Vad är metamorfos?

Många insekter, amfibier och ryggradslösa djur genomgår något som kallas metamorfos. Det betyder att djuret genomgår stora förändringar i utseendet från nyfödd till vuxen individ. Metamorfos brukar delas in i två kategorier – en som kallas fullständig metamorfos och en som kallas ofullständig metamorfos.

De flesta groddjur genomgår en fullständig metamorfos, från ägg...

Bild: Geoff-Gallice-CC-BY

..till yngel...

Bild: Benny-Mazur-CC-BY

...som så småningom får ben, förlorar sin svans och sina gälar...

Bild: Ellika-Nordström-Malmö-Museer

...och utvecklas till en vuxen groda.

Bild: Ellika-Nordström-Malmö-Museer

Insekters fullständiga metamorfos börjar med ett ägg...

Bild: Gilles-San-Martin-CC-BY-SA

...som kläcks till en larv...

Bild: Superdrac-CC-BY-SA

...som sedan förpuppas för den sista delen av förvandlingen.

Bild: hamon-jp_CC-BY-SA

Ut ur puppan kommer den vuxna insekten, där formen kallas imago. När vingarna vecklats ut...

Bild: Entomolo-CC-BY-SA

...är det sista stadiet klart i den fullständiga metamorfosen. På bilden syns en makaonfjäril.

Bild: Thomas-Bresson-CC-BY

Bin genomgår också fullständig metamorfos. Här syns både ägg och bilarver i en bikupa.

Bild: Waugsberg-CC-BY-SA

De olika stadierna i en puppa hos ett honungsbi.

Bild: Waugsberg-CC-BY-SA

Ett vuxet honungsbi efter metamorfosen från ägg, till larv, till puppa och färdigt bi.

Bild: Richard-Bartz-CC-BY-SA

Från ägg, till larv, till puppa, till vuxen

Fjärilar, flugor, myror, bin och grodor är exempel på djur som genomgår fullständig metamorfos. Hos insekter med fullständig metamorfos är stadierna fyra; från ägg, till larv, puppa och vuxen individ (som också kallas imago). Grodornas faser är lite annorlunda än insekternas. Larvstadiet för grodor kallas för grodyngel, och utvecklas vidare till halvvuxna grodor i stället för att förpuppas. Det gäller för de flesta av groddjuren.

Trollsländelarver kallas för nymfer, och är mer lika den vuxna trollsländan än vad till exempel fjärilslarver är lika den vuxna fjärilen.

Istället för att förpuppas ömsar trollsländenymfen skal flera gånger för att kunna växa. Här kommer en fullvuxen trollslända ut ur sitt förra skal.

Bild: L.-B.-Tettenborn-CC-BY-SA

Tvestjärtar genomgår också ofullständig metamorfos. Deras larver, eller nymfer, ser ut som små versioner av den vuxna tvestjärten.

Bild: Tom-Oates-CC-BY-SA

Ofullständig metamorfos hoppar över förpuppning

Trollsländor, tvestjärtar och bärfisar är exempel på insekter som inte förpuppas, utan förvandlas till vuxna individer genom att ömsa skinn. De hoppar helt enkelt över det tredje stadiet helt och hållet. Larverna ser i stället ut som små varianter av de vuxna individerna, och kallas för nymfer. Nymferna ömsar ibland skinn flera gånger innan de blir fullt utvecklade och könsmogna.

Axolotlen är en salamander som inte genomgår någon metamorfos. Andra salamanderyngel tappar sina gälar när de blir äldre, men axolotlen ser ut som ett yngel hela livet.

Bild: Johanna-Rylander-Malmö-Museer

Ett yngel av axolotl med samma krage av gälar som den kommer behålla som vuxen.

Bild: Orizatriz-CC-BY-SA

Xochimilcosjön, en av få platser där axolotlen finns i det vilda.

Bild: Juan-Manuel-Gomez-Ruano-CC-BY-SA

Den mindre vattensalamandern genomgår fullständig metamorfos och förlorar sina gälar som vuxen.

