Olika som blir lika

För att en art ska kunna överleva måste den kunna anpassa sig till sin omgivning och fortplanta sig. Många arter specialiserar sig till en viss livsmiljö. De hittar sin egen nisch i naturen. Detta kallas för evolution eller utveckling. När arter som inte är släkt med varandra utvecklar liknande beteenden och utseende kallas det för konvergent evolution. De olika arterna lever i samma klimat och miljö – fast i skilda delar av världen. Vilka djur kan du komma på som liknar varandra utan att vara släkt?

Flygekorren lever från östra delarna av Finlande genom hela asiatiska taigan till Korea och Japan. Den lever i skogen och använder sina hudflikar till att glidflyga upp till 50 meter mellan trädtoppar och grenar.

Flygpungekorrar är pungdjur som liknar flygekorrar både till utseende och levnadssätt. Men de är inte särskilt nära släkt. Flygpungekorrarna lever i Australien, och har utvecklat förmågan att glidflyga mellan träden, helt oberoende av flygekorrarna.

Bild: David-Cook-CC-BY-NC

Vingar har utvecklats flera gånger genom historien, hos olika artgrupper som inte är släkt med varandra. Fladdermöss, fåglar och insekter har alla vingar, som uppstått oberoende av varandra.

Flygpungekorre och flygekorre

Den australiensiska flygpungekorren Petaurus breviceps, är ett pungdjur som kan glidflyga tack vare utsträckbara hudflikar mellan fram- och bakben. Den är mycket lik flygekorren, ett moderkaksdäggdjur som lever i andra delar av världen. Arterna har liknande utseende och flygförmåga, men är inte närmare släkt. De har anpassat sig till samma miljö och fått nästan samma utseende.

De äldsta fynden av hajar är ungefär 420 miljoner år gamla. Hajar är väl anpassade till att simma snabbt och tyst genom vattnet, med sin strömlinjeformade kropp.

Bild: Kakidai-CC-BY-SA

Delfinernas förfäder blev vattenlevande för omkring 40 miljoner år sedan - de har alltså funnits mycket kortare tid än hajarna. Delfinerna är däggdjur, som utvecklat en liknande kropp och ett liknande levnadssätt som hajen, utan att vara släkt.

Bild: sheilapic76-CC-BY

Däggdjuret delfin och fisken haj

Delfiner och hajar är också exempel på konvergent evolution. Delfinen är ett däggdjur vars föregångare levde på land. Med tiden anpassade den sig till ett liv i vatten. Delfinen fick en lång strömlinjeformad kropp. Den har en stark stjärtfena och styrfenor på sidorna och ovandelen av kroppen för att kunna ta sig fram snabbt och smidigt i vattnet. Hajarna har en liknade kroppsform men är en broskfisk. Kroppen hålls upp av brosk, och hajen andas med gälar under vattnet. Delfiner har ett skelett av ben, och andas in luft vid ytan. Trots dessa skillnader är de väldigt lika varandra, och delar samma nisch i naturen.

Kungsboan kramar ihjäl sina byten och sväljer dem hela. Boaormar lever i Sydamerika och föder levande ungar, men förutom det är de väldigt lika pytonormar som lever i Asien. De liknande utseendena och levnadssätten har utvecklats oberoende av varandra.

Kungspytonormen lever i Afrika och många andra pytonormar lever i Asien. De har liknande levnadssätt och utseende som boaormar, men lägger ägg som de ruvar. Likheterna mellan boaormar och pytonormar är ett exempel på konvergent evolution.

