Fisk som fiskar

Evolutionen gör att arter utvecklar bättre och bättre jaktmetoder, för att få tag i mat. Ett sätt, som används av vissa fiskarter, är att locka bytesdjur med sin egen kropp! Om en del av fiskens kropp ser ut som en god mask eller räka, kommer andra djur att försöka äta upp den. Då kan fisken överraska, och sluka det hungriga bytesdjuret som blivit lurad av betet. Precis som när människor metar och sätter en mask på kroken – men istället för ett metspö är det en del av fiskens egen kropp!

Det finns många olika arter av djuphavsmarulkar, men av naturliga skäl är det få människor som sett dem på riktigt.

Bild: Masaki-Miya-et-al.-CC-BY

En djuphavsmarulk med sitt "fiskespö" i pannan.

Bild: NOAA-Photo-Library-CC-BY

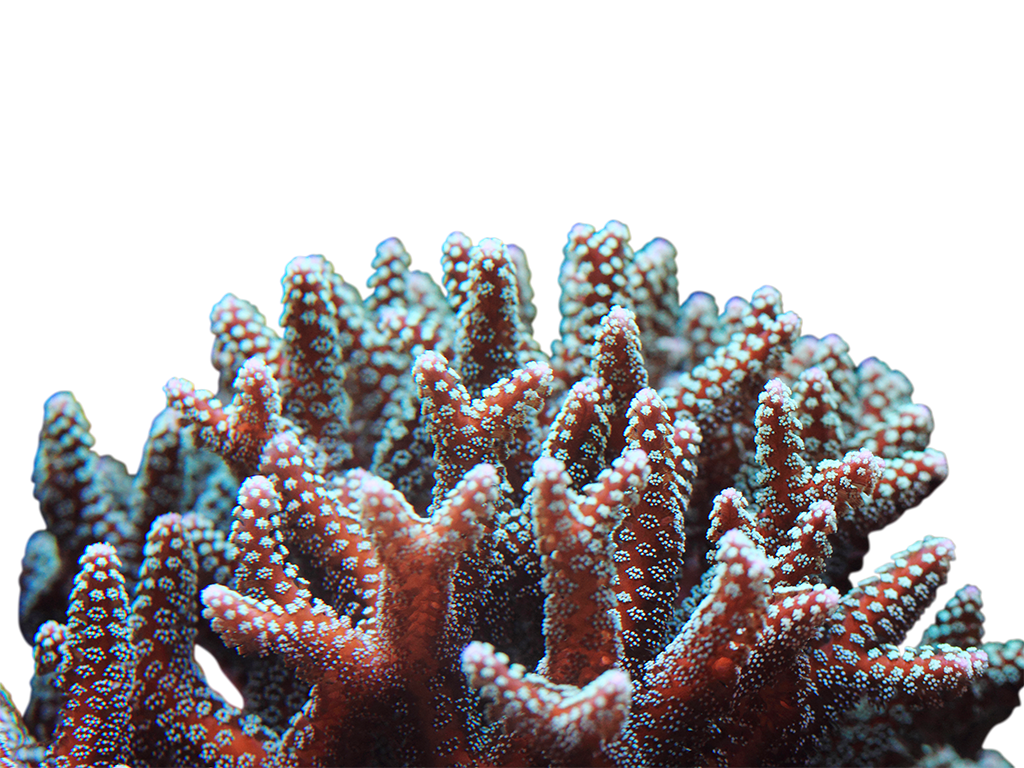

Tångulkar är släkt med djuphavsmarulkar, men lever på grundare vatten i korallrev. De har också lockbeten i pannan.

Bild: Betty-Wills-CC-BY-SA

Tångulkars bete har många olika utseenden, anpassade efter olika bytesdjur.

Bild: Rickard-Zerpe-CC-BY-SA

En tångulk som lockar till sig bytesdjur med sitt bete.

Djuphavsmarulk med lysande metspö

Den mest kända gruppen fiskar som lurar till sig byten med sin egen kropp är djuphavsmarulkar. De har omvandlat en del av en fena, till ett spröt på huvudet. Längst ut på sprötet sitter en liten lysande del, som rör sig som en mask. Det är djurhavsmarulken själv som skapar ljuset, och viftar på sprötet. Andra fiskar tror att det är mat och hugger på betet. Då suger marulken snabbt in bytet och äter upp det. Djuphavsmarulken finns i alla världshaven och den lever på mycket stort djup på över 300 m, där det är helt mörkt.

