Signalera med färg

I naturen använder sig växter och djur av färger på många olika vis. När det är dags att para sig får många starkare färger. Detta för att synas bättre och imponera på både partners och rivaler. Fasantupparna runt Malmö Museer blir extra färgstarka på våren, för att sedan bli färglösa och smälta bättre in i omgivningen igen efter parningstiden.

Bild: Lukasz-Lukasik-CC-BY-SA

Kamouflage, varning, temperatur eller humör

Olika färger kan också användas som både kamouflage och som varningssignal. En del färger hjälper till att hålla rätt temperatur och att skydda sig mot parasiter. För många djur sker dessa förändringar av sig själv vid vissa tider på året, som till exempel när hararna får sin vita vinterpäls. Vitt skyddar bättre mot rovdjurens hungriga ögon när det finns snö.

Andra arter kan aktivt ändra på färg och utseende efter behov. Fiskar, reptiler, kräldjur och bläckfiskar har celler som innehåller flera sorters färgpigment. Sådana celler kallas kromatoforer. Genom att få kromatoforerna att svälla eller dra ihop sig kan djuret ändra färg och utseende.

Många djur byter färg med årstiderna för att kamouflera sig bättre, som den här bergsharen i vinterpäls.

Bild: Bouke-ten-Cate-CC-BY-SA

Pilgiftsgrodors starka färger används som varning - jag är giftig att äta!

Bild: H.-Krisp-CC-BY

Att visa upp sin färgstarka haklapp är ett sätt för anolisödlan att både varna andra hanar och att locka till sig honor.

Bild: Gailhampshire-CC-BY

På mindre än en sekund kan sepiabläckfisken Sepia latimanus ändra både färg och struktur på sin hud.

Bild: Nick-Hobgood-CC-BY-SA

Alla bläckfiskar är mästare på att kamouflera sig, men kan också ändra färg beroende på humör, till exempel att varna för att den är irriterad.

Bild: Johanna-Rylander-Malmö-Museer

Bläckfiskar som ändrar färg och lyser i mörkret

Bläckfiskar är mycket bra på detta och kan ändra sitt utseende snabbt. Förutom att anpassa sig till olika underlag och gömma sig kan de med hjälp av kromatoforer också skrämmas och överraska fiender eller byten. Vissa bläckfiskar kan på kemisk väg sända ut ljus för att locka till sig byten, locka till parning eller för att kommunicera med andra bläckfiskar. Detta kallas för biolumincens.

Oftast använder kameleonter inte sina färger för att kamouflera sig, utan för att kommunicera, eller reglera temperatur. Men den gröna grundfärgen hos många kameleonter hjälper också för att smälta in.

Bild: Mr.-Shambulingu-CC-BY-SA

Prickarna på den trehornade kameleontens kropp blir tydligare när den är arg eller irriterad.

Bild: Benjamin-Klingebiel-CC-BY-SA

Panterkameleonthonor blir mycket mörka efter parning, för att visa att de inte längre är intresserade av att para sig.

Bild: Roland-zh-CC-BY-SA

Kameleonter visa känslor med färg

Kameleonter är ödlor som är kända för sina färgförändringar. Det sägs ofta att kameleonter byter färg för att kamouflera sig. Djuren kan i för sig normalt vara kamouflagefärgade, ofta gröna, men färgbytena beror inte främst på en anpassning till bakgrunden. I stället är det kameleontens känsloläge som oftast styr färgbytena. Om de känner sig hotade av andra kameleonter byter de färg för att skrämma bort den andra kameleonten.

Färgbyten signalerar också att kameleonten är villig – eller ovillig – att para sig. Dessutom reglerar kameleonterna sin temperatur genom att mörkna så att de absorberar mer solljus och blir varmare. Är de för varma ljusnar de istället, för att minska solljusets påverkan.