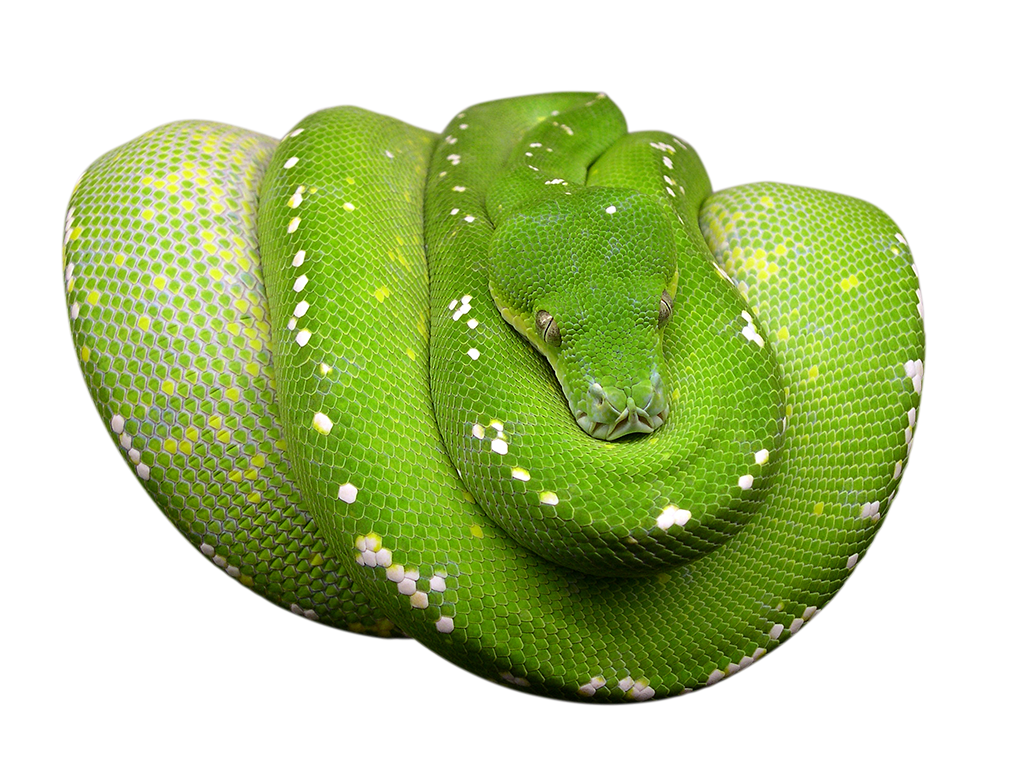

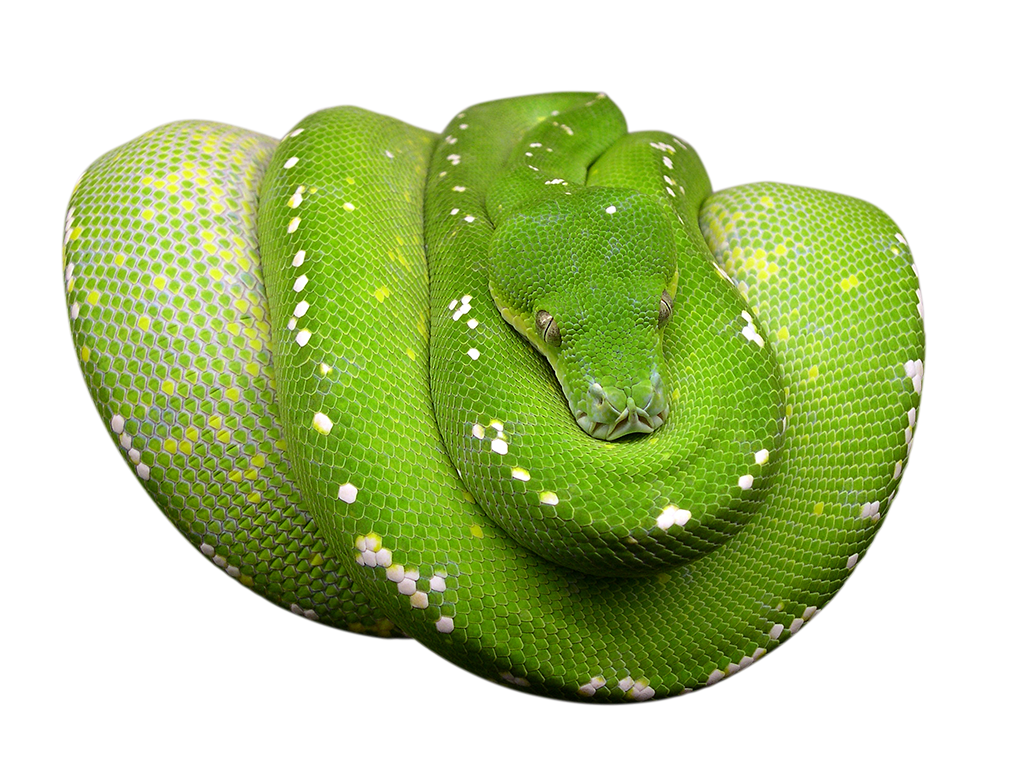

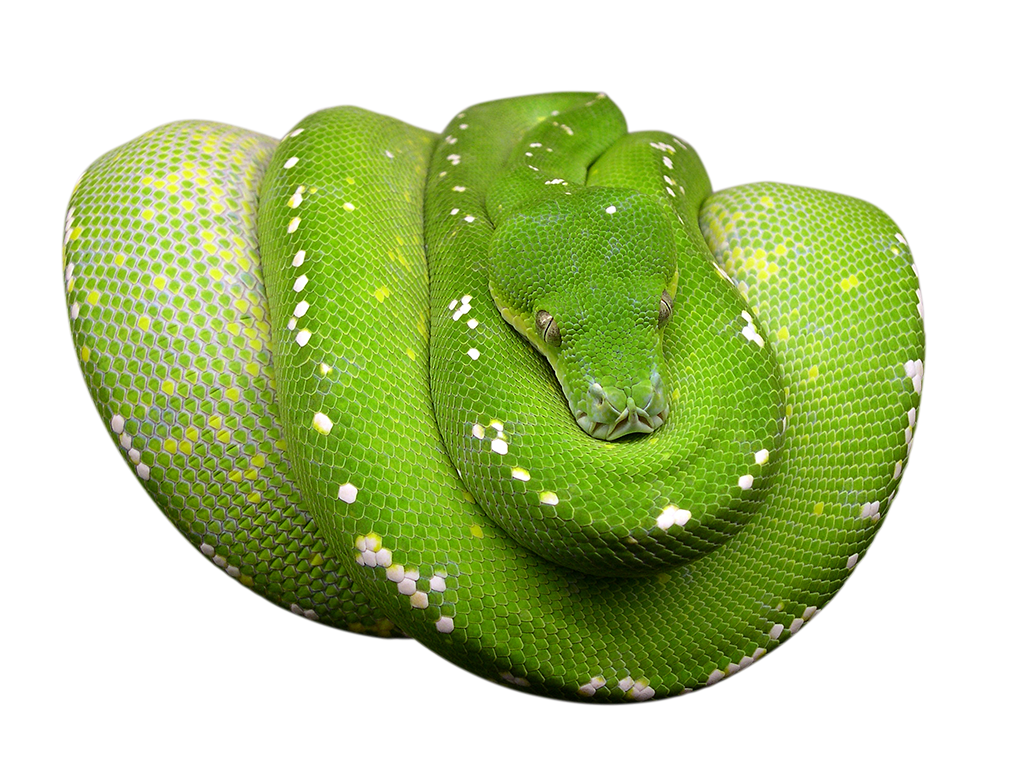

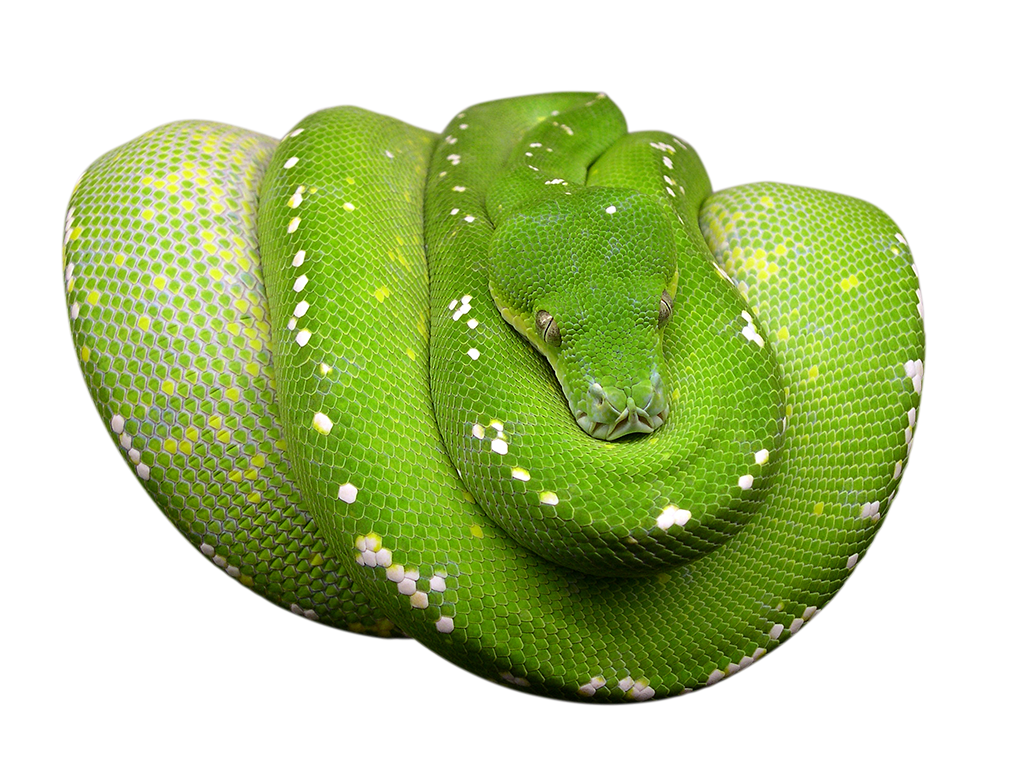

Smaragdboan är en boaorm som lever i de tropiska delarna av Sydamerika. Den är mycket lik grön trädpytonorm.

Bild: Joseph-Bylund-CC-BY-SA

Grön trädpyton lever i Sydostasien och Nya Guinea. Den har många likheter med smaragdboa, men inget nära släktskap.

Bild: Jesper-Flygare-Malmö-Museer

Fossan är ett rovdjur som lever på Madagaskar. Kroppen och levnadssättet liknar kattdjurens, men de är inte närmare släkt.

Bild: Rod-Waddington-CC-BY-SA

Jaguarundin är ett litet kattdjur som liknar madagaskarrovdjuret fossa, utan att de är släkt.

Bild: Rod-Waddington-CC-BY-SA

Boaorm och pytonorm – lika men olika

Boaormen och pytonormen är också exempel på konvergent evolution. Det är mer än 60 miljoner år sedan de hade en gemensam anfader, och är inte nära släkt med varandra. Trots detta är de väldigt lika. De har levt i samma naturliga nisch under lång tid och anpassat sig till klimatet och miljön.