Bild: gailhampshire-CC-BY

Yngel hela livet

Axolotlen tillhör familjen salamandrar. Den är starkt utrotningshotad, och finns idag bara i några få vattendrag nära Mexico City. Axolotlen genomgår inte metamorfos som andra groddjur, utan förblir i yngelstadiet hela livet! Andra groddjur blir av med sina gälar när de utvecklas från yngel till vuxna, men axolotlen behåller sina gälar och sitt yngelutseende, livet ut.

Achoque

Ambystoma dumerilii

Utbredningen inte större än Kirseberg

I södra Mexiko, på nästan 2000 meters höjd över havet, ligger en sjö som heter Patzcuarosjön. Sjön är inte speciellt stor – om den hade legat i Sverige hade den varit ladets tjugonde största. Patzcuarosjön har vulkaniskt ursprung, och kring sjön ligger branta berg. I en liten del av sjön, inom ett område som inte är större än stadsdelen Kirseberg i Malmö, lever achoquen – en stor salamander med mycket märkliga egenskaper. På grund av miljöförstöring och jakt är achoquen akut utrotningshotad, bland annat till följd av skogsavverkning som fört med sig material som slammat igen delar av sjön.

Bild: AlejandroLinaresGarcia-CC-BY-SA

Yngel hela livet

Achoquen är, precis som sin mycket nära släkting axolotlen, en salamander som lever hela sitt liv med ett yngelutseende. De flesta groddjur – som salamandrar tillhör – genomgår en så kallad metamorfos från yngel till vuxen. Men inte alla! Achoquen ser likadan ut hela livet, med typiska yngellika gälar runt huvudet, och ett helt liv under vattenytan. Achoquen har också lungor, men de används sällan. Ibland simmar den upp till ytan och tar lite luft, men luften används främst för att styra salamanderns flytförmåga i vattnet. Syre tar achoquen upp från vattnet genom sina gälar. En annan märklig egenskap som delas mellan achoquen och axolotlen är förmågan att regenerera förlorade kroppsdelar! Till och med ett helt ben skulle kunna växa ut igen, om salamandern förlorade det.

Bild: Sebastian-Voitel-CC-BY-NC-SA

Bevaras av djurparker – och nunnor

När en art endast lever på en enda plats, kallas den för endemisk. Endemiska arter löper större risk än andra för att bli utrotningshotade, eftersom det inte finns några naturliga reserver eller spridningar av arten. Idag är achoquen extremt sällsynt i Patzcuarosjön, och miljöförstöringen i området är så stor att det ännu inte finns några möjligheter att plantera ut salamandrar uppfödda i akvariemiljö. Därför är det viktigt med bevarandeprojekt som syftar till att hålla arten vid liv och med friska gener, till dess att achoquens naturliga miljö återhämtat sig. De salamandrar som bor här på Akvariet, ingår i ett bevarandeprogram under ledning av organisationen Citizen Conservation.

Men ett annat slags bevarandearbete för achoquen bedrivs också på plats i Mexiko. En grupp nunnor från Dominikanorden har under många år använt achoquen till att tillverka en slags hostmedicin. När nunnorna upptäckte att antalet achoques minskade rejält i slutet på 1900-talet, bestämde man sig för att börja föda upp dem i egen regi. Idag finns omkring 300 salamandrar i akvarier i det lokala klostret i Patzcuaro, och nunnornas bevarandearbete har varit – och är – mycket viktigt för att fortsätta hålla liv i arten.

Bild: Sebastian-Voitel-CC-BY-NC-SA

Utbredningsområde i världen

Patzcuarosjön, södra Mexiko.

Hotstatus enligt Rödlistan

Reglerad inom handel

CITES: B-listad.

Tequilatandkarp

Zoogoneticus tequila

Den lilla fisken som dog ut i naturen

I slutet av 1990-talet trodde man att tequilatandkarpen var helt utdöd i det vilda. Några år senare, 2001, hittades en liten grupp tequilatandkarpar i en liten pöl i närheten av den flod där de en gång i tiden fanns i stora mängder. Två år senare var pölen, och därför också arten, helt borta från naturen! Att det blivit utrotad berodde på miljöförstöring i området, men också på att invasiva fiskarter hade konkurrerat ut tequilatandkarpen.