Wobbegongen är en bottenlevande haj. Den använder sin stjärtfena för att imitera en liten fisk - för att locka till sig större fiskar att äta.

Bild: fiftygrit-CC-BY-NC

Alligatorsköldpaddan jagar genom att ligga helt stilla och gapa. I munnen har den en tunga som den vickar på - och som då ser precis ut som en liten mask. Det får fåglar och andra djur att hugga på tungan - och sköldpaddan stänger blixtsnabbt sin vassa mun och får sig ett mål mat.

Bild: gilbert_neil-CC-BY-NC

Spindelhuggormens svans liknar och rör sig precis som en spindel, för att locka till sig fåglar som ormen kan äta.

Bild: Omid-Mozaffari-Public-Domain

Den amerikanska vattensnoken ligger och lurar i vattnet och låter tungan vicka över vattenytan. Det liknar en liten insekt, och fiskar som vill äta insekten lockas direkt till ormens mun.

Bild: Roy-Bridgeman-Public-Domain

Dödsormen är en mycket giftig orm från Australien. Den använder sin svanstipp - som liknar en mask - som lockbete för att fånga bytesdjur.

Bild: Jean-and-Fred-CC-BY

Också växter kan lura till sig bytesdjur med lockbeten. Venus flugfälla är en köttätande växt, vars specialanpassade blad liknar och luktar som blommor för att locka till sig nektarhungriga insekter.

Bild: Fae-CC-BY

Ålar och ormar med stjärt som en mask

När vissa djur har sitt lockbete i pannan, har andra det i svansen. Pelikanålens lockbete sitter längst ut på stjärten. Änden liknar en piska, och är också självlysande, precis som betet i djuphavsmarulkens panna. Ålen har ett enormt gap, som gör att den kan svälja byten som är större än den själv är. Den lever på ända ner till 3000 meter djupt vatten, där det är totalt mörker.

Vissa ormar har samma sätt att locka till sig byten. Dödsormen, en giftsnok som lever i Australien, har också ett lockbete på svansen. Den viftar med svanstippen i närheten av sitt huvud, för att efterlikna en mask. När ett hungrigt djur kommer nära hugger ormen direkt.

Tångulk

Antennarius sp.

Metspö i pannan och fenor som tassar

Tångulkar är en familj av fiskar, bestående av ca 45 olika arter, släkt med marulkar. I familjen finns släktet Antennarius, som innehåller 11 arter. Vissa av arterna kan vara mycket svåra att skilja på. Alla tångulkar har fenor som ombildats till något som liknar ben och tassar! Med dem kan de gå långsamma promenader över bottnen. Men den kanske mest spektakulära egenskapen hos tångulkarna är – att den främsta fenstrålen i ryggfenan är ombildad till ett slags metspö! Strålen är lång och utstickande, och i änden sitter ett bete – en del av fenan som liknar en mask, en liten fisk eller något annat som tångulkens bytesdjur gärna vill äta.

Bild: Betty-Wills-CC-BY-SA

Viftar med betet

Tångulkar har flera olika jakttekniker, men den vanligaste är att ligga helt still, och vifta med det lilla metspöet. Betet längst ut gör andra djur intresserade, och när de kommer tillräckligt nära öppnar tångulken sitt enorma gap. Sugkraften in i fiskens mun är så stor, att allt löst som befinner sig i närheten dras rätt in i munnen och sväljs. Men det är inte alltid tångulken behöver använda sitt bete för att få mat. Tångulkar har otroliga kamouflage, och smälter in perfekt i omgivningen. Det gör att räkor och småfisk kan komma nära helt utan att det finns ett lockbete utfällt. Ibland händer det också att tångulken aktivt smyger sig på sitt byte – med sina ombildade, benliknande fenor.

Bild: Betty-Wills-CC-BY-SA

Pressar ut vatten genom rör

Tångulkar lever naturligt i tropiska korallrev, där de är perfekt anpassade för att smälta in. En tångulk som kommer till en ny miljö kan på ett par veckor ändra färg så att den passar in på den nya platsen. Kroppen kan se ut som koraller, stenar, alger eller svampdjur. Den kan vara fläckig, hårig eller knölig. I stället för gällock, som de flesta fiskar har vid bröstfenorna, har tångulken små rör som leder till gälarna. Rören används inte bara för andning, utan också för förflyttning! Tångulken kan suga in vatten genom munnen, och pressa den ut genom gälrören. På så sätt skapas en jetström som flyttar fisken framåt.

Olika arter av tångulk kan ha väldigt olika färg och utseende.

