Invasiva arter

En invasiv art är en art som flyttats från ett ekosystem till ett annat och som snabbt breder ut sig och konkurrerar ut arter som lever naturligt på platsen. En invasiv art kan vara ett djur, en växt, en svamp eller till och med mikroorganismer och bakterier. Ibland blir de nya arterna ett hot mot hela ekosystemet och den biologiska mångfalden. Invasiva arter sprids med hjälp av oss människor, antingen medvetet eller omedvetet.

Bild: CSIRO-CC-BY

Kaniner släpptes ut för att skjutas

På 1800-talet släpptes mängder av kaniner ut i Australien. Kaninerna var tänkta att bli ett roligt jaktbyte på jordägarnas marker. Men kaninerna förökade sig snabbt och skapade stora problem. De åt upp jordbrukarnas odlingar, och utrotade många vilda växter som var unika för Australien. Idag finns det mer än 300 miljoner kaniner i Australien, och de är fortfarande ett stort problem.

Bild: smudger888-CC-BY

Inflyttad fisk

Nilabborren finns naturligt i många floder och sjöar i Afrika. Fisken kan bli två meter lång, och väga upp till 200 kilo. Nilabborren är en bra matfisk, och handeln med nilabborre är en viktig inkomstkälla för flera länders ekonomi. Men när nilabborren inplanterades i Victoriasjön på 1950-talet ledde det till en ekologisk kollaps. Nilabborren förökade sig snabbt och tog död på andra fiskarter. Många arter av ciklider som bara fanns i Victoriasjön utrotades. Biologer menar att mer än 200 fiskarter dog ut på grund av nilabborren.

Bild: Foto-Reves-CC-BY-SA

Resenärer och fripassagerare

Nuförtiden transporteras ofta mat, jordbruksprodukter och andra varor långa sträckor i hela världen. Vår handel har blivit global. Detta gör också att arter får lättare att sprida sig. Den spanska skogssnigeln har på grund av handel med grönsaker och trädgårdplantor spridit sig från sitt ursprung i Spanien och södra Frankrike över hela Europa. Den kallas för mördarsnigel, för att den är så glupsk att den till och med äter sina egna släktingar. Den förökar sig lätt och ställer till stora problem i trädgårdar och odlingar.

Bild: CarlosVdeHabsburgo-CC-BY-SA

Manet utan biljett

Den vitprickiga australiska maneten finns numera i stora delar av världen. Egentligen hör den hemma i havet som omger Australien. Men maneten har följt med handelsfartygen i deras ballasttankar. Det är tankar som fylls med vatten för balansens skull, när fartyget inte har någon last. När fartygen sen lastas på, töms tankarna ibland i främmande vatten. Då följer maneter och andra organismer med ut. Den vita australiska maneten kan också sitta fast på fartygens skrov och lifta till andra delar av världen. Maneten äter stora mängder av plankton som de inhemska arterna behöver för att överleva.