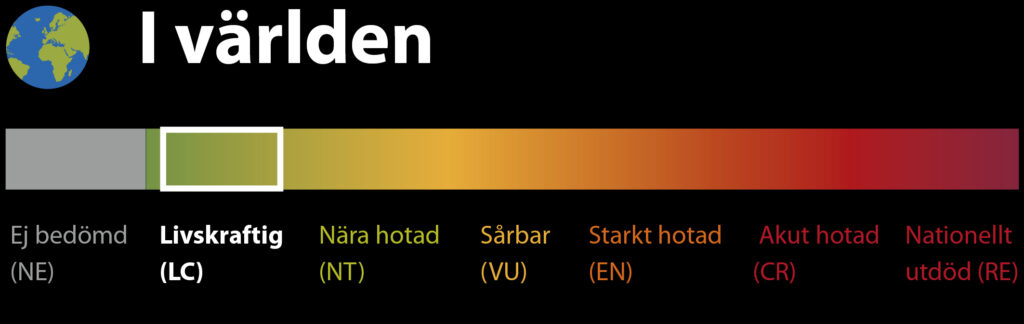

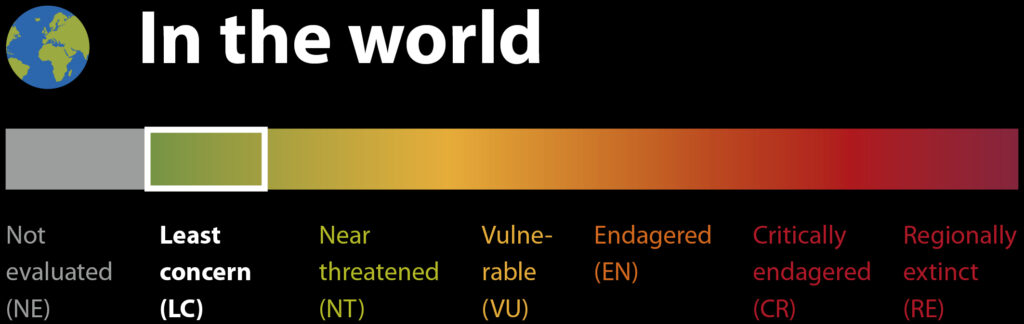

Vad är Rödlistan?

Rödlistning är ett sätt att bedöma om olika djur- och växtarter är utrotningshotade utifrån kriterier som hur många djur eller växter som finns av arten och hur utbredda de är. En nationell rödlistning bedömer artens risk att dö ut inom ett lands gränser. Den internationella rödlistningen bedömer artens risk att dö ut över hela jorden.

Läs mer

Om rödlistning i Sverige: Artdatabanken, www.artdatabanken.se

Om rödlistning i världen: International Union for Conservation of Nature, IUCN, www.iucn.org

Panterkameleont

Furcifer pardalis

Lång klibbig tunga

Kameleonter har väldigt bra syn och de rör sig mycket sakta och försiktigt när de jagar efter mat. De fångar sitt byte genom att skjuta ut sin långa och klibbiga tunga.

Panterkameleonter lever ensamma och hanarna kan vara mycket territoriella och aggressiva mot varandra.

Bild: Surrey-John-CC-BY-SA

Bild: Ellika-Nordström-Malmö-Museer

Flera olika arter

Panterkameleonten är en av de mest färgrika kameleonterna och finns i en mängd olika färger. Allt från röda, gröna till blå.

Forskare har kommit fram till att det troligtvis finns elva olika arter av panterkameleonter på Madagaskar. Inte bara en art som man tidigare har trott.

Ett hot mot panterkameleonterna är den omfattande förstörelsen av deras naturliga levnadsområden. Madagaskars unika skogar skövlas för att göra träkol eller ge plats för jordbruk och bete.

Bild: Fanomezantsoa-Andria-CC-BY

Bild: Heinonlein-CC-BY-SA

Bild: Marco Schmidt-CC-BY-SA

Bild: Roland zh-CC-BY-SA

Bild: Donar Reiskoffer-CC-BY

Bild: Christophe Germain-CC-BY-SA

Utbredningsområde i världen

Nordöstra

Madagaskar.

Vit markering = Utbredningsområde

Hotstatus enligt Rödlistan

Reglerad inom handel

CITES: B-listad.

Vad är CITES?

För att bekämpa olaglig handel med djur och växter finns en internationell överenskommelse om handel, som heter CITES. CITES innebär att utrotningshotade djur och växter inte får köpas eller säljas mellan olika länder utan tillstånd.

CITES klassar olika arter i olika kategorier (som kallas Appendix I, II och III) beroende på hur hotad arten är. Ju större hotet från handeln är desto högre skydd. Inom EU finns ytterligare skydd för arter i CITES. EU:s egen klassning har fyra steg: A-D.

Bild: Steve-Hillebrand

Förbjudet att handla med viltfångade arter

Högst skydd mot handel har de arter som är inom kategori A och B. Här gäller oftast att handel mellan EU och övriga världen är förbjuden utan tillstånd. Arter som är CITES A eller B-klassade får inte heller köpas eller säljas inom EU om det inte kan bevisas att de har lagligt ursprung och inte fångats i det vilda.

Att använda växter eller djur för att tillverka souvenirer och annat är också förbjudet. Den som bryter mot reglerna kan dömas till böter eller fängelse.

Kontrollera spridning av arter

Arter som är CITES C-klassade är utrotningshotade i ett visst land men inte nödvändigtvis i hela världen. CITES D-klassning betyder att en art importeras i så stort antal att de behöver regleras för att inte riskera att sprida sig okontrollerat där de inte hör hemma.

Signalling with colour

In nature, plants and animals use colours in many different ways. When it’s time to mate, many of them take on brighter colours. This is to make them more visible as well as to impress both partners and rivals. The pheasant cocks around Malmö Museums become particularly colourful in the spring before becoming colourless again to blend in better with their surroundings after the mating season.

Photo: Lukasz-Lukasik-CC-BY-SA

Colour as camouflage, warning, temperature regulation or mood

Different colours can also be used both as camouflage and as a warning signal. Some colours help to maintain the right temperature and to protect against parasites. For many animals, these changes happen automatically at certain times of the year, such as when hares get their white winter coats. White provides better protection against the hungry eyes of predators when there is snow.