Fossan som liknar en katt

Rovdjuret fossa som lever på Madagaskar påminner till utseendet om en katt. Fossan har flexibla fotleder och är bra på att klättra i träd och hoppa precis som en katt. Men de är inte närmare släkt med varandra. Fossan tillhör en helt egen familj av rovdjur – som bara lever på Madagaskar.

Trilobiterna var bland de första djuren på jorden som hade en bra syn. De utvecklades redan för en halv miljard år sedan. Ögonen liknar de som kräftdjur och insekter har idag.

Bläckfiskar tillhör blötdjuren, och har avancerade ögon med näthinna, hornhinna och lins - precis som hos ryggradsdjuren. Ögonen har dock utvecklats genom konvergent evolution - helt oberoende av varandra.

Bild: Laszlo-Ilyes-CC-BY

Ryggradsdjurens ögon utvecklades från hjärnceller, medan blötdjurens ögon utvecklades från hudceller. Ändå har de fått väldigt lika form och funktion.

Bild: Pathogenhk-CC-BY-SA

Ögat har utvecklats många gånger

Ett annat exempel på konvergent evolution är ögats utveckling hos olika arter. Forskare anser att ögat utvecklats många, av varandra oberoende, gånger sedan livet uppstod på jorden. De tidigaste exemplen på ögats utveckling finns redan för mer än 500 miljoner år sedan hos trilobiterna som levde i haven. Många, nu levande, arter har ögon som fungerar på liknande sätt. Däggdjur, bläckfiskar och fiskar har ögon med näthinna, lins och hornhinna.

Grön trädpyton

Morelia viridis

Kan ”se” värme

Högt upp bland löv och grenar i regnskogsträd i området kring Nya Guinea och norra Australien, ligger den gröna trädpytonormen ihopringlad på en gren. Med sin knallgröna färg är den perfekt kamouflerad bland löven. På dagen vilar den mest, men på natten är den beredd att blixtsnabbt attackera ett byte. Längs med munnen har ormen hål som kallas ”värmegropar”. Dessa gör att den gröna trädpytonormen kan ”se” värme – och på så sätt känna av om något levande bytesdjur finns i närheten. När ormen fått tag på ett byte, använder den sina starka muskler för att krama ihjäl det, innan den sväljer bytet helt – med huvudet före. Den gröna trädpytonormen är inte giftig alls, men har långa tänder som den använder för att få fatt i sitt byte.