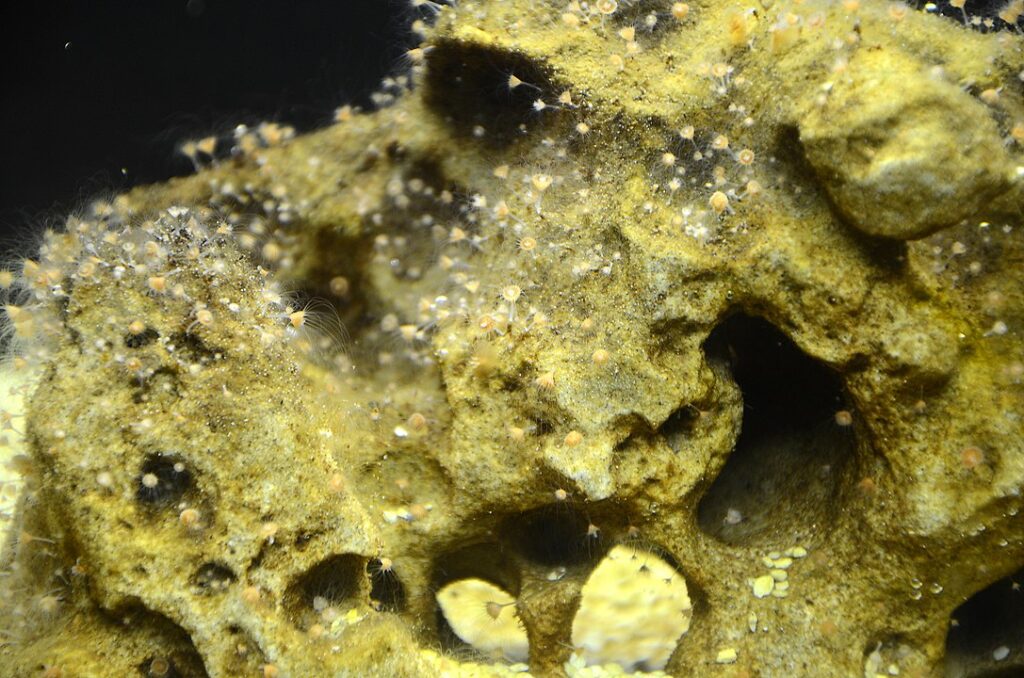

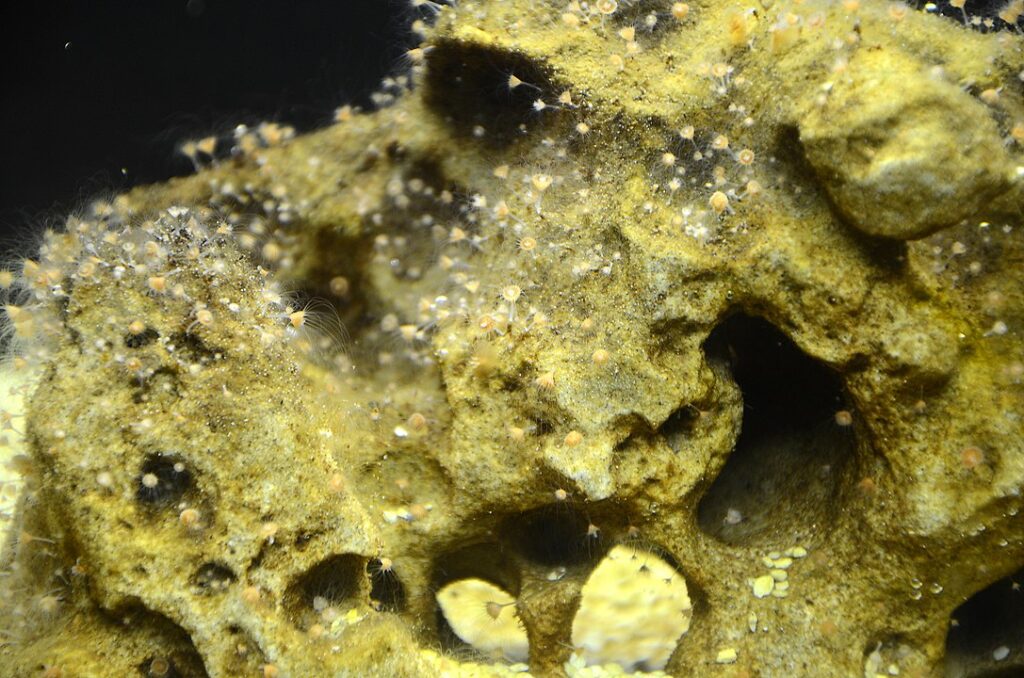

Australisk vitprickig manet

Phyllorhiza punctata

Svagt giftiga

Maneter är så kallade nässeldjur, släkt med till exempel koraller och anemoner. Alla maneter har nässelceller, och vitprickig australisk manet har långa nässelceller med ett svagt gift. Giftet är inte farligt för människor.