Bild: Steve-Childs-CC-BY

Tångulkens bröstfenor är ombildade så att de liknar tassar.

Bild: Darijus-Strasunskas-CC-BY-NC

Litet yngel av tångulk.

Bild: Izuzuki-CC-BY-SA

Rosa variant av tångulk.

Bild: Nick-Hobgood-CC-BY-SA

En ljus variant av tångulk.

Bild: Izuzuki-CC-BY-SA

Tångulkar kan vara väldigt välkamouflerade.

Bild: Steve-Childs-CC-BY

En välkamouflerad tångulk.

Bild: Bernard-DUPONT-CC-BY-SA

Utbredningsområde i världen

I tropiska och subtropiska hav världen över.

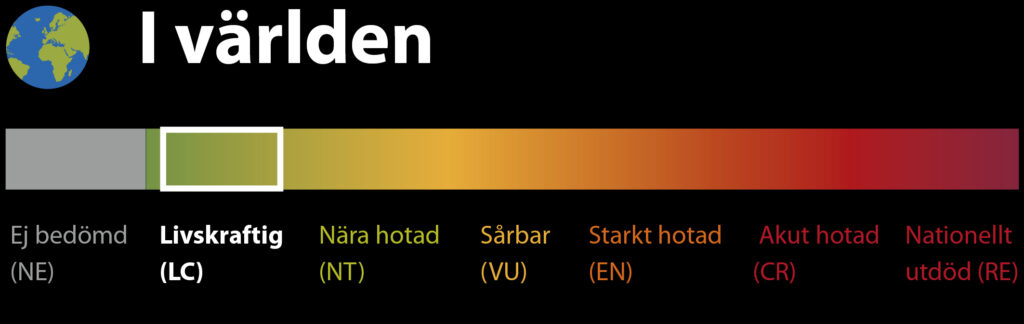

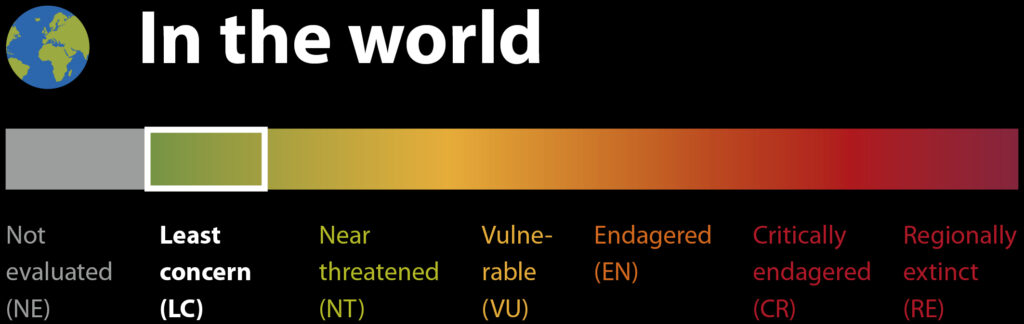

Hotstatus enligt Rödlistan

Reglerad inom handel

CITES: Ej listad.