Bild: Cedricguppy-Loury-Cedric-CC-BY-SA

Lyckad återkomst

Men den lilla fisken var inte borta för alltid. I akvarier runt om i världen fanns tequilatandkarpar, som levt och förökat sig sedan 1950-talet när de först kom in i akvariehobbyn. En liten grupp på 10 tequilatandkarpar skickades från England till ett universitet i Mexiko, där man bestämt sig för att försöka återinföra den lilla fisken till naturen igen.

Projektet tog många år. Fiskarna studerades noggrant, för att man skulle få veta precis hur de levde och vad de behövde för att klara sig. Så småningom fick fiskarna flytta ut i en gammal pool, och öva sig på att leva i det vilda – med varierande vattenförhållanden, olika tillgång på mat och vissa rovfiskar. År 2016 kunde man till slut släppa ut 80 tequilatandkarpar i sin orginalmiljö i Teuchitlánfloden. Tre år senare, 2019, kunde forskarna konstatera att arten verkar må bra, äta och föröka sig som den ska i naturen.

Bild: Cedricguppy-Loury-Cedric-CC-BY-SA

Endemisk för Mexiko

Det mesta vi idag vet om tequilatandkarpen är sådant som forskare lärt sig av att ha fött upp arten i fångenskap. Arten är endemisk för området kring Teuchitlánfloden nära Guadalajara i Mexiko, och lever i rinnande vatten eller små pölar med grunt vatten. Än är det inte säkert att arten kommer klara sig på sikt, och den räknas därför som hotad enligt Rödlistan.

Utbredningsområde i världen

Teuchitlánfloden i centrala Mexico.

Hotstatus enligt Rödlistan

Reglerad inom handel

CITES: Ej listad.

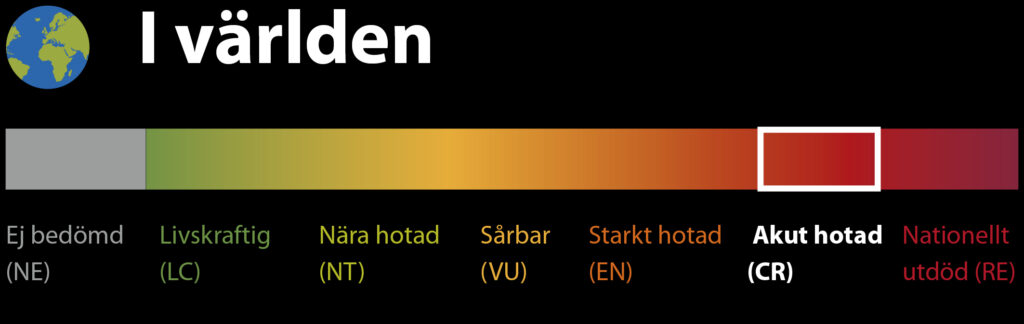

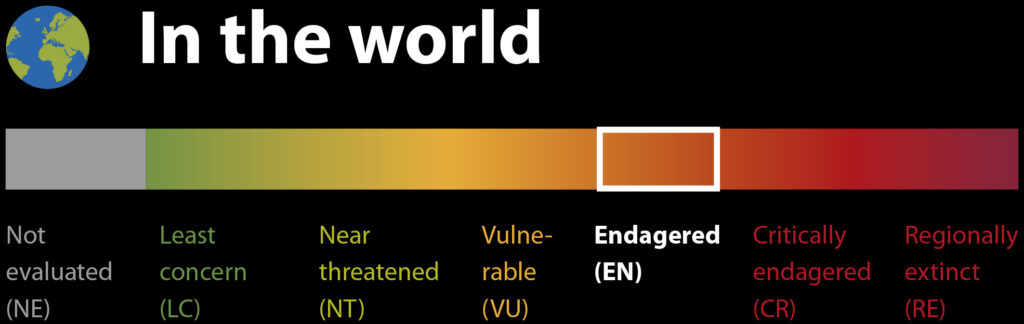

Vad är Rödlistan?

