Vad är mimikry?

I naturen är konkurrensen om livsutrymmet hård och farorna är många. För att skydda sig använder djur och växter sig ibland av det som kallas för mimikry. Det betyder att de härmar utseende eller beteende hos farliga eller giftiga arter för att skrämma bort rovdjur och undvika att bli uppätna.

Mimikry är vanligt förekommande i naturen och kan ske på många olika sätt. Det finns två olika sorters mimikry, de kallas ”defensiv” och ”aggressiv”. Defensiv mimikry handlar om att skydda sig från att bli uppäten. Aggressiv mimikry är ovanligare, och handlar om att likna något ofarligt för att komma närmare sitt byte.

Olika sorters blomflugor som alla liknar bin eller getingar.

Bild: Alvesgaspar-CC-BY-SA

En blomfluga som liknar en humla.

Bild: Bruce-Marlin-CC-BY-SA

Tigerblomflugan liknar inte bara en geting med den gulsvarta teckningen, utan använder också frambenen för att likna getingens antenner.

Bild: Bruce-Marlin-CC-BY-SA

På bilden syns en vanlig geting. Den har tjocka antenner som blomflugor saknar, men tigerblomflugan försöker efterlikna med sina framben.

Bild: Bruce-Marlin-CC-BY-SA

Blomflugor liknar getingar

Ett exempel på defensiv mimikry kan vi se hos blomflugan. Blomflugan är en vanlig insekt i Sverige och det finns många olika sorters blomflugor. Blomflugan är en ofarlig nektar- och pollenätande insekt, men den härmar den giftiga och farliga getingens utseende för att lura rovdjur som annars skulle kunna äta upp dem. Blomflugans svarta och gula ränder påminner om getingens ränder i samma färger. En del blomflugor är lite hårigare och påminner mer om humlor.

Mjölksnoken, som lever i Nord- och Sydamerika härmar utseendet på de giftiga korallormarna för att undkomma fiender. Men att härma en annan art för bra kan vara farligt och motverka sitt syfte. Ibland slår människor ihjäl både mjölksnokar och blomflugor för att de liknar de farliga originalen.

Mjölksnoken är helt ofarlig, men ändå slår människor ihjäl många mjölksnokar av rädsla varje år. Det beror på att den har en färgteckning som är förvillande lik...

Bild: Johanna-Rylander-Malmö-Museer

...färgteckningen hos flera arter av giftiga korallormar, som till exempel Browns korallorm på bilden.

Bild: Daniel-Pineda-Vera-CC-BY

Arten föränderlig bläckfisk kan härma många olika farliga djur i havet, till exempel drakfiskar, havsormar och giftiga rockor.

Bild: Silke-Baron-CC-BY

Spindlar som luktar som myggor

Aggressiv mimikry kan också se ut på olika vis. Rovdjur kan härma sina bytesdjur för att komma närmare sitt byte. Det finns spindlar som släpper ut doftämnen (feromoner) som efterliknar de dofter som parningsvilliga mygghonor har. Spindeln lockar till sig mygghanar som blir uppätna när de kommer för att para sig.

Den här spindeln liknar blomman den sitter på, för att lura pollinerande insekter att komma nära. Spindeln äter då upp insekten.

Bild: Ton-Rulkens-CC-BY-SA

En liten fisk som använder både sitt utseende och rörelsemönster för att likna en putsarfisk. Men istället för att putsa andra fiskar som kommer nära, tar den ett bett från dem!

Bild: Jenny-Huang-CC-BY

Gökägg i andra fåglars bon

Det finns arter som parasiterar på en annan art genom att lägga ägg i deras bon. Antingen för att låta den andra arten föda upp deras ungar eller för att den andra arten blir föda åt de egna nykläckta ungarna. Det är också en form av aggressiv mimikry.

Gökfåglar lägger sina ägg i andra fåglars bon. Gökäggen år ganska små och påminner om de andra fåglarnas ägg. När gökungen kläcks knuffar den ut de andra ungarna och blir ensam kvar i boet. Där får den all mat den behöver – från den andra artens fågelföräldrar.

Bild: Per-Harald-Olsen-CC-BY-SA

Campbells mjölksnok

Lampropeltis triangulum cambelli

Härmar den farliga korallormen

Campbells mjölksnok är en orm som är helt ofarlig för människor. Den har varken gift eller huggtänder, istället kramar den ihjäl sitt byte när den hittat ett. Men någon som inte är så van, människa eller djur, kan blanda ihop mjölksnoken med en annan, betydligt farligare orm. Mjölksnoken liknar nämligen det mycket farliga korallormen i färg och mönster. Att härma ett farligt djur för att lura rovdjur att man är farliga att äta, kallas för mimikry.