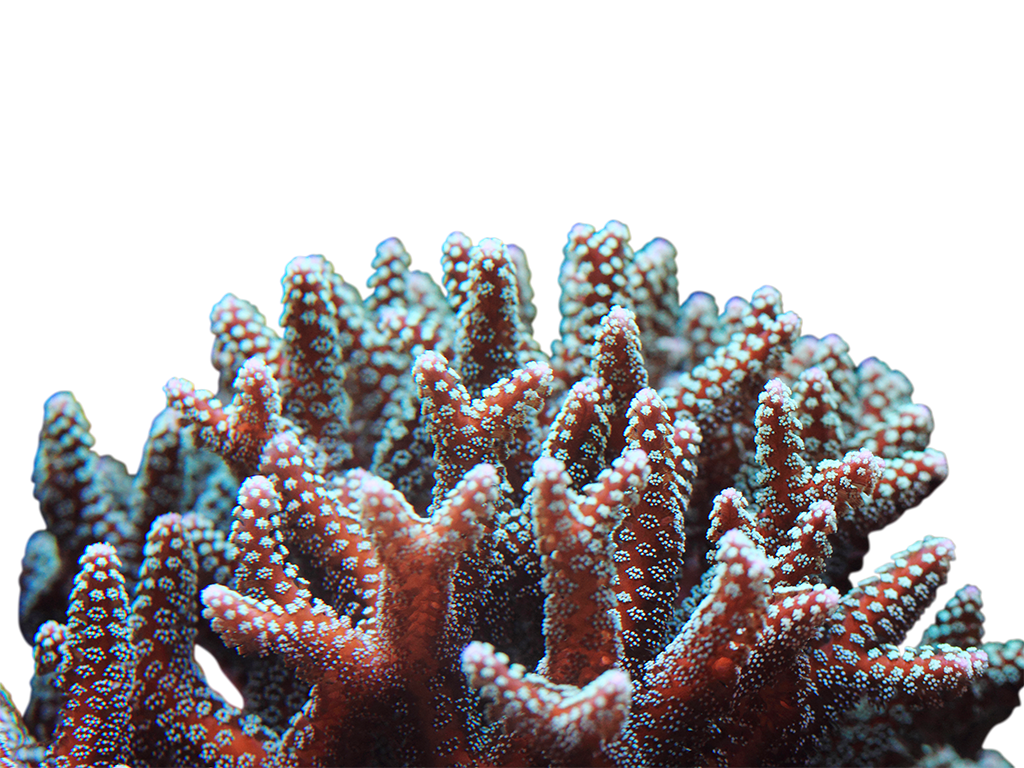

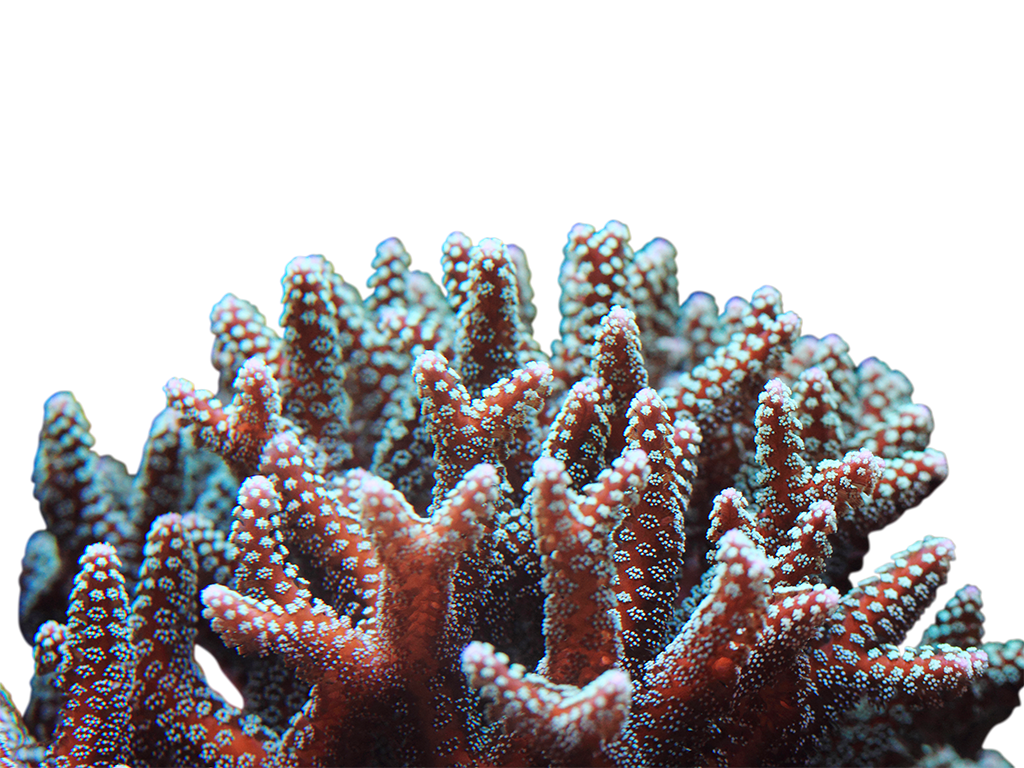

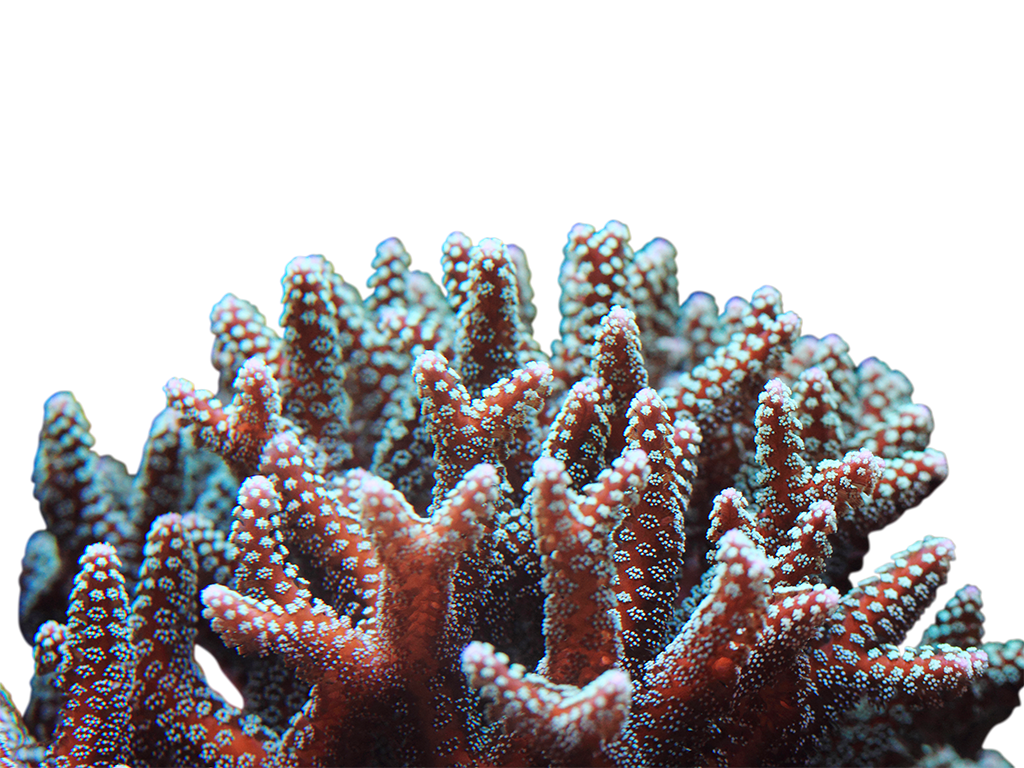

Stenkoraller

Bygger grunden till korallrev

Stenkoraller har hårda skelett, som de bygger av kalcium de plockar upp från havsvattnet. Korallerna är beroende av hög kalkhalt i vattnet för att få hållbara skelett. Koraller lever i haven över stora delar av jorden. De är vanligast i tropiska vatten, men lever också i svenska vatten utanför Bohuslän.

Stenkoraller har stor betydelse för att bygga upp korallreven, eftersom de bildar hårda kalkskelett som blir kvar även efter korallens död. Stenkoraller kan ha många olika former, som greniga, runda, skivformade eller knöliga. Stenkoraller som lever i kolonier kan till exempel likna en hjärna, eller ett älghorn.

Stenkorallernas hårda skelett är det som utgör grunden för världens korallrev.

Bild: Toby-Hudson-CC-BY-SA

Korallreven innehåller många gömställen för alla möjliga arter.

Bild: Nick-Hobgood-CC-BY-SA

Acroporakoraller kan likna hjortdjurens horn.

Bild: MDC-Seamarc-Maldives-CC-BY-SA

Stenkorall med en yta som påminner om en hjärna.

Bild: Ryan-McMinds-CC-BY

Korallers strukturer kan vara väldigt olika.

Bild: Ryan-McMinds-CC-BY

