När en art blir flera – divergent evolution

Evolution är grunden till mångfalden av arter på jorden. Egentligen är all evolution resultatet av slumpmässiga genetiska mutationer – där vissa ger så stor fördel för individen att sannolikheten ökar att den individen ska kunna föröka sig. Det kan vara simhud, större näbb, förmåga att simma på stora djup, eller en slank kropp som kan klättra bättre i träd.

En typ av evolution kallas för divergent evolution. Det är när nära besläktade arter över tiden anpassar sig till helt olika miljöer, och därför utvecklar helt olika egenskaper – trots att de delar ursprung. Kan du komma på några djur som är släkt, men ser väldigt olika ut?

Hunddjuren har en gemensam anfader, men har utvecklats till många olika arter med olika utseenden och nischer.

Bild: Profberger-CC-BY-SA

Kattdjuren har också ett gemensamt ursprung - men utvecklingen till olika arter har gett dem många olika levnadssätt.

Bild: LittleJerry-CC-BY-SA

Tillräckligt långt tillbaka i tiden har alla ryggradsdjur ett gemensamt ursprung. Bilden visar hur ben i frambenen hos människa, hund, fåglar och valar har samma ursprung men utvecklats till olika funktioner.

Bild: Volkov-Vladislav-Petrovich-CC-BY-SA

Inom gruppen grodor finns en stor variation i färg, form och levnadssätt - något som utvecklats genom divergent evolution.

Bild: Termininja-CC-BY-SA

Mammutar och elefanter har ett gemensamt ursprung, men genom divergent evolution fick de olika levnadssätt och utseenden.

Bild: Mauricio-Anton-CC-BY, Bernard-DUPONT-CC-BY-SA

Darwins finkar som flyttade över havet

Darwins finkar kallas en grupp fåglar som lever på Galapagosöarna, utanför kusten av Ecuador. Egentligen är fåglarna inte riktiga finkar, utan tillhör en grupp som kallas tangaror. Charles Darwin, den berömda vetenskapsmannen som utvecklade evolutionsteorin, studerade dessa fåglar under sin resa på öarna under 1800-talet. Han märkte att finkarna hade olika former på näbbarna, beroende på vilken typ av mat de åt. Till exempel var finkar med långa, spetsiga näbbar bättre lämpade för att fånga insekter, medan finkar med korta, grova näbbar var bättre lämpade för att knäcka frön. Senare har forskare förklarat att Darwins finkar alla härstammar från en enda fågelart, som tog sig över havet till Galapagosöarna för ungefär 2 miljoner år sedan.

Över tiden spred fåglarna ut sig över öarna, och de olika grupperna utvecklade olika nischer – alltså sätt att leva – och blev så småningom flera olika arter. Detta är ett exempel på divergent evolution, eftersom finkar med olika näbbformer utvecklades från en gemensam förfader. Idag finns 18 arter av Galapagosfinkar beskrivna.

Gruppen av fåglar som kallas Darwins finkar, har utvecklats till olika arter genom divergent evolution, men har ett gemensamt ursprung. Tydligast syns skillnaderna i de olika stora näbbarna.

Bild: Kiwi-Rex-CC-BY-SA

I Malawisjön i Afrika, finns ungefär 700 olika arter av ciklider, som alla har ett gemensamt ursprung. De många olika nischerna som finns i sjön, har lett till att olika fiskgrupper kunnat anpassa sig på väldigt olika sätt.

Bild: platours_flickr-CC-BY-NC-ND

Hundratals olika malawiciklider

Afrikanska ciklider är en grupp fiskar som lever i sötvattenssjöar i Afrika. Det finns många olika arter av ciklider, och de kommer i en stor variation av former, storlekar och färger. Cikliderna har utvecklats för att fylla många olika ekologiska nischer i sjöarna. Vissa är anpassade för att äta alger, medan andra äter andra fiskar. Vissa lever vid strandkanten, och andra på stora djup.