Mjölksnoken är helt ofarlig, men ändå slår människor ihjäl många mjölksnokar av rädsla varje år. Det beror på att den har en färgteckning som är förvillande lik...

Bild: Johanna-Rylander-Malmö-Museer

...färgteckningen hos flera arter av giftiga korallormar, som till exempel Browns korallorm på bilden.

Bild: Daniel-Pineda-Vera-CC-BY

Troddes tjuvmjölka kor på natten

Mjölksnoken har fått sitt namn från en gammal skröna. Skrönan säger att mjölksnokar tog sig in i ladugårdar på nätterna, för att tjuvmjölka korna. Det här stämmer så klart inte. Något som är mer troligt är att ormarna lockats till gårdar på grund av den stora mängden små gnagare, som gärna håller sig vid bondgårdar.

Bild: Johanna-Rylander-Malmö-Museer

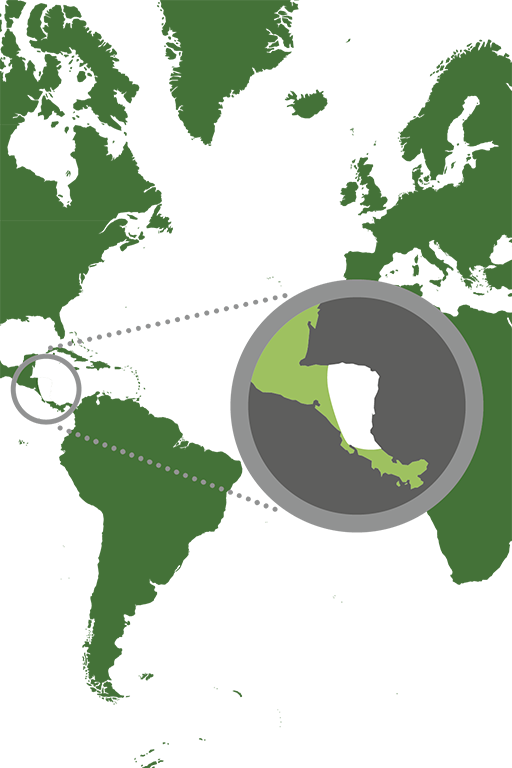

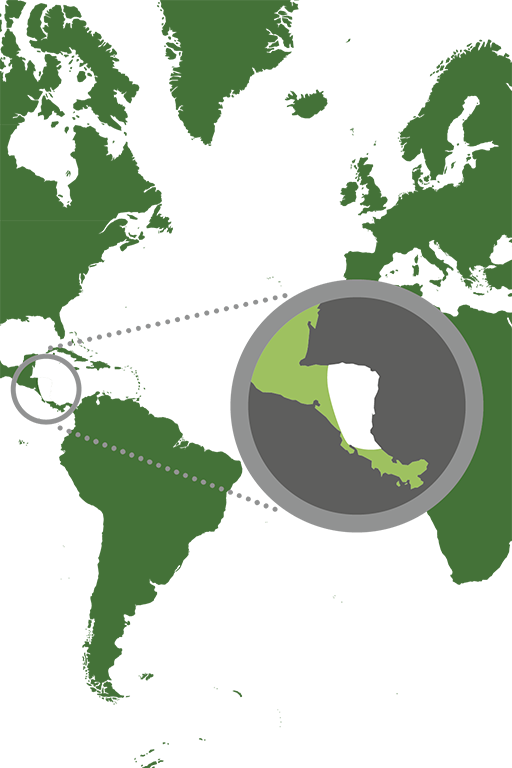

Utbredningsområde i världen

Södra Mexico.

Vit markering = Utbredningsområde

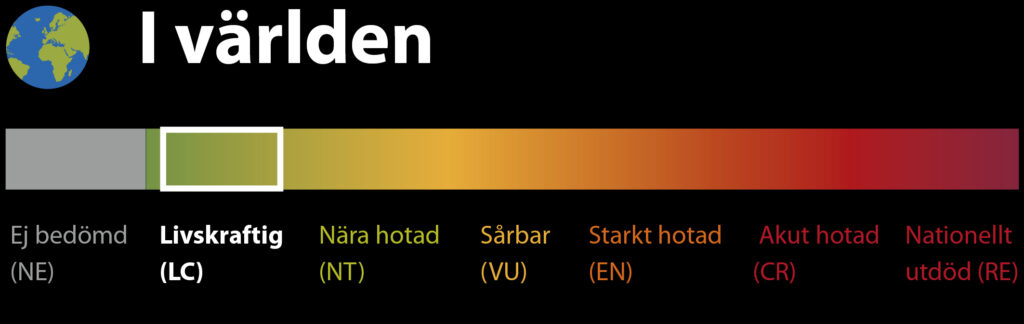

Hotstatus enligt Rödlistan

Reglerad inom handel

CITES: Ej listad.