Stenkoraller kan växa som tickor eller stora sjok med lavar.

Bild: Williams-et-al.-CC-BY

Under de mjuka, långa tentaklerna gömmer sig anemonkorallens hårda kalkskelett.

Bild: Bernard-DUPONT-CC-BY-SA

Svampkoraller i Indonesien.

Bild: Bernard-DUPONT-CC-BY-SA

En kallvattenskorall med spännande växtsätt, som lever på djup ner till 1500 meter.

Ett bulligt, svampigt växtsätt för en stenkorall.

Bild: Diego-Delso-CC-BY-SA

Har alger som inneboende

Stenkoraller tillhör ordningen koralldjur, och det finns ca 2500 arter. En korall är oftast en hel koloni av små polyper, som var och en är en egen individ – ofta kopior av varandra. Polyper har en säckliknande kropp som skyddas av ett yttre kalkskelett. Stenkoraller lever oftast, men inte alltid, i stora kolonier.

Många arter av stenkoraller lever i symbios med så kallade zooxantheller, som är en typ av encelliga alger. Zooxantheller lever inuti polyperna. De bidrar till korallens energiförsörjning, och behöver solljus som når ner genom vattnet för att överleva. Stenkoraller i kolonier är hårdare och tåligare än ensamlevande. Men de stenkoraller som lever ensamma, kan finnas ända ner till 6000 meters djup! Djuplevande koraller får sin näring genom att äta plankton som flyter förbi i vattnet.