Ruvar och värmer sina ägg

Största delen av livet lever gröna trädpytonormar för sig själva, men inte när det är dags för parning. Själva parningen har aldrig lyckats studeras i det vilda, men i fångenskap vet man att honan och hanen slingrar sig runt varandra i något som liknar en stående dans. Efter parningen lägger honan ägg – som hon sedan vaktar tills de kläcks. Hon ruvar och värmer äggen genom att göra skakande rörelser.

När ungarna kläcks, har de inte samma knallgröna färg som sina föräldrar. I stället är de oftast knallgula eller orangea, färger som är ett bättre kamouflage mot regnskogens marknivå – där ungarna spenderar sin första tid i livet. Allt eftersom de blir äldre och större, flyttar de högre upp i trädkronorna, och kroppsfärgen ändras också i takt med det. Det gröna trädpytonormen räknas idag inte som utrotningshotad enligt Rödlistan, men eftersom arten lever i regnskogen – finns det en risk att den kommer hotas i takt med att skogarna försvinner.

Bild: Anders-Zimny

Lockar med svanstippen

Den gröna trädpytonormen jagar oftast med hjälp av sina värmegropar, och att vänta på ett byte. Men ibland kan den också använda sin svanstipp som lockbete! Svanstippen är liten, smal och mörk, och kan likna en liten larv eller mask när ormen vickar på den. Då kan det hända att ett nyfiket djur kommer nära – för att sedan blixtsnabbt fångas av ormen.

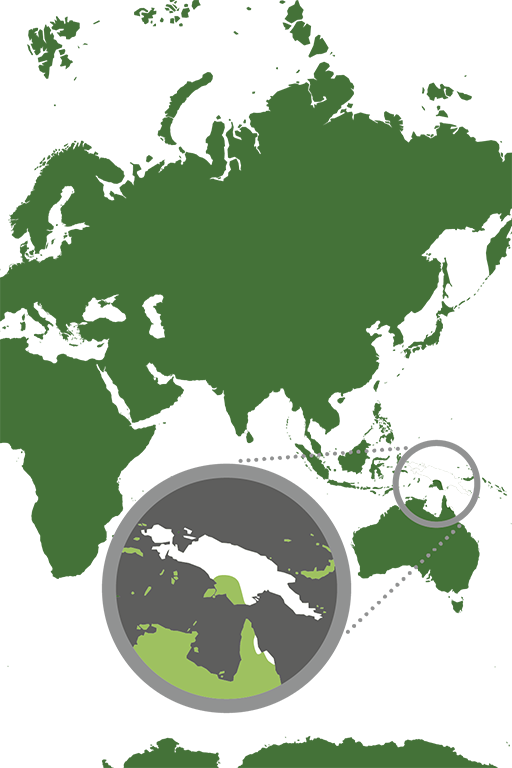

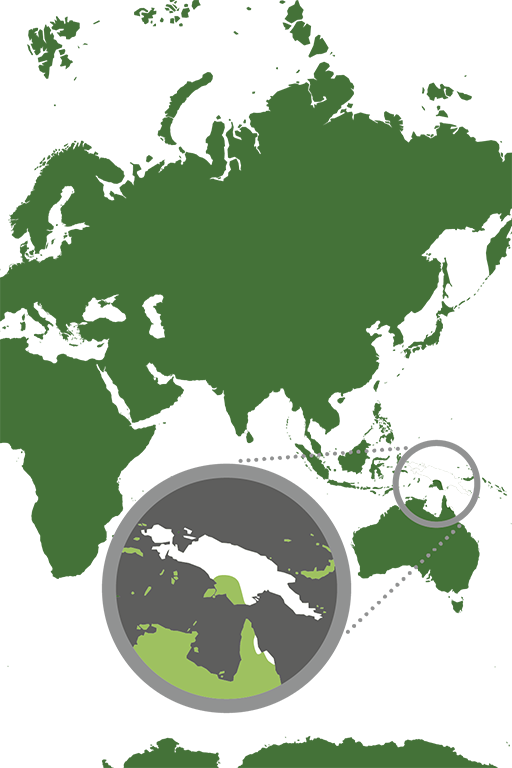

Utbredningsområde i världen

Nya Guinea, Indonesien och norra Australien.