Vitprickig australisk manet simmar fritt i havet i stora stim, och trivs bäst i hög salthalt. Arten kan simma långa sträckor, och ett stim kan äta helt rent på stora mängder djurplankton i ett begränsat område i havet. När maneterna tillfälligt blir riktigt många, kan det leda till att andra arter periodvis blir utan mat.

Bild: Johannes-Maximilian-CC-BY-SA

Förökar sig på två olika sätt

Alla maneter har ett speciellt och ganska komplicerat sätt att föröka sig på, med flera olika stadier. När vuxna vitprickiga australiska maneter ska föröka sig, sprutar hanmaneten spermier ut genom munnen i vattnet, som honan fångar upp med sin mun. Hon filtrerar spermierna ner till sitt reproduktionsorgan, där äggen befruktas.

När larverna kläckts lämnar de honans kropp och fortsätter utvecklingen på havsbotten. De växer fast till så kallade polyper. Polyperna reproducerar sig också, men på ett annat sätt än vuxna maneter. Polyperna förökar sig genom delning, där en polyp skapar flera kopior av sig själv. De små kopiorna simmar fritt i vattnet och växer så småningom upp till stora, vuxna maneter. Detta gör att det blir många fler vuxna maneter, än de polyper som hanarna och honorna producerar tillsammans.

Bild: Amada44-CC-BY

Liftat med fartyg

Vitprickig australisk manet har blivit en invasiv art. Invasiv betyder att en art hamnat på en plats där den normalt inte hör hemma och därför gör skada. Arter som räknas som invasiva är ofta snabba på att föröka sig och har mycket få naturliga fiender. När polyper från vitprickig australisk manet har växt fast på fartygsskrov, har arten kunnat sprida sig över stora delar av världen. Maneten har gjort stor skada på det naturliga djurlivet i bland annat Mexikanska golfen och Medelhavet.

Utbredningsområde i världen

Australien och flera andra tropiska hav.

Vit markering = Utbredningsområde

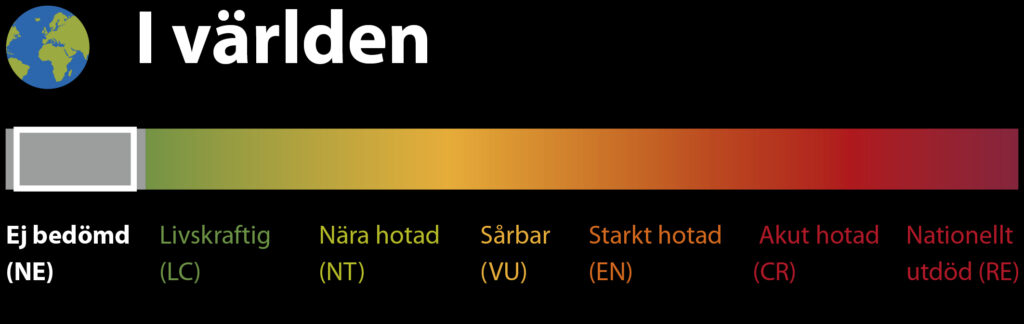

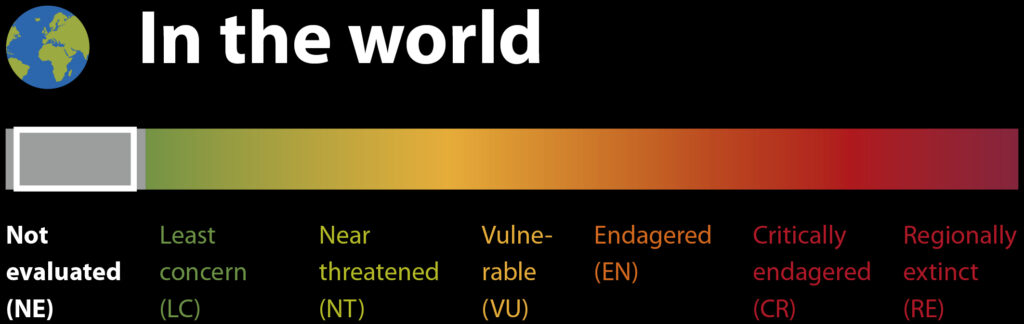

Hotstatus enligt Rödlistan

Reglerad inom handel

CITES: Ej listad.