Varje polyp är en egen individ, som tillsammans bildar en korallkoloni.

Bild: Peter-Young-Cho-CC-BY-SA

I mitten av polypen sitter koralldjurets mun.

Bild: Justin-Casp-CC-BY-SA

Små polyper som delvis är utfällda.

Bild: David-Witherall-and-Pete-Morrison-CC-BY

Mikroskopiskt små polyper med fångstarmar.

Bild: Narrissa-Spies-CC-BY-SA

En polyp som alldeles nyss fäst mot ett underlag. De bruna prickarna är korallens inneboende alger, zooxantheller.

Bild: Narrissa-Spies-CC-BY-SA

Zooxantheller kallas de alger som är de vanligaste inneboenden i koraller. Här i mikroskop.

Bild: Tim-Wijgerde-CC-BY-SA

Vad är Rödlistan?

Rödlistning är ett sätt att bedöma om olika djur- och växtarter är utrotningshotade utifrån kriterier som hur många djur eller växter som finns av arten och hur utbredda de är. En nationell rödlistning bedömer artens risk att dö ut inom ett lands gränser. Den internationella rödlistningen bedömer artens risk att dö ut över hela jorden.

Läs mer

Om rödlistning i Sverige: Artdatabanken, www.artdatabanken.se

Om rödlistning i världen: International Union for Conservation of Nature, IUCN, www.iucn.org

Vad är CITES?

För att bekämpa olaglig handel med djur och växter finns en internationell överenskommelse om handel, som heter CITES. CITES innebär att utrotningshotade djur och växter inte får köpas eller säljas mellan olika länder utan tillstånd.

CITES klassar olika arter i olika kategorier (som kallas Appendix I, II och III) beroende på hur hotad arten är. Ju större hotet från handeln är desto högre skydd. Inom EU finns ytterligare skydd för arter i CITES. EU:s egen klassning har fyra steg: A-D.

Bild: Steve-Hillebrand

Förbjudet att handla med viltfångade arter

Högst skydd mot handel har de arter som är inom kategori A och B. Här gäller oftast att handel mellan EU och övriga världen är förbjuden utan tillstånd. Arter som är CITES A eller B-klassade får inte heller köpas eller säljas inom EU om det inte kan bevisas att de har lagligt ursprung och inte fångats i det vilda.

Att använda växter eller djur för att tillverka souvenirer och annat är också förbjudet. Den som bryter mot reglerna kan dömas till böter eller fängelse.

Kontrollera spridning av arter

Arter som är CITES C-klassade är utrotningshotade i ett visst land men inte nödvändigtvis i hela världen. CITES D-klassning betyder att en art importeras i så stort antal att de behöver regleras för att inte riskera att sprida sig okontrollerat där de inte hör hemma.

Fish with a fishing rod

Evolution causes species to develop better and better hunting methods to get food. One way, used by some fish species, is to attract prey with their own body! If part of the fish’s body looks like a tasty worm or shrimp, other animals will try to eat it. The fish may make a surprise attack, and will devour the hungry prey that has been tricked by the bait. Just like when people fish and put a worm on the hook – but instead of a fishing rod, it’s part of the fish’s own body!

There are many different species of deep-sea anglerfish, but naturally, only a few people have seen them in real life.

Photo: Masaki-Miya-et-al.-CC-BY

A deep-sea anglerfish with its "fishing rod" attatched to its forehead.

Photo: NOAA-Photo-Library-CC-BY

Frogfish are related to deep-sea anglerfish, but lives in coral reefs in more shallow waters. They also carry their lure on their foreheads.

Photo: Betty-Wills-CC-BY-SA

Frogfishes' lures have many shapes and looks, adapted to different kinds of prey.

Photo: Rickard-Zerpe-CC-BY-SA

A frogfish with its lure out.

Deep-sea anglerfish with glowing fishing rod

The most famous group of fish that lure prey with their own body is the deep-sea anglerfishes. They have converted part of a fin into a pole-like rod on the head. At the end of the rod is a small glowing part that moves like a worm. The deep-sea anglerfish itself creates the light, and waves the rod. Other fish think it’s food and take the bait. That’s when the anglerfish quickly sucks in the prey and eats it. The deep-sea anglerfish is found in all the oceans of the world and lives at very great depths, always greater than 300 metres, where it is completely dark.

The wobbegong is a bottom-dwelling shark. It uses its tail fin to mimic a small fish - luring larger fish for the wobbegong to eat.