Malawisjön är den sjö som har flest olika ciklider. 700 arter är beskrivna, men det finns troligtvis upp till 1000, och de är nära släkt. Genom årmiljoner har Malawisjöns vattennivå både höjts och sänkts, och det har skapat många nya nischer – som i sin tur lett till nya arter. När ciklidpopulationerna utvecklades över tid, fick de olika anpassningar som lät dem specialisera sig på olika sorters mat. Till exempel har vissa ciklider vassa tänder för att fånga och äta andra fiskar, medan andra har platta tänder för att skrapa alger från stenar.

Bilder: Derek Keats-Vengolis-James Reardon-psyberartist-Christopher Watson-Donald Hobern-James Jolokia-Hectonichus-Charles J. Sharp-Bernard DUPONT-Sheba_Also-John Tann-CC-BY-SA

Varanernas gemensamma ursprung

Varaner är en grupp ödlor som lever i Afrika, Asien och Oceanien. Det finns många arter av varaner, men alla tillhör samma släkte. Trots att varanerna är nära släkt med varandra, är de väldigt olika i storlek, form och levnadssätt. Den minsta varanarten blir ungefär 20 cm lång, medan komodovaranen, varanernas bjässe, blir upp mot tre meter lång! Vissa varaner är anpassade för att klättra i träd, medan andra lever på marken. Det finns också varaner som delvis lever i vattnet!

Olika livsstilar har lett till olika anpassningar hos varanerna. Trädlevande varaner har långa, smala kroppar och svansar som kan gripa eller hålla balansen när ödlan klättrar. Marklevande varaner har kraftiga kroppar och starka ben för att springa på marken.

Mitchells vattenvaran

Varanus mitchelli

En av de minsta varanerna

Mitchells vattenvaran är en liten varanart som lever i fuktiga tropiska områden i norra Australien. Gruppen varaner är väldigt varierad i storlek och levnadsätt hos arterna. Den största arten, komodovaran, kan bli tre meter lång och väga över hundra kilo, medan de minsta arterna inte blir mycket längre än 20 cm och väger strax under 20 gram. Mitchells vattenvaran tillhör bland de minsta nu levande varanerna.

I norra Australien är klimatet tropiskt, och mitchells vattenvaran trivs i träskmarker, deltaområden och laguner. Ödlan spenderar största delen av sitt liv på land, men är en duktig simmare. När vattennivån är hög, äter mitchells vattenvaran en stor andel fisk och groddjur. Under torrare perioder äter arten mer landlevande djur som insekter, fågelungar och ibland små däggdjur.

Bild: Graham-Winterflood-CC-BY-SA

Hotad av en invasiv padda

Mitchells vattenvaran är listad som kritiskt hotad på IUCN:s rödlista. Det är sista hotnivån innan en art räknas som utdöd i det vilda. Det finns flera olika hot mot varanen, men det största kommer från ett kanske lite oväntat håll: en padda! I Australien finns en invasiv art av padda som heter agapadda. Den planterades in i landet av människor, för att man hoppades att den skulle äta skadeinsekter från odlingar. Vad man inte tänkte på, var att paddan inte har några naturliga fiender i Australien – och paddan är extremt giftig. Att äta en fullvuxen padda leder till en säker död för mitchells vattenvaran och många andra varanarter.

Bild: Bernard-DUPONT-CC-BY-NC-SA

Kan man träna en varan?

Under 2010-talet har agapaddan spritt sig ännu mer över samma utbredningsområde som mitchells vattenvaran, och man räknar med att spridningen av agapaddan inte går att stoppa. Istället sker forskning för att se om det går att lära varaner att inte äta agapaddor. Man hoppas att om varaner får äta unga agapaddor, som inte innehåller en dödlig mängd gift, ska de lära sig att förknippa agapaddan med obehag och därför undvika att äta dem igen. Det verkar svårt – men inte omöjligt. Men tills problemet med agapaddan i Australien är under kontroll är det mycket viktigt att arter som mitchells vattenvaran hålls i bevarandeprogram, för att arten inte ska riskera att helt gå förlorad.