Vad är Rödlistan?

Rödlistning är ett sätt att bedöma om olika djur- och växtarter är utrotningshotade utifrån kriterier som hur många djur eller växter som finns av arten och hur utbredda de är. En nationell rödlistning bedömer artens risk att dö ut inom ett lands gränser. Den internationella rödlistningen bedömer artens risk att dö ut över hela jorden.

Läs mer

Om rödlistning i Sverige: Artdatabanken, www.artdatabanken.se

Om rödlistning i världen: International Union for Conservation of Nature, IUCN, www.iucn.org

Vad är CITES?

För att bekämpa olaglig handel med djur och växter finns en internationell överenskommelse om handel, som heter CITES. CITES innebär att utrotningshotade djur och växter inte får köpas eller säljas mellan olika länder utan tillstånd.

CITES klassar olika arter i olika kategorier (som kallas Appendix I, II och III) beroende på hur hotad arten är. Ju större hotet från handeln är desto högre skydd. Inom EU finns ytterligare skydd för arter i CITES. EU:s egen klassning har fyra steg: A-D.

Bild: Steve-Hillebrand

Förbjudet att handla med viltfångade arter

Högst skydd mot handel har de arter som är inom kategori A och B. Här gäller oftast att handel mellan EU och övriga världen är förbjuden utan tillstånd. Arter som är CITES A eller B-klassade får inte heller köpas eller säljas inom EU om det inte kan bevisas att de har lagligt ursprung och inte fångats i det vilda.

Att använda växter eller djur för att tillverka souvenirer och annat är också förbjudet. Den som bryter mot reglerna kan dömas till böter eller fängelse.

Kontrollera spridning av arter

Arter som är CITES C-klassade är utrotningshotade i ett visst land men inte nödvändigtvis i hela världen. CITES D-klassning betyder att en art importeras i så stort antal att de behöver regleras för att inte riskera att sprida sig okontrollerat där de inte hör hemma.

Invasive species

An invasive species is a species that has moved from one ecosystem to another and is rapidly spreading, outcompeting species that live naturally in the area. An invasive species can be an animal, a plant, a fungus, or even micro-organisms and bacteria. Sometimes the new species become a threat to the entire ecosystem and biodiversity. Invasive species are spread with the help of humans, either consciously or unconsciously.

Photo: CSIRO-CC-BY

Rabbits were released to be shot

In the 1800s, large numbers of rabbits were released in Australia. The rabbits were meant to be a fun hunting prey on the landowners’ land. But the rabbits multiplied quickly and created big problems. They devoured farmers’ crops, and made many wild plants unique to Australia extinct. Today, there are more than 300 million rabbits in Australia, and they are still a major problem.

Photo: smudger888-CC-BY

Fish that have moved in

The Nile perch is found naturally in many rivers and lakes in Africa. The fish can grow to be two metres in length, and weigh up to 200 kilograms. The Nile perch is a good culinary fish, and the Nile perch trade is an important source of income for the economies of several countries. But when the Nile perch was introduced into Lake Victoria in the 1950s, it led to an ecological collapse. The Nile perch multiplied rapidly and killed off other fish species. Many species of cichlids that were only found in Lake Victoria became extinct. Biologists believe that more than 200 species of fish became extinct due to the Nile perch.

Photo: Foto-Reves-CC-BY-SA

Passengers and stowaways

Nowadays, food, agricultural products and other goods are often transported long distances throughout the world. Our trade has become global. This also makes it easier for species to spread. Due to the trade of vegetables and garden plants, the Spanish slug has spread from its origins in Spain and southern France throughout Europe. It is called a killer slug, because it is so voracious that it even eats its own relatives. It reproduces easily and causes major problems in gardens and crops.