Vad är Rödlistan?

Rödlistning är ett sätt att bedöma om olika djur- och växtarter är utrotningshotade utifrån kriterier som hur många djur eller växter som finns av arten och hur utbredda de är. En nationell rödlistning bedömer artens risk att dö ut inom ett lands gränser. Den internationella rödlistningen bedömer artens risk att dö ut över hela jorden.

Läs mer

Om rödlistning i Sverige: Artdatabanken, www.artdatabanken.se

Om rödlistning i världen: International Union for Conservation of Nature, IUCN, www.iucn.org

Vad är CITES?

För att bekämpa olaglig handel med djur och växter finns en internationell överenskommelse om handel, som heter CITES. CITES innebär att utrotningshotade djur och växter inte får köpas eller säljas mellan olika länder utan tillstånd.

CITES klassar olika arter i olika kategorier (som kallas Appendix I, II och III) beroende på hur hotad arten är. Ju större hotet från handeln är desto högre skydd. Inom EU finns ytterligare skydd för arter i CITES. EU:s egen klassning har fyra steg: A-D.

Bild: Steve-Hillebrand

Förbjudet att handla med viltfångade arter

Högst skydd mot handel har de arter som är inom kategori A och B. Här gäller oftast att handel mellan EU och övriga världen är förbjuden utan tillstånd. Arter som är CITES A eller B-klassade får inte heller köpas eller säljas inom EU om det inte kan bevisas att de har lagligt ursprung och inte fångats i det vilda.

Att använda växter eller djur för att tillverka souvenirer och annat är också förbjudet. Den som bryter mot reglerna kan dömas till böter eller fängelse.

Kontrollera spridning av arter

Arter som är CITES C-klassade är utrotningshotade i ett visst land men inte nödvändigtvis i hela världen. CITES D-klassning betyder att en art importeras i så stort antal att de behöver regleras för att inte riskera att sprida sig okontrollerat där de inte hör hemma.

What is mimicry?

In nature, competition for living space is fierce and the dangers are many. To protect themselves, animals and plants sometimes use what is known as mimicry. This means that they mimic the appearance or behaviour of dangerous, venomous or poisonous species to scare off predators and avoid being eaten.

Mimicry is common in nature and can occur in many different ways. There are two types of mimicry, called ”defensive” and ”aggressive”. Defensive mimicry is about protecting the animal from being eaten. Aggressive mimicry is more unusual, and involves mimicking something harmless to get closer to prey.

Different sorts of hoverflies, all looking like bees or wasps.

Photo: Alvesgaspar-CC-BY-SA

A hoverfly mimicking a bumblebee.

Photo: Bruce-Marlin-CC-BY-SA

This hoverfly not only mimics a wasp with its colours, but also uses its front legs to imitate a wasp's antennae.

Photo: Bruce-Marlin-CC-BY-SA

This photo shows a common wasp. It has thick antennae which hoverflies lack, but some hoverflies mimic with their front legs.

Photo: Bruce-Marlin-CC-BY-SA

Hover flies resemble wasps

An example of defensive mimicry can be seen in the hover fly. The hover fly is a common insect in Sweden and there are many different kinds of hover flies. While a harmless nectar- and pollen-eating insect, the hover fly mimics the appearance of the venomous and dangerous wasp to deceive predators that might otherwise eat them. The black and yellow stripes of the hover fly resemble those of the wasp with the same colours. Some hover flies are a little hairier and look more like bumblebees.

The milk snake, which lives in North and South America, mimics the appearance of venomous coral snakes to escape enemies. But mimicking another species too well can be dangerous and counterproductive. Sometimes people kill both milk snakes and hover flies because they resemble the dangerous originals.

The milk snake is harmless to people, yet humans kill many milk snakes out of fear every year. That's because it closely resembles...

Photo: Johanna-Rylander-Malmö-Museer

...the colours of multiple venomous species of coral snakes, like this Brown's coral snake.

Photo: Daniel-Pineda-Vera-CC-BY

The mimic octopus is a species able to mimic many different dangerous sea animals, like lionfish, sea snakes and venomous rays.

Photo: Silke-Baron-CC-BY

Spiders with scent like mosquitoes

Aggressive mimicry can also look different. Predators may mimic their prey to get closer to their prey. There are spiders that release scents (pheromones) that mimic the scents of female mosquitoes that are ready to mate. The spider attracts male mosquitoes, which are eaten when they come to mate.

This spider mimics the flower it sits on, to trick pollinating insects into coming close. The spider then eats the insect.