Photo: fiftygrit-CC-BY-NC

The alligator snapping turtle hunts by lying completely still with its mouth open. In the mouth it has a tongue that looks like a small worm when wiggled. It makes birds and other animals go for the tongue - and the turtle quickly snapps its mouth shut, and gets a meal.

Photo: gilbert_neil-CC-BY-NC

The spider-tailed horned vipers tail looks and moves just like a spider, to lure birds for the snake to eat.

Photo: Omid-Mozaffari-Public-Domain

The American aquatic garter snake lures in the water, and wiggles its tongue above the surface. It looks like a small bug, and hungry fish are lured directly into the snake's mouth.

Bild: Roy-Bridgeman-Public-Domain

The common death adder is a very venomous snake from Australia. It uses the tip of its tail - mimicking a worm - as a lure to catch prey.

Photo: Jean-and-Fred-CC-BY

Plants can also use lures to catch prey. Venus flytrap is a carnivorous plant, with leaves looking and smelling like flowers - to attract insects hungry for nectar.

Photo: Fae-CC-BY

Eels and snakes with worm-like tails

While some animals wear their lure on their forehead, others wear it on their tail. The pelican eel’s lure is at the end of its tail. The end resembles a whip, and is also luminescent, just like the lure on the forehead of the deep-sea anglerfish. The eel has a huge mouth, which allows it to swallow prey larger than itself. It lives in waters as deep as 3,000 metres, where there is total darkness.

Some snakes have the same way of attracting prey. The common death adder, a venomous snake that inhabits Australia, also has a lure on its tail. It bends its tail over its head and wags the tip to imitate a worm. When a hungry animal comes close, the snake immediately strikes.

Frogfish

Antennarius sp.

Fishing rod on the forehead and fins as paws

Frogfish is a family of fish, consisting of about 45 different species, related to anglerfish. The family includes the genus Antennarius, which includes 11 species. Some of the species can be very difficult to distinguish. All frogfish have fins that have been transformed into something that resembles legs and paws! With them, they can go for slow walks across the bottom. But perhaps the most spectacular feature of the frogfish is that the first dorsal spine is transformed into a kind of fishing rod! The spine is long and protruding, and at the end is a bait – a part of the fin that resembles a worm, a small fish or something else that the frogfish’s prey likes to eat.

Photo: Betty-Wills-CC-BY-SA

Waving the bait

Frogfish have several different hunting techniques, but the most common is to lie completely still, and wave the small fishing rod. The bait at the tip makes other animals interested, and when they get close enough, the frogfish opens its huge mouth. The suction force into the fish’s mouth is so great that everything loose that is nearby is drawn right into the mouth and swallowed. But the frogfish does not always need to use its bait to get food. Frogfish have incredible camouflage, and blend in perfectly with their surroundings. This means that shrimp and small fish can get really close without the bait unfolded. Sometimes the frogfish also actively sneaks up on its prey – with its transformed fins resembling legs.

Photo: Betty-Wills-CC-BY-SA

Squeezes water out through tubes

Frogfish live naturally in tropical coral reefs, where they are perfectly adapted to blend in. A frogfish that arrives in a new environment can change colour in a couple of weeks to adapt to the new location. The body can look like corals, rocks, algae, or sponges. It can be mottled, hairy, or lumpy. Instead of gill covers, which most fish have at their pectoral fins, the frogfish has small tubes leading to the gills. The tubes are used not only for breathing, but also for locomotion! The frogfish can suck in water through its mouth, and squeeze it out through the gill tubes. In this way, a jet stream is created that moves the fish forward.

Different species of frogfish have very different colours and appearances.

Photo: Steve-Childs-CC-BY

The pectoral fins of the frogfish are evolved into "paws".

Photo: Darijus-Strasunskas-CC-BY-NC

A frogfish fry.

Photo: Izuzuki-CC-BY-SA

A pink frogfish.

Photo: Nick-Hobgood-CC-BY-SA

A frogfish with pale colouration.

Photo: Izuzuki-CC-BY-SA

Frogfish can be very well camouflaged.

Photo: Steve-Childs-CC-BY

A well-camouflaged frogfish.

Photo: Bernard-DUPONT-CC-BY-SA

Distribution worldwide

In tropical and subtropical seas around the world.

Threat based on the Red List

Trade regulations

CITES: Ej listad.

Stony corals

The foundation for coral reefs

Stony corals have hard skeletons, which they build from the calcium they absorb from seawater. Corals depend on high levels of calcium in the water in order to develop sturdy skeletons. Corals live in the oceans across large parts of the world. They are most common in tropical waters, but also inhabit the Swedish waters off Bohuslän.