Utbredningsområde i världen

Norra Australien.

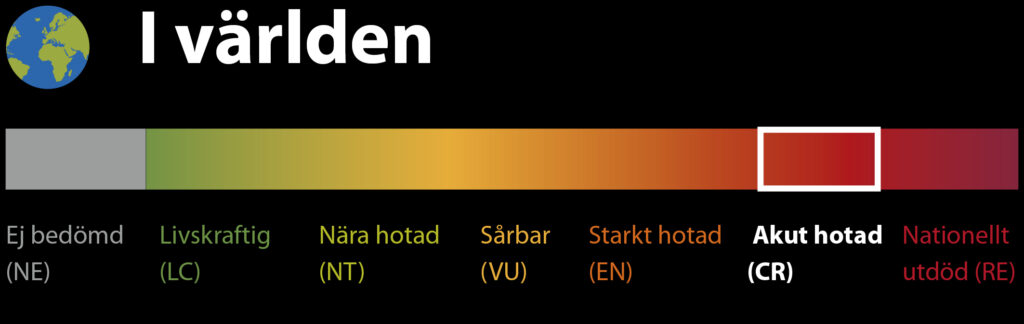

Hotstatus enligt Rödlistan

Reglerad inom handel

CITES: B-listad.

Vad är Rödlistan?

Rödlistning är ett sätt att bedöma om olika djur- och växtarter är utrotningshotade utifrån kriterier som hur många djur eller växter som finns av arten och hur utbredda de är. En nationell rödlistning bedömer artens risk att dö ut inom ett lands gränser. Den internationella rödlistningen bedömer artens risk att dö ut över hela jorden.

Läs mer

Om rödlistning i Sverige: Artdatabanken, www.artdatabanken.se

Om rödlistning i världen: International Union for Conservation of Nature, IUCN, www.iucn.org

Vad är CITES?

För att bekämpa olaglig handel med djur och växter finns en internationell överenskommelse om handel, som heter CITES. CITES innebär att utrotningshotade djur och växter inte får köpas eller säljas mellan olika länder utan tillstånd.

CITES klassar olika arter i olika kategorier (som kallas Appendix I, II och III) beroende på hur hotad arten är. Ju större hotet från handeln är desto högre skydd. Inom EU finns ytterligare skydd för arter i CITES. EU:s egen klassning har fyra steg: A-D.

Bild: Steve-Hillebrand

Förbjudet att handla med viltfångade arter

Högst skydd mot handel har de arter som är inom kategori A och B. Här gäller oftast att handel mellan EU och övriga världen är förbjuden utan tillstånd. Arter som är CITES A eller B-klassade får inte heller köpas eller säljas inom EU om det inte kan bevisas att de har lagligt ursprung och inte fångats i det vilda.

Att använda växter eller djur för att tillverka souvenirer och annat är också förbjudet. Den som bryter mot reglerna kan dömas till böter eller fängelse.

Kontrollera spridning av arter

Arter som är CITES C-klassade är utrotningshotade i ett visst land men inte nödvändigtvis i hela världen. CITES D-klassning betyder att en art importeras i så stort antal att de behöver regleras för att inte riskera att sprida sig okontrollerat där de inte hör hemma.

When one species becomes several – divergent evolution

Evolution is the basis of the diversity of species on Earth. All evolution is actually the result of random genetic mutations – some of which confer such a great advantage on the individual that it increases the likelihood that that individual will be able to reproduce. It can be webbed skin, a larger beak, the ability to swim at great depths, or a slender body that can climb trees better.

One type of evolution is called divergent evolution. This is when closely related species adapt to completely different environments over time, and therefore develop completely different traits – despite the fact that they share origins. Can you think of any animals that are related, but look very different?