Vit markering = Utbredningsområde.

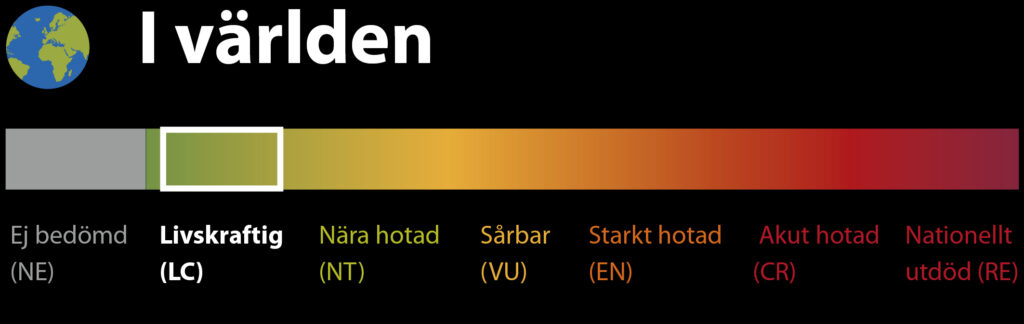

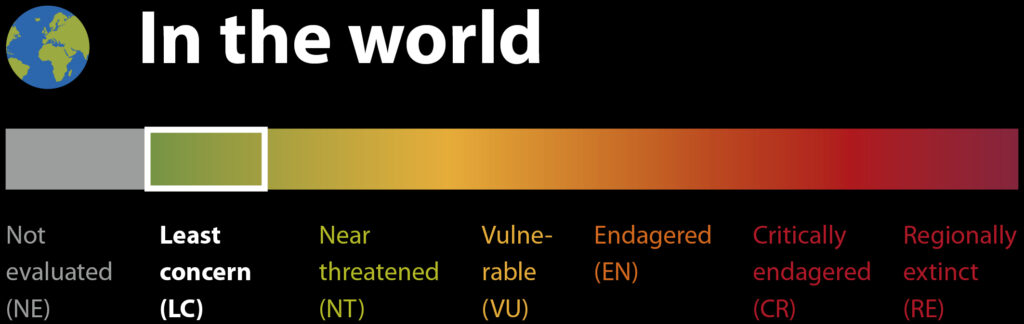

Hotstatus enligt Rödlistan

Reglerad inom handel

CITES: B-listad.

Vad är Rödlistan?

Rödlistning är ett sätt att bedöma om olika djur- och växtarter är utrotningshotade utifrån kriterier som hur många djur eller växter som finns av arten och hur utbredda de är. En nationell rödlistning bedömer artens risk att dö ut inom ett lands gränser. Den internationella rödlistningen bedömer artens risk att dö ut över hela jorden.

Läs mer

Om rödlistning i Sverige: Artdatabanken, www.artdatabanken.se

Om rödlistning i världen: International Union for Conservation of Nature, IUCN, www.iucn.org

Vad är CITES?

För att bekämpa olaglig handel med djur och växter finns en internationell överenskommelse om handel, som heter CITES. CITES innebär att utrotningshotade djur och växter inte får köpas eller säljas mellan olika länder utan tillstånd.

CITES klassar olika arter i olika kategorier (som kallas Appendix I, II och III) beroende på hur hotad arten är. Ju större hotet från handeln är desto högre skydd. Inom EU finns ytterligare skydd för arter i CITES. EU:s egen klassning har fyra steg: A-D.

Bild: Steve-Hillebrand

Förbjudet att handla med viltfångade arter

Högst skydd mot handel har de arter som är inom kategori A och B. Här gäller oftast att handel mellan EU och övriga världen är förbjuden utan tillstånd. Arter som är CITES A eller B-klassade får inte heller köpas eller säljas inom EU om det inte kan bevisas att de har lagligt ursprung och inte fångats i det vilda.

Att använda växter eller djur för att tillverka souvenirer och annat är också förbjudet. Den som bryter mot reglerna kan dömas till böter eller fängelse.