Rödlistning är ett sätt att bedöma om olika djur- och växtarter är utrotningshotade utifrån kriterier som hur många djur eller växter som finns av arten och hur utbredda de är. En nationell rödlistning bedömer artens risk att dö ut inom ett lands gränser. Den internationella rödlistningen bedömer artens risk att dö ut över hela jorden.

Läs mer

Om rödlistning i Sverige: Artdatabanken, www.artdatabanken.se

Om rödlistning i världen: International Union for Conservation of Nature, IUCN, www.iucn.org

Vad är CITES?

För att bekämpa olaglig handel med djur och växter finns en internationell överenskommelse om handel, som heter CITES. CITES innebär att utrotningshotade djur och växter inte får köpas eller säljas mellan olika länder utan tillstånd.

CITES klassar olika arter i olika kategorier (som kallas Appendix I, II och III) beroende på hur hotad arten är. Ju större hotet från handeln är desto högre skydd. Inom EU finns ytterligare skydd för arter i CITES. EU:s egen klassning har fyra steg: A-D.

Bild: Steve-Hillebrand

Förbjudet att handla med viltfångade arter

Högst skydd mot handel har de arter som är inom kategori A och B. Här gäller oftast att handel mellan EU och övriga världen är förbjuden utan tillstånd. Arter som är CITES A eller B-klassade får inte heller köpas eller säljas inom EU om det inte kan bevisas att de har lagligt ursprung och inte fångats i det vilda.

Att använda växter eller djur för att tillverka souvenirer och annat är också förbjudet. Den som bryter mot reglerna kan dömas till böter eller fängelse.

Kontrollera spridning av arter

Arter som är CITES C-klassade är utrotningshotade i ett visst land men inte nödvändigtvis i hela världen. CITES D-klassning betyder att en art importeras i så stort antal att de behöver regleras för att inte riskera att sprida sig okontrollerat där de inte hör hemma.

What is metamorphosis?

Many insects, amphibians and invertebrates undergo something called metamorphosis. This means that the animal undergoes major changes in appearance from newborn to adult. Metamorphosis is usually divided into two categories – one called complete metamorphosis and the other called incomplete metamorphosis.

Most amphibians go trough complete metamorphosis, from an egg...

