Olaglig handel med djur

Globalt är handel med djur ett stort miljöproblem. Utrotningshotade djur köps och säljs för att bli husdjur, eller användas som mat, naturmedicin, souvenirer med mera.

En varan som smugglats i en strumpa inuti en högtalare.

Bild: US-Fish-And-Wildlife-Services

Sköldpaddor packade och smugglade i tidningspapper och tejp.

Bild: Bob-Herndon-US-Fish-And-Wildlife-Services

Ormar i strumpbyxor, smugglade inuti en högtalare.

Bild: Bob-Herndon-US-Fish-And-Wildlife-Services

Kungskobra smugglad i en chipsburk.

Bild: US-Fish-And-Wildlife-Services

Reptiler vanliga smuggeldjur

Reptiler är den vanligaste gruppen inom den olagliga handeln med levande djur. Eftersom de flesta reptiler klarar sig bra på väldigt lite mat och vatten, är de tyvärr “praktiska” att smuggla. Det finns många reptilsamlare som är beredda att betala mycket för ovanliga arter av ormar, ödlor och sköldpaddor. När levande djur smugglas är förhållandena för djuren oftast mycket dåliga ur djurskyddssynpunkt.

Skinn och andra produkter från djur, som beslagtagits på JFK-flygplatsen i New York.

Bild: Steve-Hillebrand

Smugglade asiatiska sångfåglar beslagtagna av polisen i Los Angeles.

En tröglori som får tänderna utdragna i samband med smuggling.

Bild: Materialscientist-CC-BY-SA

Ormar och myrkottar utsatta för olaglig handel i Myanmar.

Bild: Dan-Bennett-CC-BY

CITES

För att komma tillrätta med det här problemet finns en internationell överenskommelse som kallas CITES. CITES reglerar hur, och om, arter får köpas och säljas. Om en djurart är listad i CITES betyder det att handel med det djuret är antingen helt olaglig eller kräver tillstånd. Det gäller både levande djur och produkter som innehåller delar av djur. Det kan vara till exempel skinn, ben, ägg eller kött.

TRAFFIC

För att hålla koll på om reglerna i CITES faktiskt följs har Världsnaturfonden WWF och Internationella Naturvårdsunionen IUCN startat en organisation som heter TRAFFIC. De jobbar med att bevaka handeln med djur, att anmäla olaglig handel, att informera om vad som är tillåtet och inte, och att föreslå lagstiftning som kan begränsa smuggling.

Gilaödla

Heloderma suspectum cinctum

Giftig ödla

Det finns tre giftiga ödlor i världen. Den ena ser du framför dig, gilaödlan. De andra är skorpiongiftödla och komodovaran. Gilaödlan injicerar inte giftet i sitt byte. Istället biter den tag och tuggar på bytesdjuret. Under tiden rinner den giftiga saliven ner i såret.

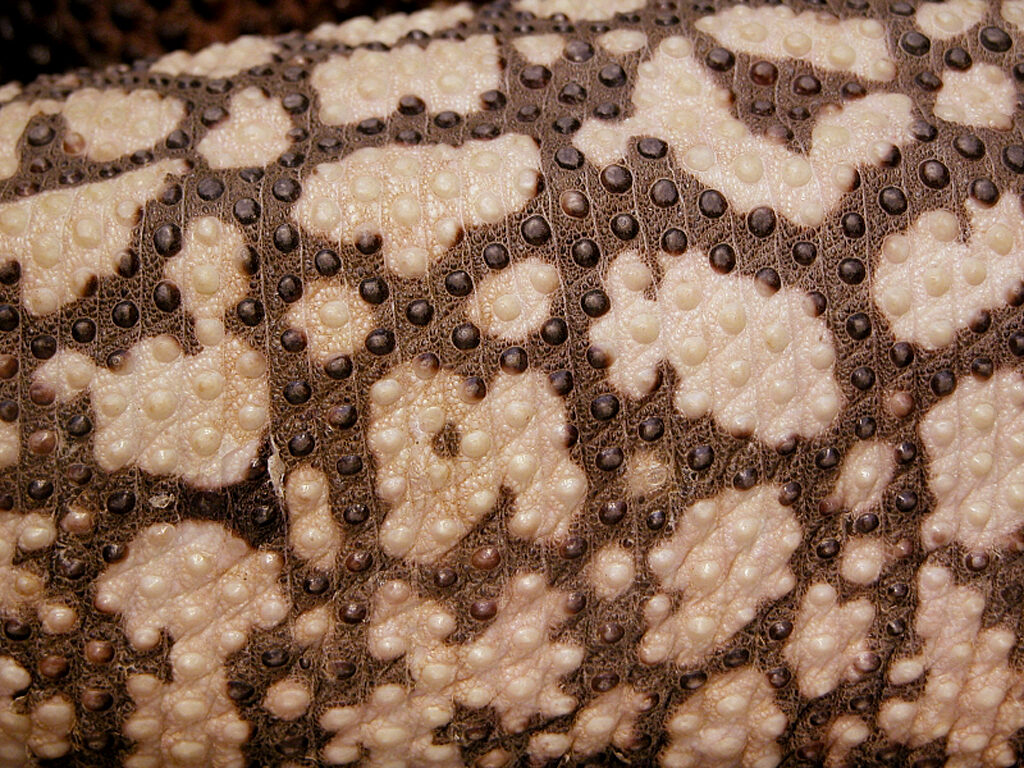

På kroppen har gilaödlan en slags rustning. Det är knölar som skyddar precis som hos varaner.