Kontrollera spridning av arter

Arter som är CITES C-klassade är utrotningshotade i ett visst land men inte nödvändigtvis i hela världen. CITES D-klassning betyder att en art importeras i så stort antal att de behöver regleras för att inte riskera att sprida sig okontrollerat där de inte hör hemma.

Different but becoming similar

For a species to survive, it must be able to adapt to its environment and reproduce. Many species specialise in a particular habitat. They find their own niche in nature. This is called evolution or development. When unrelated species develop similar behaviours and appearance, it is called convergent evolution. The different species live in the same climate and environment – but in different parts of the world. What animals can you think of that are similar but not related?

The Siberian flying squirrel lives from the eastern parts of Finland all the way through the Asian taiga to Korea and Japan. It lives in the forest, and uses its skin flaps to glide up to 50 meters between treetops and branches.

The flying phalangers such as the sugar glider, are marsupials that resemble flying squirrels both in apperence and way of living. But they are not closely related. The sugar glider lives in Australia, and has developed the ability to glide completely separate from the flying squirrels.

Photo: David-Cook-CC-BY-NC

Wings has evolved many times through history, in different groups of species unrelated to eachother. Bats, birds and insects all have wings, that have evolved independantly.

Gliders and flying squirrels

The sugar glider, Petaurus breviceps, is a marsupial native to Australia, that can glide thanks to extendable skin flaps between its front and back legs. It is very similar to the flying squirrel, a placental mammal that lives in other parts of the world. The species have a similar appearance and flying ability, but are not closely related. They have adapted to a similar environment and have almost the same appearance.

The oldest shark finds are about 420 million years old. Sharks are well adapted to swimming quickly and silently through the water, with their streamlined bodies.

Photo: Kakidai-CC-BY-SA

The ancient relatives of dolphins became water-living arond 40 million years ago - meaning they have existed much shorter than sharks. Dolphins are mammals, that have gotten a similar body and way of living as the sharks - without being related.

Photo: sheilapic76-CC-BY

Dolphins are mammals and sharks are fish

Dolphins and sharks are also examples of convergent evolution. The dolphin is a mammal whose predecessor lived on land. Over time, it adapted to life in the water. The dolphin developed a long, streamlined body. It has a powerful tail fin and fins on the sides and top of its body that allow it to move quickly and smoothly through the water. Sharks have a similar body shape but are a cartilaginous fish. The body is held up by cartilage, and the shark breathes with gills beneath the water. Dolphins have a skeleton of bones, and breathe air at the surface. Despite these differences, they are very similar, and share the same niche in nature.

The boa constrictor squeezes its prey to death and swallows it whole. Boas live in South America and give birth to live young, but apart from that, they are very similar to pythons living in Asia. The similarities in appearance and ways of living have developed independant of eachother.

The royal python lives in Africa, and many other pythons live in Asia. They have a similar way of living and appearance as boas, but they lay eggs which they incubate. The similarities between boas and pythons are examples of convergent evolution.

The emerald boa is a boa living in the tropical parts of South America. It is very similar to the green tree python.

Photo: Joseph-Bylund-CC-BY-SA

The green tree python lives in Southeast Asia and New Guinea. It has many similarities with the emerald boa, but the species are not closely related.

Photo: Jesper-Flygare-Malmö-Museer

The fossa is predator living in Madagascar. Its body and way of living is similar to cats, but they are not closely related.

Photo: Rod-Waddington-CC-BY-SA

The jaguarundin is a small wild cat, that resembles the madagascan predator fossa, without being closely related.

Photo: Rod-Waddington-CC-BY-SA

Boas and pythons – similar but different

The boa and the python are also examples of convergent evolution. They shared a common ancestor more than 60 million years ago, and are not closely related. Nevertheless, they are very similar. They have lived in the same natural niche for a long time, adapting to the climate and environment.

The fossa that looks like a cat

The predator known as the fossa, which lives in Madagascar, resembles a cat in appearance. The fossa has flexible ankles and is a good tree climber and can jump just as well as a cat. But they are not closely related. The fossa belongs to a unique family of predators – only found in Madagascar.

The trilobites were among the first animals on Earth with good eyesight. The eyes evolved about half a billion years ago! The trilobites' eyes are similar to those of today's crustaceans and insects.