Photo: Geoff-Gallice-CC-BY

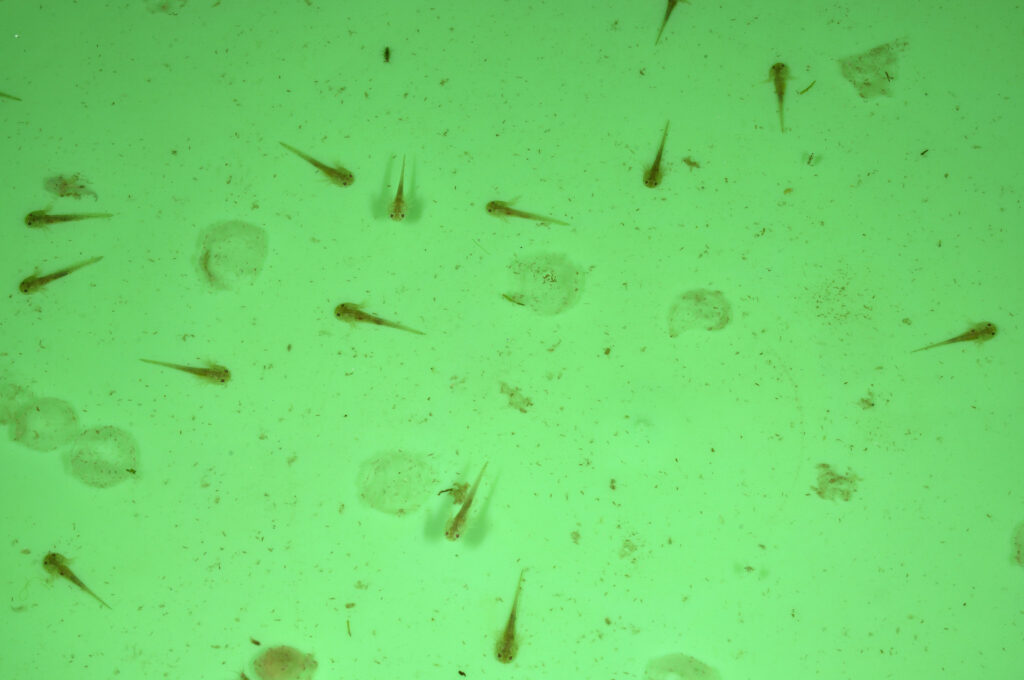

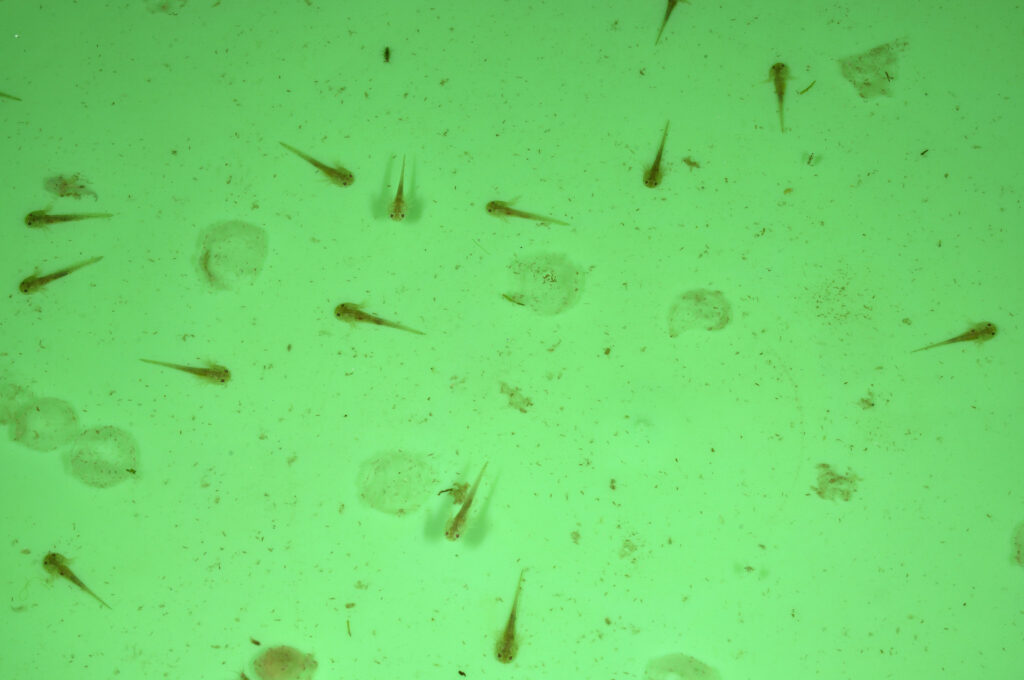

...to tadpole...

Photo: Benny-Mazur-CC-BY

...that eventually gets legs, looses its tail and gills...

Photo: Ellika-Nordström-Malmö-Museer

...and grows into an adult frog.

Photo: Ellika-Nordström-Malmö-Museer

The complete metamorphosis in insects starts with an egg...

Photo: Gilles-San-Martin-CC-BY-SA

...that hatch into a caterpillar...

Photo: Superdrac-CC-BY-SA

...that pupates for the last stage of the transformation.

Photo: hamon-jp_CC-BY-SA

The adult insect, called imago, emerges from the pupa. When the wings unfold...

Photo: Entomolo-CC-BY-SA

...the last stage of the complete metamorphosis is finished. The photo shows a common yellow swallowtail.

Photo: Thomas-Bresson-CC-BY

Bees also go through complete metamorphosis. The photo shows eggs and larvae in a bee hive.

Photo: Waugsberg-CC-BY-SA

The different stages in a honey bee pupa.

Photo: Waugsberg-CC-BY-SA

An adult honey bee after the metamorphosis from egg, to larva, to pupa to this stage.

