world. It is said that he lived to be 105, a remarkably old age for that time.

In art, he is often depicted in scenes in which the devil tries to tempt him.

Saint Nicolaus

Artist: Unknown

Date: 16/17th century

Medium: Tempera on wood, brass

Inventory number: MMK5827

Acquisition: Purchase 1988

This icon illustrates scenes from the life of a saint. In the center we see Nicholas together with Jesus and Mary. This kind of image of a life is called a vita icon, from the Latin word for life. Here we can follow the life of the saint in smaller pictures surrounding a larger portrait. Several of the icons that are included in Malmö Konstmuseum’s collection are this kind of vita icon.

Do you want to know more about St. Nicholas? Have a closer look at two of the other icons in the exhibition: numbers 7 and 9.

The Mother of God and the Burning Bush

Artist: Unknown

Date: 16/17th century

Medium: Tempera on wood

Inventory number: MMK5829

Acquisition: Purchase 1988

Christianity’s Mary is known by many names, including the Virgin Mary and the Madonna, but she is also called the Mother of God. Thus the title of this work. In this icon we see her together with the baby Jesus and surrounded by angels and saints.

Over the centuries, Mary has held a special place in Christianity and been the focus for the so-called Cult of the Virgin Mary. Mary was especially revered and worshiped in Europe during the Middle Ages, but with the Protestant Reformation she took on a lesser role in the Church, though she continued to be popular motif in art.

What do we mean by the “burning bush”?

The title of this icon makes reference to the “burning bush.” In the upper left corner, we see the burning bush that spoke to Moses in the Old Testament story.

About the Antiquity

In the display case to your left, you can see the oldest art objects in our collection. They are bowls, vases, and figures made of earthenware, the oldest dating back to about 1100 BC and the youngest from the fourteenth century AD.

The objects come from the region around the Mediterranean Sea and the Middle East (Greece, Cyprus, Babylonia, Persia) and belong to the period now usually known as Antiquity. Through archaeological excavations and trade, they eventually ended up in our collection. Take a closer look and see if you can identify any patterns or details that recur later on in our exhibition and in the history of art.

Shelf 1. Persia

Top shelf

Persian ceramics are a relatively unexplored topic. Archaeological excavations have not been undertaken here to the same extent as in the rest of the world, and very little of the recovered ceramic art has been dated, which has made it difficult to map out the history and development of ceramics in the region. What’s more, much of what has been dug up was in fragments.

On the other hand, researchers have identified the city of Kashan, in what is now central Iran, as an important center for the production of ceramic arts. For example, Kashan is the name of a particular type of Persian ceramics characterized by painting already glazed and fired earthenware with a second glazing. On the underside of several of the vases on this shelf it says “Kashan,” which suggests that these earthenware objects originated in that city.

Shelf 2. Cyprus

The Swedish Cyprus Expedition took place between 1927 and 1931, its goal to do extensive archaeological excavations and to document the island’s cultural history. The expedition was led by the archaeologist Einar Gjerstad of Uppsala University. He later worked at Lund University, where he taught Classical archaeology and ancient history. A large proportion of the Cypriot objects in Malmö Konstmuseum’s collection were likely excavated in conjunction with the Cyprus Expedition.

Opium, which is extracted from a particular kind of poppy, was a common drug in the ancient world, especially around the Mediterranean Sea, but in other countries as well, such as India and Persia. There is some evidence that opium played an important role in Cypriot culture, and this is reflected in its antique ceramics. Typical of Cypriot ceramics are the large, round vessels known as bilbil, whose form is believed to be inspired by the head of a poppy flower.

The lines that ring these vases are also characteristic of Cypriot ceramics, and researchers posit that they were made to mimic how poppies are cut in the extraction of opium. In studies of this type of vessel, researchers have found traces of opium, which indicates that they were used to store the drug, or that opium was used in making them, perhaps to give them color.

Shelf 3. Persia

This type of so-called magical vessel was used primarily in Babylonia from the sixth through the eighth century. The bowls were placed upside down for the purpose of capturing demons and evil spirits. They were placed in cemeteries and in the home when someone died, for example, but could also be used in the home for protection.

On the inside of the vessel, a curse is written in the Mandaic language, and the words were translated into English in 1939 by the American researcher Cyrus H. Gordon. According to one such translation, these curses challenge demons, various kinds of spirits, and other evil creatures to get out of a home belonging to a man named Ziztaq. The curse also threatens those demons with the wrath of the angels Hibil and Ptahil, important figures in Mandaism.