The cephalopods, such as octopuses, belong to the molluscs. Cephalopods have advanced eyes, with retina, cornea and lens - just like vertebrates have. However, the eyes have evolved through convergent evolution - completely independently of each other.

Photo: Laszlo-Ilyes-CC-BY

Vertebrates' eyes developed from brain cells, while the molluscs' eyes developed from skin cells. Yet, they have gotten very similar shapes and functions.

Photo: Pathogenhk-CC-BY-SA

The eye has evolved many times

Another example of convergent evolution is the evolution of the eye in different species. Scientists believe that the eye has evolved many independent times since life first appeared on Earth. The earliest examples of eye evolution date back more than 500 million years to the trilobites that lived in the oceans. Many species alive today have eyes that function in a similar way. Mammals, cephalopods (such octopuses) and fish have eyes with a retina, lens and cornea.

Green Tree Python

Morelia viridis

Can “see” heat

High up among the leaves and branches of rainforest trees in the area of New Guinea and northern Australia, the green tree python lies coiled up on a branch. With its bright green colour, it is perfectly camouflaged among the leaves. During the day it rests most of the time, but at night it is ready to attack prey at lightning speed. Along its mouth, the snake has holes called “heat pits”. These allow the green tree python to “see” heat – and thereby sense if any living prey is nearby. Once the snake has caught its prey, it uses its strong muscles to suffocate it, before swallowing the prey whole—head first. The green tree python is not venomous at all, but has long teeth that it uses to catch its prey.

Incubating and warming their eggs

For most of their lives, green tree pythons live alone, but not when it is time for mating. The mating itself has never been studied in the wild, but in captivity it is known that the female and the male wrap around each other in something resembling a standing dance. After mating, the female lays eggs – which she then guards until they hatch. She incubates and warms the eggs by making shaking movements.

When the offspring hatch, they do not have the same bright green colour as their parents. Instead, they are usually bright yellow or orange, colours that are a better camouflage against the bottom of the rainforest – where the juvenile snakes spend their first period of life. As they get older and bigger, they move higher up into the canopy, and their body colour also changes with it. The green tree python is not currently considered endangered according to the Red List, but since the species lives in the rainforest – there is a risk that it will be endangered as the forests disappear.

Photo: Anders-Zimny

Attracting prey with the tip of the tail

The green tree python usually hunts with the help of its heat pits, and waits for its prey. But sometimes it can also use the tip of its tail as a decoy! The tip of the tail is small, narrow and dark, and can resemble a small larva or worm when the snake wiggles it. Then a curious animal might come close – only to be caught by the snake in a flash.

Distribution worldwide

New Guinea, Indonesia and Northern Australia

Whit marking = Distribution

Threat based on the Red List

Trade regulations

CITES: B-listed.

What is the Red List?

The Red List is a way to assess whether different animal and plant species are at risk of extinction based on criteria such as how many animals or plants of a species exist and how widely distributed they are. A national Red List assesses a species’ risk of dying out within national borders. The international Red List assesses a species’ risk of dying out worldwide.

Read more

About the Red List in Sweden: The Swedish Species Information Centre (Artdatabanken), www.artdatabanken.se/en/

About the Red List worldwide: The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), www.iucn.org

What is CITES?

CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) is a treaty that makes it illegal to buy or sell animals and plants that are at risk of extinction between countries without a permit.

CITES classifies species into different categories (called Appendix I, II and III) depending on how endangered each species is. In addition, the more the species is threatened by international trade, the higher its level of protection. Within the EU, CITES-listed species are further classified and protected by the EU’s own classification system. This has four Annexes, from A to D.

Photo: Steve-Hillebrand

Ban on trading wild-caught species

The highest protection against trade is given to CITES-listed species included in the EU’s Annexes A and B. Usually this means that trade between the EU and the rest of the world is illegal without a permit. There is also a ban on trading these species within the EU unless it can be proved that they have a lawful origin and were not caught in the wild.

It is also forbidden to use plants or animals to make souvenirs etc. Anyone who breaks these regulations can be fined or imprisoned.

Controlling the spread of species

CITES-listed species that are in the EU’s Annex C are classified as endangered in at least one country but not necessarily in the whole world. An Annex D classification means that individual members of a species may be imported to the extent that they do not need to be regulated to avoid any risk of them spreading uncontrollably where they do not belong.