Photo: Richard-Bartz-CC-BY-SA

From egg, to larva, to pupa, to adult

Butterflies, flies, ants, bees and frogs are examples of animals that undergo complete metamorphosis. In insects with complete metamorphosis, the stages are four; from egg, to larva, to pupa and finally adult (also called imago). The stages of frogs are slightly different from those of insects. The larval stage of frogs is called tadpole, and develops into semi-adult frogs rather than pupating. This is true for most of the amphibians.

Dragonfly larvae are called nymphs, and look more like the adult dragonfly than for example a caterpillar resembles its butterfly adult form.

Insted of pupating, the dragonfly nymph molts several times to grow. This photo shows an adult dragonfly emerging from its old skin.

Photo: L.-B.-Tettenborn-CC-BY-SA

Earwigs also go through incomplete metamorphosis. Their larvae, called nymphs, look like tiny versions of adult earwigs.

Photo: Tom-Oates-CC-BY-SA

Incomplete metamorphosis skips pupation

Dragonflies, earwigs and stink bugs are examples of insects that do not pupate, but turn into adults by moulting. They simply skip the third stage altogether. Instead, the larvae look like small versions of the adults, and are called nymphs. Nymphs sometimes shed their skins several times before becoming fully developed and sexually mature.

The axolotl is a salamander that doesn't go through metamorphosis. Other salamander tadpole loose their gills when getting older, but the axolotl looks like a tadpole all its life.

Photo: Johanna-Rylander-Malmö-Museer

An axolotl tadpole with the same gills around its head, as it will keep as an adult.

Photo: Orizatriz-CC-BY-SA

Lake Xochimilco, one of very few places where axolotls live in the wild.

Photo: Juan-Manuel-Gomez-Ruano-CC-BY-SA

The smooth newt goes through complete metamorphosis and looses its gills as an adult.

Photo: gailhampshire-CC-BY

Larva for life

The axolotl belongs to the salamander family. It is highly endangered, and is now found only in a few streams near Mexico City. The axolotl does not undergo metamorphosis like other amphibians, but remains in the larval, juvenile stage throughout its life! Other amphibians lose their gills as they develop from larva to adults, but the axolotl retains its gills and larval appearance for its entire life.

Achoque

Ambystoma dumerilii

Distribution no larger than Kirseberg

In Southern Mexico, at an altitude of almost 2000 metres above sea level, there is a lake called Lake Patzcuaro. The lake is not particularly large – if it had been in Sweden, it would have come in as number twenty in size in the country. Lake Patzcuaro has volcanic origins, and around the lake are steep mountains. In a small part of the lake, in an area no larger than the district of Kirseberg in Malmö, lives the achoque – a large salamander with very strange abilities. Due to environmental degradation and hunting, the achoque is critically endangered, partly as a result of deforestation that has brought with it material that has silted up parts of the lake.

Photo: AlejandroLinaresGarcia-CC-BY-SA

Tadpole throughout their lives

The achoque, like the very close relative the axolotl, is a salamander that lives its entire life looking like a tadpole. Most amphibians – to which salamanders belong – undergo a so-called metamorphosis from larva to adult. But not all of them! The achoque looks the same throughout its life, with typical larva-like gills around its head, and it lives its whole life below the surface of the water. The achoque also has lungs, but they are rarely used. Sometimes it swims up to the surface and takes in some air, but the air is mainly used to control the salamander’s buoyancy in the water. The achoque absorbs oxygen from the water through its gills. Another peculiar trait shared between the achoque and the axolotl is the ability to regenerate lost body parts! Even a whole leg can grow back, if the salamander loses it.

Photo: Sebastian-Voitel-CC-BY-NC-SA

Preserved by zoos – and nuns

When a species lives in only one place, it is called endemic. Endemic species are at greater risk than others of becoming endangered, as there are no natural reserves or dispersals of the species. Today, the achoque is extremely rare in Lake Patzcuaro, and the environmental degradation in the area is so great that there are still no opportunities to set out salamanders bred in aquarium environments. Therefore, conservation projects aimed at keeping the species alive and their genes healthy, until the natural environment of the achoque recovers, are important. The salamanders that live here at the Aquarium are part of a conservation program led by the organisation Citizen Conservation.