Shelf 4. Persia

Much of Malmö Konstmuseum’s Persian collection was donated by or purchased from the Paris-based Turkish art collector Hassan Chabestari during the 1930s and 40s. He had an enormous private collection of antique earthenware and textiles, primarily from Iran and Turkey.

Ernst Fischer, who was the museum’s director during the 1930s, had a close friendship with Chabestari and tried for a long time to convince him to donate or sell his collection, but Fischer was rebuffed many times before Chabestari eventually agreed to donate a portion of it. In 1947, Chabestari died in an accident, and two years later the rest of his collection was auctioned off in Paris because he had never signed a will.

Shelf 5. Persia

A very large portion of the museum’s Persian collection comprises splinters and fragments of bowls and other kinds of vessels. The objects now on view in this exhibition represent only a fraction of the pieces owned by the museum. They are representative of what can be found in excavations—whole bowls and vessels are only a small part of everything that has been unearthed.

Although these fragments don’t convey the full history, they give us a glimpse of some of the more prominent motifs and patterns. For example, many of these fragments have motifs that look like flowers and leaves. They also indicate that symmetry was important.

Shelf 6. Cyprus

This type of bull figurine has been found in many well-to-do graves from the late Bronze Age on Cyprus, and researchers are studying whether it might have been part of some kind of burial ritual. Some of these bull figures have an opening on the back, which suggests that they have been used to drink out of and are thus a type of vessel called a rhyton (ῥυτόν), which is characterized by looking like an animal or an animal head.

Because of the great many bull-formed figures and objects with bull motifs that have been found on Cyprus, researchers believe there may have been some form of religious, cult connection.

Shelf 7. Cyprus & Greece

Tanagra (Τάναγρα)

These small statuettes are so-called Tanagra figures, which were form-cast and painted terracotta sculptures. They get their name from the city of Tanagra, north of Athens, where they originated, but such figures were produced all over Ancient Greece as well as in cities around the Mediterranean.

Tanagra figures are believed to have had a primarily decorative purpose, although some were made for religious practices. It was also common for people to be buried with them as grave goods. Many of these figures depict average young men and women clothed in the typical garments of the day, such as the chiton and himation, a common form of tunic and shawl draped over the body.

The larger figure also has hair done in a “melon coiffure,” which was extremely popular in Ancient Greece starting in the fourth century BC and was associated with youthfulness. In the 1870s, many graves in Tanagra were plundered as people from the city and the surrounding region sought to recover Tanagra figures. As a result, a great many graves were destroyed. Several years later, the authorities confiscated illegally executed excavation permits throughout the area.

Shelf 8. Grecee

Neck amphora (ἀμφορεύς)

Amphoras are characterized by round forms that narrow at the bottom with handles on either side. Those on view in our exhibition are neck amphoras, which have more ovular silhouettes and more clearly articulated necks. Certain amphoras have more pointed bottoms and were made for shipping, while others have feet that allow them to stand on their own.

Many neck amphoras were decorated with painted black figures, a style that was prominent in Greece between the seventh and fifth centuries BC and continued to be produced until the second century BC. The vast majority of vessels with black figure painting originate from the Attica region surrounding Athens. Amphoras were used primarily for storing various types of liquids and grains.

Aryballos (ἀρύβαλλος)

An aryballos is a small, round jar with a narrow neck that was used to store oils and perfumes. They were often used by athletes, and there are many depictions of athletes with an aryballos hanging from a strap around their wrist or from a wall. Aryballoi were made in many forms, and archaeologists have found jars in the shape of heads, owls, hedgehogs, feet, and snails.

Lekythos (λήκυθος)

Lekythos jars are characterized by an erect form and narrow neck with a small handle. Often the handles are hidden when lekythoi are exhibited or photographed, since they are painted and decorated on the opposite side. Lekythoi were used to store perfumed oil, particularly for weddings. In preparation for getting married, women were anointed with aromatic oils from such jars. Because of this connection to weddings, it was common for unmarried women who died to be buried with lekythoi and to be anointed with the same kinds of oils in preparation for marriage in the afterlife. There are therefore many lekythoi with paintings that represent loss, absence, or funeral scenes.