Bild: Fritz-Geller-Grimm-CC-BY-SA

Lever ensam i öknen

Gilaödlan är en av USAs största ödlor. De lever ensamma och vandrar bara korta sträckor. Under de heta dagarna i öknen ligger den gömd i klippskrevor, under stenar eller i gropar. Men i skymningen och på natten är den aktiv.

På vintern går gilaödlan i dvala. Då äter den inte utan lever på fett som lagrats i den tjocka svansen. Den väger ungefär 1,5 -2,5 kilo.

Bild: SearchNet-Media-CC-BY

Hot mot gilaödlan

Gilaödlan hotas i naturen av att deras livsmiljö blir mindre och mindre. Jordbruk och vägbyggen gör områdena mindre och splittrade från varandra. Ödlorna blir då isolerade från varandra. Ödlan hotas även av illegal insamling för användning som terrariedjur. Men det har minskat i omfattning.

Utbredningsområde i världen

Sydvästra USA

och nordvästra

Mexiko.

Vit markering = Utbredningsområde

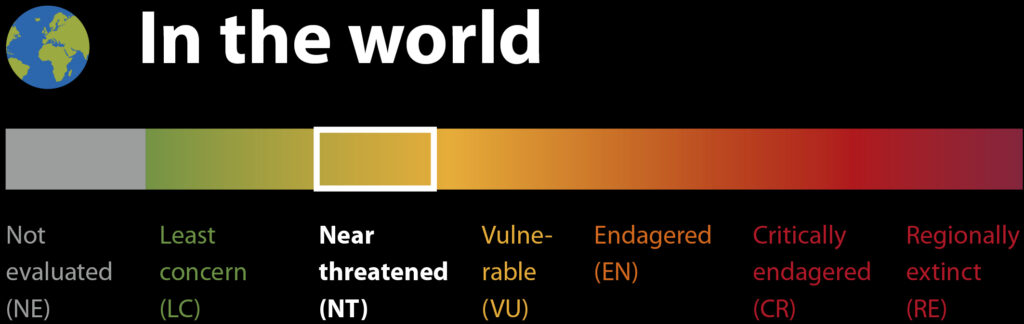

Hotstatus enligt Rödlistan

Reglerad inom handel

CITES: B-listad.

Vad är Rödlistan?

Rödlistning är ett sätt att bedöma om olika djur- och växtarter är utrotningshotade utifrån kriterier som hur många djur eller växter som finns av arten och hur utbredda de är. En nationell rödlistning bedömer artens risk att dö ut inom ett lands gränser. Den internationella rödlistningen bedömer artens risk att dö ut över hela jorden.

Läs mer

Om rödlistning i Sverige: Artdatabanken, www.artdatabanken.se

Om rödlistning i världen: International Union for Conservation of Nature, IUCN, www.iucn.org

Vad är CITES?

För att bekämpa olaglig handel med djur och växter finns en internationell överenskommelse om handel, som heter CITES. CITES innebär att utrotningshotade djur och växter inte får köpas eller säljas mellan olika länder utan tillstånd.

CITES klassar olika arter i olika kategorier (som kallas Appendix I, II och III) beroende på hur hotad arten är. Ju större hotet från handeln är desto högre skydd. Inom EU finns ytterligare skydd för arter i CITES. EU:s egen klassning har fyra steg: A-D.

Bild: Steve-Hillebrand

Förbjudet att handla med viltfångade arter

Högst skydd mot handel har de arter som är inom kategori A och B. Här gäller oftast att handel mellan EU och övriga världen är förbjuden utan tillstånd. Arter som är CITES A eller B-klassade får inte heller köpas eller säljas inom EU om det inte kan bevisas att de har lagligt ursprung och inte fångats i det vilda.

Att använda växter eller djur för att tillverka souvenirer och annat är också förbjudet. Den som bryter mot reglerna kan dömas till böter eller fängelse.

Kontrollera spridning av arter

Arter som är CITES C-klassade är utrotningshotade i ett visst land men inte nödvändigtvis i hela världen. CITES D-klassning betyder att en art importeras i så stort antal att de behöver regleras för att inte riskera att sprida sig okontrollerat där de inte hör hemma.