But another kind of conservation work for the achoque is also being carried out on site in Mexico. A group of nuns from the Dominican Order have been using the achoque for many years to make a kind of cough medicine. When the nuns discovered that the number of achoques had decreased significantly in the late 1900s, they decided to start breeding them themselves. Today, there are about 300 salamanders in aquariums in the local convent in Patzcuaro, and the nuns’ conservation work has been – and is – very important to keep the species alive.

Photo: Sebastian-Voitel-CC-BY-NC-SA

Distribution worldwide

Lake Patzcuaro, southern Mexico.

Threat based on the Red List

Trade regulations

CITES: B-listed.

Tequila splitfin

Zoogoneticus tequila

The little fish that went extinct in the wild

At the end of the 1990s, the tequila splitfin was thought to be completely extinct in the wild. A few years later, in 2001, a small group of tequila splitfins were found in a small puddle near the river where they were once abundant. Two years later, the puddle, and therefore the entire species, had disappeared from the wild! Its extinction was due to pollution in the area, but also due to invasive fish species that had outcompeted the tequila splitfin.

Photo: Cedricguppy-Loury-Cedric-CC-BY-SA

Successful return

But the little fish wasn’t gone forever. In aquariums around the world, tequila splitfins had been living and breeding since the 1950s when they first became a popular aquarium fish. A small group of 10 tequila splitfins were sent from England to a university in Mexico, where it was decided to try to reintroduce the little fish back into the wild.

The project took many years. The fish were carefully studied in order to find out exactly how they lived and what they needed to survive. Eventually, the fish were moved into an old pool, and got to practice living in the wild – with varying water conditions, different food availability and the presence some predatory fish. In 2016, 80 pairs of tequila splitfins were finally released into their original habitat in the Teuchitlán River. Three years later, in 2019, researchers found that the species appears to be thriving, feeding and reproducing well in the wild.

Photo: Cedricguppy-Loury-Cedric-CC-BY-SA

Endemic to Mexico

Most of what we know today about the tequila splitfin is what scientists have learned from breeding the species in captivity. The species is endemic to the Teuchitlán River area near Guadalajara, Mexico, where it lives in flowing water or small puddles of shallow water. It is not yet certain that the species will survive in the long run, and is therefore listed as endangered on the Red List.

Distribution worldwide

The Teuchitlán River in central Mexico.

Threat based on the Red List

Trade regulations

CITES: Not listed.

What is the Red List?

The Red List is a way to assess whether different animal and plant species are at risk of extinction based on criteria such as how many animals or plants of a species exist and how widely distributed they are. A national Red List assesses a species’ risk of dying out within national borders. The international Red List assesses a species’ risk of dying out worldwide.

Read more

About the Red List in Sweden: The Swedish Species Information Centre (Artdatabanken), www.artdatabanken.se/en/

About the Red List worldwide: The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), www.iucn.org

What is CITES?

CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) is a treaty that makes it illegal to buy or sell animals and plants that are at risk of extinction between countries without a permit.

CITES classifies species into different categories (called Appendix I, II and III) depending on how endangered each species is. In addition, the more the species is threatened by international trade, the higher its level of protection. Within the EU, CITES-listed species are further classified and protected by the EU’s own classification system. This has four Annexes, from A to D.

Photo: Steve-Hillebrand

Ban on trading wild-caught species

The highest protection against trade is given to CITES-listed species included in the EU’s Annexes A and B. Usually this means that trade between the EU and the rest of the world is illegal without a permit. There is also a ban on trading these species within the EU unless it can be proved that they have a lawful origin and were not caught in the wild.

It is also forbidden to use plants or animals to make souvenirs etc. Anyone who breaks these regulations can be fined or imprisoned.

Controlling the spread of species

CITES-listed species that are in the EU’s Annex C are classified as endangered in at least one country but not necessarily in the whole world. An Annex D classification means that individual members of a species may be imported to the extent that they do not need to be regulated to avoid any risk of them spreading uncontrollably where they do not belong.