The canids - or dog-like animals - share a common ancestor, but have evolved into many different species with various appearances and niches.

Photo: Profberger-CC-BY-SA

The felids - or cat-like animals - also share a common origin, but the evolution into different species has provided them with various lifestyles.

Photo: LittleJerry-CC-BY-SA

Long ago, all vertebrates share a common origin. The image illustrates how bones in the forelimbs of humans, dogs, birds, and whales have the same origin but evolved into different functions.

Photo: Volkov-Vladislav-Petrovich-CC-BY-SA

Within the group of frogs, there is a wide variation in color, form, and lifestyles – something that has evolved through divergent evolution.

Photo: Termininja-CC-BY-SA

Mammoths and elephants share a common origin, but through divergent evolution, they acquired different lifestyles and appearances.

Photo: Mauricio-Anton-CC-BY, Bernard-DUPONT-CC-BY-SA

Darwin’s finches that moved across the ocean

Darwin’s finches are a group of birds that live on the Galapagos Islands, off the coast of Ecuador. The birds are in fact not true finches, but belong to a family called tanager. Charles Darwin, the famous scientist who developed the theory of evolution, studied these birds during his journey to the islands in the 1800s. He noticed that the finches had different beak shapes, depending on the type of food they ate. For example, finches with long, pointed beaks were better suited for catching insects, while finches with short, coarse beaks were better suited for cracking seeds. Later, scientists have explained that Darwin’s finches all descended from a single species of bird, which made its way across the ocean to the Galapagos Islands about 2 million years ago.

Over time, the birds spread out across the islands, and the different groups developed different niches – that is, ways of life – and eventually became several different species. This is an example of divergent evolution, as finches with different beak shapes evolved from a common ancestor. Today, 18 species of Galapagos finches have been described.

The group of birds known as Darwin's finches has evolved into different species through divergent evolution but shares a common origin. The most notable differences can be seen in their various beak sizes.

Photo: Kiwi-Rex-CC-BY-SA

In Lake Malawi in Africa, there are approximately 700 different species of cichlids, all of which have a common origin. The diverse niches present in the lake have led to various fish groups adapting in very different ways.

Photo: platours_flickr-CC-BY-NC-ND

Hundreds of different Malawi cichlids

African cichlids are a group of fish that live in freshwater lakes in Africa. There are many different species of cichlids, and they have a wide variety of shapes, sizes, and colours. The cichlids have developed to fill many different ecological niches in the lakes. Some are adapted to eating algae, while others eat other fish. Some live at the edge of the beach, and others at great depths.

Lake Malawi is the lake with the most different cichlids. 700 species are described, but there are probably up to 1000, and they are closely related. Over millions of years, Lake Malawi’s water level has both risen and fallen, and this has created many new niches – which in turn have led to new species. As cichlid populations evolved over time, they developed different adaptations that allowed them to specialise in eating different types of food. For example, some cichlids have sharp teeth for catching and eating other fish, while others have flat teeth for scraping algae from rocks.

Photos: Derek Keats-Vengolis-James Reardon-psyberartist-Christopher Watson-Donald Hobern-James Jolokia-Hectonichus-Charles J. Sharp-Bernard DUPONT-Sheba_Also-John Tann-CC-BY-SA

Common origin of the monitor lizards

Monitor lizards are a group of lizards that live in Africa, Asia, and Oceania. There are many species of monitor lizards, but they all belong to the same genus. Although the monitor lizards are closely related to each other, they are very different in size, shape and way of life. The smallest monitor lizard grows to about 20 cm in length, while the Komodo dragon, the giant of the monitor lizard, grows up to three meters long! Some monitor lizards are adapted to climbing trees, while others live on the ground. There are also monitor lizards that live partly in the water!

Different lifestyles have led to different adaptations in the monitor lizards. Arboreal monitor lizards have long, slender bodies and tails that can grasp or keep their balance as the lizard climbs. Ground-dwelling monitor lizards have stout bodies and strong legs for running on the ground.