Photo: CarlosVdeHabsburgo-CC-BY-SA

Jellyfish without a ticket

The Australian spotted jellyfish is now found in large parts of the world. Its origin is in fact the ocean that surrounds Australia. But the jellyfish has accompanied the merchant ships in their ballast tanks. These are tanks that are filled with water for balance, when the ship has no cargo. When the ships are then loaded, the tanks are at times emptied into foreign waters. Then jellyfish and other organisms are released. The Australian spotted jellyfish can also be attached to the hull of ships and hitch-hike to other parts of the world. The jellyfish eats large amounts of plankton that the native species need to survive.

Australian spotted jellyfish

Phyllorhiza punctata

Slightly venomous

Jellyfish are so-called cnidarians, and are related to, for example, corals and anemones. All jellyfish have ”nettle cells” known as cnidocytes, and the Australian spotted jellyfish has long nettle cells with a weak venom. The venom is not dangerous to humans.

The Australian spotted jellyfish swims freely in the sea in large shoals, and prefers high salinity. The species can swim long distances, and a shoal can feed on large quantities of zooplankton in a limited area of the sea until it is entirely cleansed. When the jellyfish occasionally reach high numbers, other species may temporarily run out of food.

The jellyfish’s stinging cells are located in its tentacles.

Photo: Johannes-Maximilian-CC-BY-SA

Reproduces in two different ways

All jellyfish have a specific and rather complicated way of reproducing, with several different stages. When adult Australian spotted jellyfish are about to breed, the male ejects sperm through his mouth into the water, which the female in turn catches with her mouth. She filters the sperm down to her reproductive organ, where the eggs are fertilised.

When the larvae hatch, they leave the female’s body and continue their development on the seabed. They grow into so-called polyps. The polyps also reproduce, but in a different way than adult jellyfish. Polyps reproduce by division, where one polyp creates several copies of itself. The small copies swim freely in the water and eventually grow into large, adult jellyfish. This results in many more adult jellyfish than the polyps produced by the males and females.

Photo: Amada44-CC-BY

Hitchhiked by ships

The Australian spotted jellyfish has become an invasive species. Invasive means that a species has arrived in a place where it does not normally belong and is therefore causing damage. Species that are considered invasive are often quick to reproduce and have very few natural enemies. When polyps of the Australian spotted jellyfish have grown on the hulls of ships, the species has been able to spread across much of the world. The jellyfish has done great damage to wildlife in places like the Gulf of Mexico and the Mediterranean Sea.

Distribution worldwide

Australia and some tropical seas.

White marking = Distribution

Threat based on the Red List

Trade regulations

CITES: Not listed.

What is the Red List?

The Red List is a way to assess whether different animal and plant species are at risk of extinction based on criteria such as how many animals or plants of a species exist and how widely distributed they are. A national Red List assesses a species’ risk of dying out within national borders. The international Red List assesses a species’ risk of dying out worldwide.

Read more

About the Red List in Sweden: The Swedish Species Information Centre (Artdatabanken), www.artdatabanken.se/en/

About the Red List worldwide: The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), www.iucn.org

What is CITES?

CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) is a treaty that makes it illegal to buy or sell animals and plants that are at risk of extinction between countries without a permit.

CITES classifies species into different categories (called Appendix I, II and III) depending on how endangered each species is. In addition, the more the species is threatened by international trade, the higher its level of protection. Within the EU, CITES-listed species are further classified and protected by the EU’s own classification system. This has four Annexes, from A to D.

Photo: Steve-Hillebrand

Ban on trading wild-caught species

The highest protection against trade is given to CITES-listed species included in the EU’s Annexes A and B. Usually this means that trade between the EU and the rest of the world is illegal without a permit. There is also a ban on trading these species within the EU unless it can be proved that they have a lawful origin and were not caught in the wild.

It is also forbidden to use plants or animals to make souvenirs etc. Anyone who breaks these regulations can be fined or imprisoned.

Controlling the spread of species

CITES-listed species that are in the EU’s Annex C are classified as endangered in at least one country but not necessarily in the whole world. An Annex D classification means that individual members of a species may be imported to the extent that they do not need to be regulated to avoid any risk of them spreading uncontrollably where they do not belong.