Other species can actively change colour and appearance as needed. Fish, reptiles and cephalopods have cells that contain several types of colour pigments. Such cells are called chromatophores. By causing these chromatophores to swell or contract, the animal can change its colour and appearance.

Many animals, like this hare, change colour to better camouflage themselves, along with the changes of seasons.

Photo: Bouke-ten-Cate-CC-BY-SA

Poison dart frogs have bright colours to warn others: don't eat me!

Photo: H.-Krisp-CC-BY

The anole lizard displays its colourful throat, both as a warning to other males, and to impress females.

Photo: Gailhampshire-CC-BY

In less than a second, the broadclub cuttlefish is able to change both colour and structure of its skin.

Photo: Nick-Hobgood-CC-BY-SA

All octopuses are masters of camouflage, but they are also able to change their colours depending on mood. This is a way for the octopus to warn others that it is irritated.

Photo: Johanna-Rylander-Malmö-Museer

Cephalopods that change colour or glow in the dark

Cephalopods, like octopus and cuttlefish, are very good at this and can change their appearance quickly. As well as adapting to different surfaces and hiding, they can also use chromatophores to intimidate and surprise enemies or prey. Some cephalopods can chemically emit light to attract prey, to entice mating partners or to communicate with other cephalopods. This is called bioluminescence.

Chameleons mostly use their colours to communicate or regulate their temperature - and not to camouflage themselves. But the green ground colour in many chameleons, helps to blend in.

Photo: Mr.-Shambulingu-CC-BY-SA

The spots on the three-horned chameleon's body get bigger and more apparent when the chameleon is angry or annoyed.

Photo: Benjamin-Klingebiel-CC-BY-SA

Female panther chameleons get very dark after mating, to show other males that they are no longer interested in mating.

Photo: Roland-zh-CC-BY-SA

Chameleons express emotions with colour

Chameleons are lizards known for their colour changes. It is often said that chameleons change colour to camouflage themselves. The animals themselves may normally be camouflaged, often green, but the colour changes are not primarily a matter of blending in with the background. Instead, it is the chameleon’s emotional state that usually drives the colour changes. If they feel threatened by other chameleons, they change colour to scare them away.

Colour changes also signal the chameleon’s willingness – or unwillingness – to mate. In addition, chameleons regulate their temperature by darkening so they can absorb more sunlight and get warmer. If they are too warm, they instead turn lighter, to reduce the impact of the sunlight.

What is the Red List?

The Red List is a way to assess whether different animal and plant species are at risk of extinction based on criteria such as how many animals or plants of a species exist and how widely distributed they are. A national Red List assesses a species’ risk of dying out within national borders. The international Red List assesses a species’ risk of dying out worldwide.

Read more

About the Red List in Sweden: The Swedish Species Information Centre (Artdatabanken), www.artdatabanken.se/en/

About the Red List worldwide: The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), www.iucn.org

Panther Chameleon

Furcifer pardalis

Long, sticky tongue

Chameleons have excellent eyesight and move very slowly and carefully when they hunt for food. They catch their prey by putting out their long, sticky tongue.

Panther chameleons live alone and the males can be very territorial and aggressive to each other.

Photo: Surrey-John-CC-BY-SA

Photo: Ellika-Nordström-Malmö-Museer

Several different species

The panther chameleon is one of the most colourful chameleons and comes in many different colours ranging from red and green to blue.

Researchers have concluded that there are probably 11 different species of panther chameleon on Madagascar and not just one species as previously believed.

One threat to panther chameleons is the extensive destruction of their natural habitat. Madagascar’s unique forests are being clear cut to make charcoal or to make room for crops and grazing.

Photo: Fanomezantsoa-Andria-CC-BY

Photo: Heinonlein-CC-BY-SA

Photo: Marco Schmidt-CC-BY-SA

Photo: Roland zh-CC-BY-SA

Photo: Donar Reiskoffer-CC-BY

Photo: Christophe Germain-CC-BY-SA

Distribution worldwide

Northeast

Madagascar.

White marking = Distribution

Threat based on the Red List

Trade regulations

CITES: B-listed.

What is CITES?

CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) is a treaty that makes it illegal to buy or sell animals and plants that are at risk of extinction between countries without a permit.

CITES classifies species into different categories (called Appendix I, II and III) depending on how endangered each species is. In addition, the more the species is threatened by international trade, the higher its level of protection. Within the EU, CITES-listed species are further classified and protected by the EU’s own classification system. This has four Annexes, from A to D.

Photo: Steve-Hillebrand

Ban on trading wild-caught species

The highest protection against trade is given to CITES-listed species included in the EU’s Annexes A and B. Usually this means that trade between the EU and the rest of the world is illegal without a permit. There is also a ban on trading these species within the EU unless it can be proved that they have a lawful origin and were not caught in the wild.

It is also forbidden to use plants or animals to make souvenirs etc. Anyone who breaks these regulations can be fined or imprisoned.

Controlling the spread of species

CITES-listed species that are in the EU’s Annex C are classified as endangered in at least one country but not necessarily in the whole world. An Annex D classification means that individual members of a species may be imported to the extent that they do not need to be regulated to avoid any risk of them spreading uncontrollably where they do not belong.