Illegal animal trade

Globally, trade in animals is a major environmental problem. Species at risk of extinction are being bought and sold to become pets or used as food, natural medicine, souvenirs etc.

A monitor lizard smuggled in a sock inside a speaker.

Photo: US-Fish-And-Wildlife-Services

Turtles packed and smuggled in newspaper and tape.

Photo: Bob-Herndon-US-Fish-And-Wildlife-Services

Snakes in pantihose, smuggled inside a speaker.

Photo: Bob-Herndon-US-Fish-And-Wildlife-Services

A king cobra smuggled inside a jar of chips.

Photo: US-Fish-And-Wildlife-Services

Reptiles are often smuggled

Reptiles are the most common group of species involved in the illegal trade of live animals. Because most reptiles can cope well on very little food and water, they are unfortunately “practical” to smuggle. Many reptile collectors are prepared to pay a lot for unusual species of snakes, lizards and turtles. When live animals are smuggled, the conditions for them are often very poor from an animal welfare perspective.

Pelts and other animal origin products confiscated on the JFK Airport in New York.

Photo: Steve-Hillebrand

Smuggled asian songbirds confiscated by the Los Angeles police.

A slow lori getting its teeth pulled in connection to smuggling.

Photo: Materialscientist-CC-BY-SA

Snakes and pangolins exposed to illegal animal trade in Myanmar.

Photo: Dan-Bennett-CC-BY

CITES

To try to deal with this problem, there is an international treaty called CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora). It regulates how and whether species can be bought and sold. If a species is listed by CITES, it means that trade in that animal is either completely illegal or requires a permit. This applies both to live animals and to products that contain animal parts, such as skins, bones, eggs or meat.

TRAFFIC

To monitor compliance with CITES regulations, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) founded an organisation called TRAFFIC. It works to monitor trade in animals, to report illegal trade, to inform people what is permitted or not, and to propose legislation that can limit smuggling.

Gila Monster

Heloderma suspectum cinctum

Venomous lizard

There are three venomous lizards in the world. One, you see before you – the Gila monster. The others are the Mexican beaded lizard and the Komodo dragon. The Gila monster does not inject the venom into its prey. Instead, it bites into the prey and chews it. During that time, the lizard’s venomous saliva runs into the wound.

The Gila monster has a kind of armour on its body, consisting of many tiny knobs, which provide protection just like they do on monitor lizards.

Photo: Fritz-Geller-Grimm-CC-BY-SA

Lives alone in the desert

The Gila monster is one of the biggest lizards in the United States. It lives alone and only roams for short distances. During the hot desert days, the lizard lies hidden in rock crevices, underneath stones or in hollows. But it is active at dusk and at night.

The Gila monster hibernates in winter. It does not eat then but instead lives off fat it has stored in its thick tail, which weighs about 1.5 to 2.5 kilos.

Photo: SearchNet-Media-CC-BY

Threats to the Gila monster

In nature, the Gila monster is threatened because its habitat is shrinking more and more. Farming and new road construction are making the habitat zones smaller and cut off from each other. Then the lizards become isolated from each other.

The lizard is also threatened by poaching. Specimens are caught illegally to be used as terrarium animals for, although this is being done less now.

Distribution worldwide

South west

United States

and Mexico.

White marking = Distribution

Threat based on the Red List

Trade regulations

CITES: B-listed.

What is the Red List?

The Red List is a way to assess whether different animal and plant species are at risk of extinction based on criteria such as how many animals or plants of a species exist and how widely distributed they are. A national Red List assesses a species’ risk of dying out within national borders. The international Red List assesses a species’ risk of dying out worldwide.

Read more

About the Red List in Sweden: The Swedish Species Information Centre (Artdatabanken), www.artdatabanken.se/en/

About the Red List worldwide: The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), www.iucn.org

What is CITES?

CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) is a treaty that makes it illegal to buy or sell animals and plants that are at risk of extinction between countries without a permit.

CITES classifies species into different categories (called Appendix I, II and III) depending on how endangered each species is. In addition, the more the species is threatened by international trade, the higher its level of protection. Within the EU, CITES-listed species are further classified and protected by the EU’s own classification system. This has four Annexes, from A to D.

Photo: Steve-Hillebrand

Ban on trading wild-caught species

The highest protection against trade is given to CITES-listed species included in the EU’s Annexes A and B. Usually this means that trade between the EU and the rest of the world is illegal without a permit. There is also a ban on trading these species within the EU unless it can be proved that they have a lawful origin and were not caught in the wild.

It is also forbidden to use plants or animals to make souvenirs etc. Anyone who breaks these regulations can be fined or imprisoned.

Controlling the spread of species

CITES-listed species that are in the EU’s Annex C are classified as endangered in at least one country but not necessarily in the whole world. An Annex D classification means that individual members of a species may be imported to the extent that they do not need to be regulated to avoid any risk of them spreading uncontrollably where they do not belong.