Photo: Ton-Rulkens-CC-BY-SA

A small fish that uses both its colours and movement to mimic a cleaner fish. But instead of grooming fish that come close, it takes a small bite of the fish!

Photo: Jenny-Huang-CC-BY

Cuckoo eggs in nests of other birds

There are species that parasitise another species by laying eggs in their nests. Either to let the other species raise their young or to let the other species become food for their own newly hatched young. This is another form of aggressive mimicry.

Cuckoos lay their eggs in the nests of other birds. Cuckoo eggs are quite small and resemble the eggs of other birds. When the cuckoo chick hatches, it pushes the other chicks out and is left alone in the nest. There it gets all the food it needs – from the bird parents of the other species.

Photo: Per-Harald-Olsen-CC-BY-SA

Campbell’s milk snake

Lampropeltis triangulum cambelli

Mimics the dangerous coral snake

Campbell’s milk snake is a snake that is completely harmless to humans. It has neither venom nor fangs, instead it squeezes its prey to death. But someone not familiar with it, human or animal, can confuse Campbell’s milk snake with another, far more dangerous snake. This is because Campbell’s milk snake resembles the very dangerous coral snake in colour and pattern. Mimicking a dangerous animal to trick predators into thinking you’re dangerous to eat is called mimicry.

The milk snake is harmless to people, yet humans kill many milk snakes out of fear every year. That's because it closely resembles...

Photo: Johanna-Rylander-Malmö-Museer

...the colours of multiple venomous species of coral snakes, like this Brown's coral snake.

Photo: Daniel-Pineda-Vera-CC-BY

Was believed to be milking cows at night

The milk snake gets its name from an old wives’ tale. The story tells that milk snakes used to enter barns at night to steal milk from cows. Of course, this is not true. What is more likely is that the snakes were attracted to farms because of the abundance of small rodents, which are fond of staying around farms.

Photo: Johanna-Rylander-Malmö-Museer

Distribution worldwide

Southern

White marking = Distribution

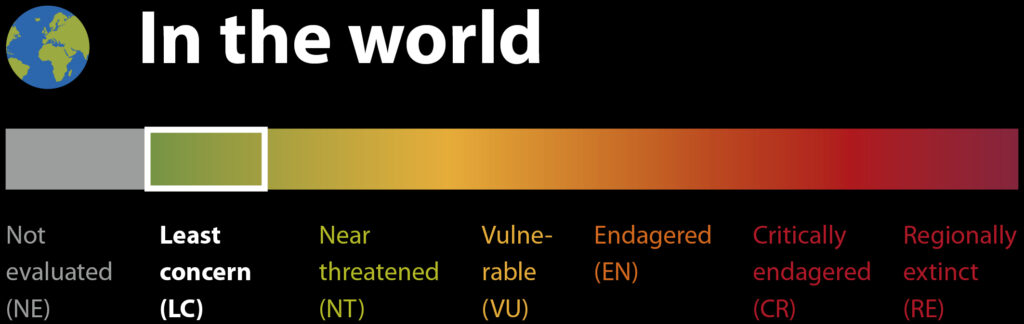

Threat based on the Red List

Trade regulations

CITES: Not listed.

What is the Red List?

The Red List is a way to assess whether different animal and plant species are at risk of extinction based on criteria such as how many animals or plants of a species exist and how widely distributed they are. A national Red List assesses a species’ risk of dying out within national borders. The international Red List assesses a species’ risk of dying out worldwide.

Read more

About the Red List in Sweden: The Swedish Species Information Centre (Artdatabanken), www.artdatabanken.se/en/

About the Red List worldwide: The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), www.iucn.org

What is CITES?

CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) is a treaty that makes it illegal to buy or sell animals and plants that are at risk of extinction between countries without a permit.

CITES classifies species into different categories (called Appendix I, II and III) depending on how endangered each species is. In addition, the more the species is threatened by international trade, the higher its level of protection. Within the EU, CITES-listed species are further classified and protected by the EU’s own classification system. This has four Annexes, from A to D.

Photo: Steve-Hillebrand

Ban on trading wild-caught species

The highest protection against trade is given to CITES-listed species included in the EU’s Annexes A and B. Usually this means that trade between the EU and the rest of the world is illegal without a permit. There is also a ban on trading these species within the EU unless it can be proved that they have a lawful origin and were not caught in the wild.

It is also forbidden to use plants or animals to make souvenirs etc. Anyone who breaks these regulations can be fined or imprisoned.

Controlling the spread of species

CITES-listed species that are in the EU’s Annex C are classified as endangered in at least one country but not necessarily in the whole world. An Annex D classification means that individual members of a species may be imported to the extent that they do not need to be regulated to avoid any risk of them spreading uncontrollably where they do not belong.