Mitchell’s Water Monitor

Varanus mitchelli

One of the smallest monitor lizards

Mitchell’s water monitor is a small species of monitor lizards that lives in humid tropical areas of Northern Australia. The monitor lizard species are very varied in size and habitat. The largest species, the Komodo dragon, can grow to three meters in length and weigh over a hundred kilograms, while the smallest species do not grow much longer than 20 cm and weigh just under 20 grams. Mitchell’s water monitor is one of the smallest living monitor lizards.

In northern Australia, the climate is tropical, and Mitchell’s water monitor thrives in swamps, deltas, and lagoons. The lizard spends most of its life on land, but is a good swimmer. When the water level is high, Mitchell’s water monitors eat a large proportion of fish and amphibians. During drier periods, the species eats more terrestrial animals such as insects, young birds, and sometimes small mammals.

Photo: Graham-Winterflood-CC-BY-SA

Threatened by an invasive toad

Mitchell’s water monitor is listed as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List. This is the highest threat level before a species is considered extinct in the wild. There are several different threats to the lizard, but the biggest one comes from a perhaps unexpected direction: a toad! In Australia, there is an invasive species of toad called the cane toad. It was introduced into the country by humans, in the hope that it would eat insect pests from crops. What they did not think about was that the toad has no natural enemies in Australia – and that the toad is extremely poisonous. Eating a full-grown toad causes certain death for the Mitchell’s water monitor, and many other monitor lizard species.

Photo: Bernard-DUPONT-CC-BY-NC-SA

Can you train a monitor lizard?

During the 2010s, the cane toad has spread even more widely over the same distribution area as the Mitchell’s water monitor, and it is estimated that the spread of the cane toad cannot be stopped. Instead, research is being conducted to see if it is possible to teach monitor lizards not to eat cane toads. It is hoped that if monitor lizards are allowed to eat young toads, which do not contain a lethal amount of toxin, they will learn to associate the cane toad with discomfort and therefore avoid eating them again. It seems difficult – but not impossible. However, until the problem of the cane toad in Australia is brought under control, it is vital that species such as the Mitchell’s water monitor are kept in conservation programmes, so that the species is not at risk of going completely extinct.

Distribution worldwide

Northern Australia.

Threat based on the Red List

Trade regulations

CITES: B-listed.

What is the Red List?

The Red List is a way to assess whether different animal and plant species are at risk of extinction based on criteria such as how many animals or plants of a species exist and how widely distributed they are. A national Red List assesses a species’ risk of dying out within national borders. The international Red List assesses a species’ risk of dying out worldwide.

Read more

About the Red List in Sweden: The Swedish Species Information Centre (Artdatabanken), www.artdatabanken.se/en/

About the Red List worldwide: The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), www.iucn.org

What is CITES?

CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) is a treaty that makes it illegal to buy or sell animals and plants that are at risk of extinction between countries without a permit.

CITES classifies species into different categories (called Appendix I, II and III) depending on how endangered each species is. In addition, the more the species is threatened by international trade, the higher its level of protection. Within the EU, CITES-listed species are further classified and protected by the EU’s own classification system. This has four Annexes, from A to D.

Photo: Steve-Hillebrand

Ban on trading wild-caught species

The highest protection against trade is given to CITES-listed species included in the EU’s Annexes A and B. Usually this means that trade between the EU and the rest of the world is illegal without a permit. There is also a ban on trading these species within the EU unless it can be proved that they have a lawful origin and were not caught in the wild.

It is also forbidden to use plants or animals to make souvenirs etc. Anyone who breaks these regulations can be fined or imprisoned.

Controlling the spread of species

CITES-listed species that are in the EU’s Annex C are classified as endangered in at least one country but not necessarily in the whole world. An Annex D classification means that individual members of a species may be imported to the extent that they do not need to be regulated to avoid any risk of them spreading uncontrollably where they do not belong.