Stony corals play an important role in the building of coral reefs, as they form hard calcareous skeletons that remain even after the coral has died. Stony corals come in many different shapes, such as branching, rounded, disc-shaped or lumpy. For example, stony corals living in colonies may resemble a brain or moose antlers.

The hard skeleton of the stony corals are what makes the foundation of the world's coral reefs.

Photo: Toby-Hudson-CC-BY-SA

The coral reefs have lots of hiding places for many different species.

Photo: Nick-Hobgood-CC-BY-SA

Acropora corals can resemble antlers of deers.

Photo: MDC-Seamarc-Maldives-CC-BY-SA

A stony coral with a surface that resembles a brain.

Photo: Ryan-McMinds-CC-BY

There are many different structures of stony corals.

Photo: Ryan-McMinds-CC-BY

Stony corals can grow like bracket fungi, or large patches of lichen.

Photo: Williams-et-al.-CC-BY

The hard calcium skeleton of the anemone coral hides under its long, soft tentacles.

Photo: Bernard-DUPONT-CC-BY-SA

Fungia corals in Indonesia.

Photo: Bernard-DUPONT-CC-BY-SA

A species of cold water coral with an astonishing way of growing. It lives on depths down to 1,500 meters.

A stony coral growing in a round, lumpy way.

Photo: Diego-Delso-CC-BY-SA

Algae are common inhabitants

Stony corals belong to the class Anthozoa, and there are about 2,500 species. A coral is usually a whole colony of small polyps, each of which is a separate individual – often copies of each other. Polyps have a sack-like body protected by an outer calcareous skeleton. Stony corals usually, but not always, live in large colonies.

Many species of stony corals live in symbiosis with so-called zooxanthellae, a type of single-celled algae. Zooxanthellae live inside the polyps. They contribute to the energy supply of the coral and depend on sunlight penetrating deep into the water to survive. Stony corals in colonies are harder and more resilient than those living alone. But the stony corals that live alone can be found as deep as 6,000 metres! Deep-dwelling corals get their food from eating plankton that float by in the water.

Each polyp is an individual animal, together creating a coral colony.

Photo: Peter-Young-Cho-CC-BY-SA

The coral polyp's mouth is located in the middle of the animal.

Photo: Justin-Casp-CC-BY-SA

Small, partly extracted polyps.

Photo: David-Witherall-and-Pete-Morrison-CC-BY

Tiny polyps with even smaller tentacles.

Photo: Narrissa-Spies-CC-BY-SA

A recently attached polyp. The brown dots are the inhabitant algae of the coral - zooxanthellae.

Photo: Narrissa-Spies-CC-BY-SA

The most common algae living inside corals are zooxanthellae. The photo shows zooxanthellae seen through a microscope.

Photo: Tim-Wijgerde-CC-BY-SA

What is the Red List?

The Red List is a way to assess whether different animal and plant species are at risk of extinction based on criteria such as how many animals or plants of a species exist and how widely distributed they are. A national Red List assesses a species’ risk of dying out within national borders. The international Red List assesses a species’ risk of dying out worldwide.

Read more

About the Red List in Sweden: The Swedish Species Information Centre (Artdatabanken), www.artdatabanken.se/en/

About the Red List worldwide: The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), www.iucn.org

What is CITES?

CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) is a treaty that makes it illegal to buy or sell animals and plants that are at risk of extinction between countries without a permit.

CITES classifies species into different categories (called Appendix I, II and III) depending on how endangered each species is. In addition, the more the species is threatened by international trade, the higher its level of protection. Within the EU, CITES-listed species are further classified and protected by the EU’s own classification system. This has four Annexes, from A to D.

Photo: Steve-Hillebrand

Ban on trading wild-caught species

The highest protection against trade is given to CITES-listed species included in the EU’s Annexes A and B. Usually this means that trade between the EU and the rest of the world is illegal without a permit. There is also a ban on trading these species within the EU unless it can be proved that they have a lawful origin and were not caught in the wild.

It is also forbidden to use plants or animals to make souvenirs etc. Anyone who breaks these regulations can be fined or imprisoned.

Controlling the spread of species

CITES-listed species that are in the EU’s Annex C are classified as endangered in at least one country but not necessarily in the whole world. An Annex D classification means that individual members of a species may be imported to the extent that they do not need to be regulated to avoid any risk of them spreading uncontrollably where they do not belong.